Your heart has 4 chambers=

2 uppers=atriums & 2 lowers=ventricles.

Congenital heart defects:

1. Types of Hole Defects in the heart:

This a problem with your heart that you’re born with.

-They’re the most common kind of birth defect.

There are at least 18 different types of congenital heart defects. Most affect the walls, valves, or blood vessels of your heart. Some are serious and may need several surgeries and treatments.

1-Heart Septal Defects=Hole(s) in the Heart

This means you’re born with a hole in the wall, or septum of the heart that separates the left and right sides of your heart. The hole lets blood from the two sides mix. This allows more oxygenated (L side of the heart) and more carbon dioxide blood (Rt side of the heart) mix together causing many problems.

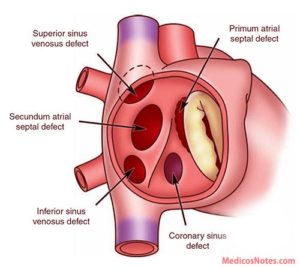

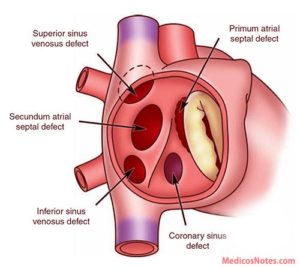

a Atrial Septal Defect (ASD)

An ASD is a hole in the wall between the upper chambers or the right and left atrium, of your heart.

Some ASDs close on their own. Your doctor may need to repair a medium or large ASD with open-heart surgery or another procedure.

The cardiology surgeon might seal the hole with a minimally invasive catheter procedure. The MD inserts a small tube, or catheter, in your blood vessel all the way to your heart. Then he can cover the hole with a variety of devices.

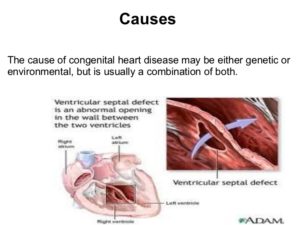

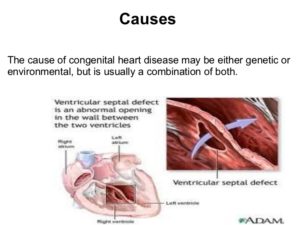

b Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

A ventricular septal defect (pronounced ven·tric·u·lar sep·tal de·fect) (VSD) is a birth defect of the heart in which there is a hole in the wall (septum) that separates the two lower chambers (ventricles) of the heart. This wall also is called the ventricular septum.

A VSD is a hole in the part of your septum that separates your heart’s lower chambers that we call ventricles. If you have a VSD, blood gets pumped back to your lungs instead of to your body.

A small VSD may also close on its own. But if yours is larger, you may need surgery to repair it. Similar to ASD surgery, just a different spot on the chambers.

c Complete Atrioventricular Canal Defect (CAVC)

This is the most serious septal defect. It’s when you have a hole in your heart that affects all four chambers.

Complete atrioventricular canal (CAVC) defect is a severe congenital heart disease in which there is a large hole in the tissue (the septum) that separates the left and right sides of the heart. The hole is in the center of the heart, where the upper chambers and lower chambers meet.

As the heart formed abnormally, the valves that separate the upper and lower chambers also developed abnormally. In a normal heart, two valves separate the upper and lower chambers of the heart: the tricuspid valve separates the right chambers and the mitral valve the left chambers. In a child with a complete atrioventricular canal defect, there is one large valve, and it may not close correctly.

As a result of the abnormal passageway between the two sides of the heart, blood from both sides mix, and too much blood circulates back to the lungs before it travels through the body. This means the heart works harder than it should have to, often becoming enlarged and damaged if the problems aren’t repaired.

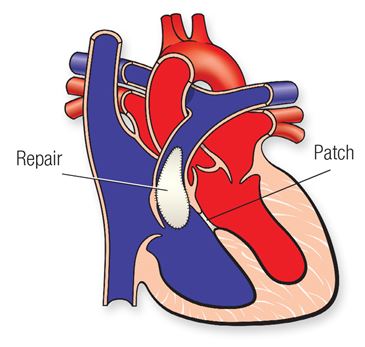

A CAVC prevents oxygen-rich blood from going to the right places in your body. Your doctor can repair it with patches. But some people need more than one surgery to treat it.

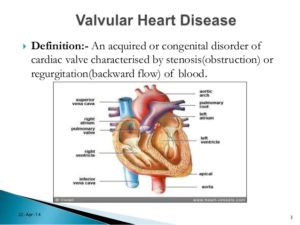

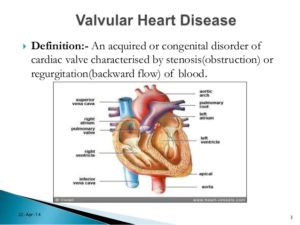

2-Types of Heart Valve Defects

Valves control the flow of blood through your heart’s ventricles and arteries. And some minor heart defects can involve the valves. Your heart has four valves aortic, pulmonic, tricuspid, and mitral valve. All four of them can develop different kinds of heart valve disease, this would include stenosis, regurgitation, and atresia.

a Stenosis.

When your cardiac valves become involved with stenosis where they narrow or stiffen, and won’t open or allow properly from a little amount to completely closed. Ranging the blood to pass easily to not at all depending on the extent of the stenosis to the valve. This makes treatment range from none and just medication if needed at all to surgery later in life or immediately born, again depending on the extent of cardiac valvular stenosis.

Aortic Valve Stenosis:

Aortic valve stenosis is most common in the world and in elderly, becoming more and more common after age 65. Several diseases can also cause it to develop in people when they reach middle age. The bicuspid aortic valve is the most common cause of aortic stenosis in patients less than the age of 70 years in developed countries. Rheumatic valve disease is the most common cause in developing countries. Although some people have aortic stenosis because of a congenital heart defect called a bicuspid aortic valve, this condition more commonly develops during aging as calcium or scarring damages the valve, that is a common cause for this condition in elderly pts since it takes time to develop calcium build up in causing the stenosis. This in turn restricts the amount of blood flowing getting through the aorta to deliver that oxygenated blood to the body. The calcium build up takes time to put an affect on the aorta with symptoms as well; so this is why this is commonly seen in elders.

Aortic stenosis is one of the most common and serious valve disease problems. Know the aorta is the main artery bringing blood from the heart to the body’s tissues/organs. Aortic stenosis is a narrowing of the aortic valve opening, and can sometimes be referred to as a failing heart valve. Aortic stenosis restricts the blood flow from the left ventricle to the aorta and may also affect the pressure in the left atrium due to the blood flow regurgitating backwards from the stenosis to the L Ventricle up to the L atrium.

The condition may range from mild to severe; the longer you have it the more severe the symptoms and intensity it would have on the heart, especially left untreated.

Over time, aortic valve stenosis causes your heart’s left ventricle to pump harder to push blood through the narrowed aortic valve. The extra effort may cause the left ventricle to thicken, enlarge and weaken. If not addressed, this form of heart valve disease may lead to heart failure known as CHF. This heart failure would start on the Left Side of the Heart first=L CHF and if left untreated it would in time effect the Right Side of the Heart=R CHF as well. The symptoms of L CHF versus R CHF would be different at first and in another topic later this year (over extends this topic for today).

Pulmonary Valve Stenosis:

Pulmonary valve stenosis is a heart valve disorder that involves the pulmonary valve. This is the valve separating the right lower chamber or the right ventricle (one of the chambers in the heart) and the pulmonary artery. Pulmonary artery is one of the few arteries with high carbon dioxide and low oxygen level in the blood stream. This blood flow normally is being sent to the lungs for more oxygen where it will send the blood flow to the left side of the heart to go through the aorta and sent throughout the body to give high oxygen to all organs. This is how we survive; with out oxygen we would be going through cellular starvation and die. The pulmonary artery carries oxygen-poor blood to the lungs as its ending function. Stenosis, or narrowing in the pulmonary valve occurs when the valve cannot open wide enough to its normal capacity or in some cases completely stenosis, not able to open or close at all.

Treatment surgery at some time in the person’s lifetime. It would all depend on the severity of the stenosis condition.

Mitral Valve Stenosis:

Mitral valve stenosis — sometimes called mitral stenosis — is a narrowing of the valve between the two left heart chambers. The narrowed valve reduces or blocks blood flow into the heart’s main pumping chamber. The heart’s main pumping chamber is the lower left heart chamber, also called the left ventricle.

There are two types of mitral valve regurgitation:

- Degenerative mitral regurgitation: This occurs when the mitral valve itself is dysfunctional. The flaps may droop or bulge and do not close tightly.

- Functional mitral regurgitation: Functional mitral regurgitation happens when an issue outside of the valve (such as diseases of the left ventricle) causes the leakage. You may have normal valve flaps and still be diagnosed with functional mitral regurgitation.

Mitral valve stenosis can make you tired and short of breath. Other symptoms may include irregular heartbeats, dizziness, chest pain or coughing up blood. Some people don’t notice symptoms.

Mitral valve stenosis can be caused by a complication by a sore throat with strep throat called rheumatic fever. Rheumatic fever is now rare in the United States.

Treatment for mitral valve stenosis may include medication or mitral valve repair or replacement surgery. Some people only need regular health checkups. Treatment depends on the severity of the condition and whether it’s getting worse. Untreated, mitral valve stenosis can lead to serious heart complications.

Tricuspid Valve Stenosis:

Tricuspid stenosis (TS) is narrowing of the tricuspid orifice that obstructs blood flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle. Almost all cases result from rheumatic fever. Symptoms include a fluttering discomfort in the neck, fatigue, cold skin, and right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort. Jugular pulsations are prominent, and a presystolic murmur is often heard at the left sternal edge in the fourth intercostal space and is increased during inspiration. Diagnosis is by echocardiography. TS is usually benign, requiring no specific treatment, but symptomatic patients may benefit from surgery.

b Regurgitation.

A damaged or diseased valve can severely compromise the ability of the heart in inefficiently which in turn does not let oxygen or carbon dioxide to be used or removed from the body in the way its suppose to be and in time effects the heart and can lead to heart failure if left untreated. Instead of the valve having stenosis it is now not closing completely when it should allowing regurgitation to occur.

Your valves don’t close tightly, the valve affected will allow regurgitation due to the valve not working efficiently with opening and closing the way it should during your heart beat (lub dub-the sound you hear of the heart when auscultating through the stethoscope, the RN or doctor uses.) Instead this lets your blood flow or leak backward r/t the valve partially open or to completely opened when the valve should be closely closed at that time and results into regurgitation. Remember the cardiac valves open and close as their function to allow blood flowing with a heart pumping to deliver oxygen to the blood from red blood cells that carry O2 and remove carbon dioxide blood through red blood cells carrying it out of the blood stream back to the lungs to get more O2 for the RBCs to carrying it to organs / tissues that need it to survive. Depending on the extent of valvular regurgitation will decide on treatment which ranges from surgery later in life or immediately when born.

It does the opposite of valve stenosis in that stenosis is a narrowing of the vessel whereas regurgitation is due to a valve remaining open partially or completely when the valve is suppose to be closing to allow blood fill up in the chamber of the heart and common one is mitral valve regurgitation but there are others like tricuspid, pulmonary and ventricular valve regurgitation.

Mitrial Valve Regurgitation:

Mitral valve regurgitation is the most common type of heart valve disease. In this condition, the valve between the left heart chambers doesn’t close fully. Blood leaks backward across the valve. If the leakage is severe, not enough blood moves through the heart or to the rest of the body. Mitral valve regurgitation can make you feel very tired or short of breath.

Other names for mitral valve regurgitation are:

- Mitral regurgitation (MR).

- Mitral insufficiency.

- Mitral incompetence.

Treatment of mitral valve regurgitation may include regular health checkups, medicines or surgery. You may not need treatment if the condition is mild.

Severe mitral valve regurgitation often requires a catheter procedure or heart surgery to repair or replace the mitral valve. Without proper treatment, severe mitral valve regurgitation can cause heart rhythm problems or heart failure.

Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation:

Tricuspid valve disease is a type of heart valve disease (valvular heart disease). The valve between the two right heart chambers (right atrium and right ventricle) doesn’t work properly. As a result, the heart must work harder to send blood to the lungs and the rest of the body.

Tricuspid valve disease often occurs with other heart valve problems.

Symptoms and treatments of tricuspid valve disease vary, depending on the specific valve condition. Treatment may include monitoring, medication, or valve repair or valve replacement.

The most common cause of tricuspid regurgitation is enlargement of the right ventricle. Pressure from heart conditions, such as heart failure, pulmonary hypertension and cardiomyopathy, cause the ventricle to expand. The result is a misshapen tricuspid valve that is leaky and cannot close properly.

Aortic Valve Regurgitation:

Aortic valve regurgitation — also called aortic regurgitation — is a type of heart valve disease. The valve between the lower left heart chamber and the body’s main artery doesn’t close tightly. As a result, some of the blood pumped out of the heart’s main pumping chamber, called the left ventricle, leaks backward.

The leakage may prevent the heart from doing a good enough job of pumping blood to the rest of the body. You may feel tired and short of breath.

Aortic valve regurgitation can develop suddenly or over many years. Once the condition becomes severe, surgery often is needed to repair or replace the valve.

Pulmonary Valve Regurgitation:

Pulmonary valve disease affects the valve between the heart’s lower right chamber and the artery that delivers blood to the lungs. That artery is called the pulmonary artery. The valve is called the pulmonary valve.

A diseased pulmonary valve doesn’t work properly. Pulmonary valve disease changes how blood flows from the heart to the lungs.

The pulmonary valve usually acts like a one-way door from the lower right heart chamber to the lungs. Blood flows from the chamber through the pulmonary valve. It then goes to the pulmonary artery and into the lungs. Blood picks up oxygen in the lungs to take to the body.

Many types of pulmonary valve disease are due to heart conditions present at birth. Treatment depends on the type and severity of pulmonary valve disease.

c Atresia.

Tricuspid Atresia:

This happens when your valve isn’t formed right or has no opening to let your blood pass through. It causes more complicated heart problems. Tricuspid atresia (pronounced try-CUSP-id uh-TREE-zhuh) is a birth defect of the heart where the valve that controls blood flow from the right upper chamber of the heart to the right lower chamber of the heart doesn’t form at all. In babies with this defect, blood can’t flow correctly through the heart and to the rest of the body.

Aortic Atresia:

Aortic valvular atresia is a congenital condition in which the aortic valvular cusps are fused at birth. It frequently forms as a spectrum of malformations of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT). The atresia can be characterized as sub-valvular, valvular, or supra-valvular, depending on the site of the anomaly. Most commonly, the defect presents as aortic stenosis, though in rare cases, it can manifest as complete atresia.

Pulmonary Atresia

Pulmonary atresia is a birth defect of the pulmonary valve, which is the valve that controls blood flow from the right ventricle (lower right chamber of the heart) to the main pulmonary artery (the blood vessel that carries blood from the heart to the lungs). Pulmonary atresia is when this valve didn’t form at all, and no blood can go from the right ventricle of the heart out to the lungs. Because a baby with pulmonary atresia may need surgery or other procedures soon after birth, this birth defect is considered a critical congenital heart defect (critical CHD). Congenital means present at birth.

In a baby without a congenital heart defect, the right side of the heart pumps oxygen-poor blood from the heart to the lungs through the pulmonary artery. The blood that comes back from the lungs is oxygen-rich and can then be pumped to the rest of the body. In babies with pulmonary atresia, the pulmonary valve that usually controls the blood flowing through the pulmonary artery is not formed, so blood is unable to get directly from the right ventricle to the lungs.

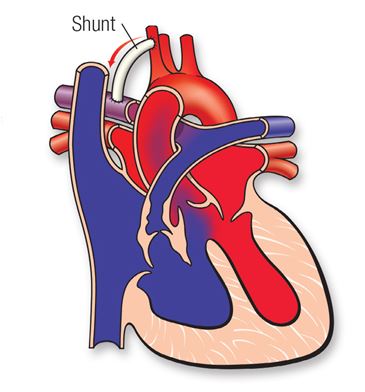

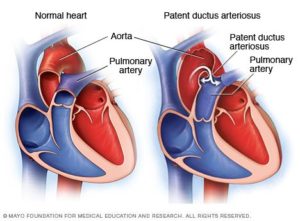

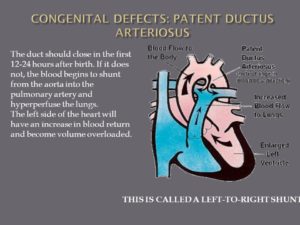

In pulmonary atresia, since blood cannot directly flow from the right ventricle of the heart out to the pulmonary artery, blood must use other routes to bypass the unformed pulmonary valve. The foramen ovale, a natural opening between the right and left upper chambers of the heart during pregnancy that usually closes after the baby is born, often remains open to allow blood flow to the lungs. Additionally, doctors may give medicine to the baby to keep the baby’s patent ductus arteriosus open after the baby’s birth. The patent ductus arteriosus is the blood vessel that allows blood to move around the baby’s lungs before the baby is born and it also usually closes after birth.

d Ebstein’s anomaly.

This is a defect in another heart valve, the tricuspid valve-between the top and bottom of the right side of the heart, which may keep it from closing tightly. Ebstein anomaly is a rare heart problem present at birth. This means it’s a congenital heart defect. The tricuspid valve is incorrectly formed and located lower than usual in the heart. The condition may occur with a hole between the two upper chambers of the heart, called an atrial septal defect.Babies who have Ebstein’s also often have an atrial septal defect (ASD).

In people with Ebstein anomaly, the heart can grow larger. The condition can lead to heart failure.

Treatment of Ebstein anomaly depends on the symptoms. Some people without symptoms only need regular health checkups. Others may need medicines and surgery.

Keep in mind a baby can be born with more than one cardiac defect depending on the pt’s heart formation during pregnancy or at birth or in some cases symptoms arise later in life and that could be the time the patient is diagnosed with the heart condition they have. Symptoms help tell the doctor there is a problem so diagnosing gets involved until the etiology is found. If it is your heart your MD will find the defect no problem.

Part II tomorrow on other defects!