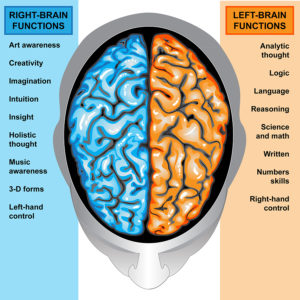

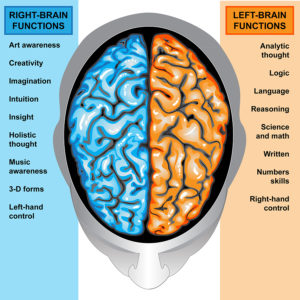

IIlustration body part,human brain left and right functions

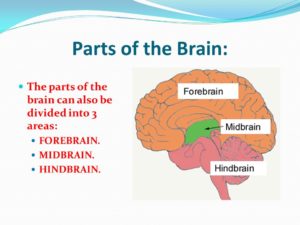

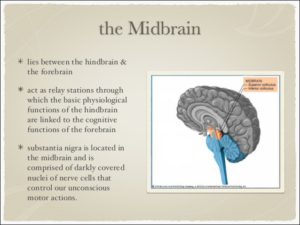

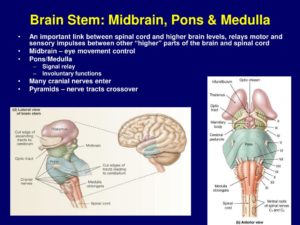

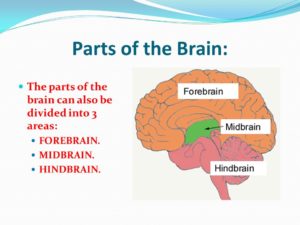

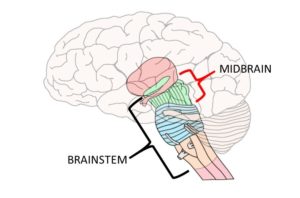

The brain is like a committee of experts. All the parts of the brain work together, but each part has its own special properties. The brain can be divided into three basic units: 1 the forebrain, 2 the midbrain, and 3 the hindbrain.

1-THE CEREBRUM (The Forebrain) AND ITS FUNCTIONS: Knowing what part of the cerebrum, if the brain injury is their, can explain the reasons for the symptoms the individual is having.

1-The forebrain is the largest and most highly developed part of the human brain: it consists primarily of the cerebrum and the structures hidden beneath it, which is the inner brain.

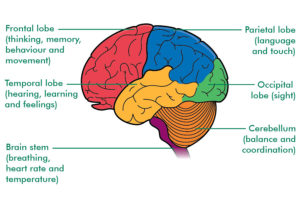

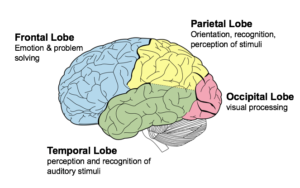

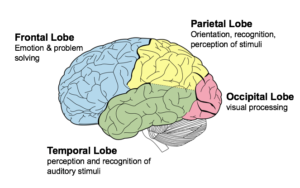

THE REGIONS (The 4 LOBES) THAT MAKE UP THE CEREBRUM:

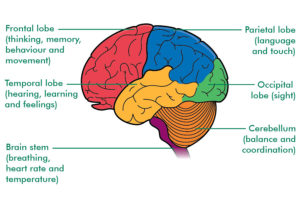

The cerebrum, the large, outer part of the brain, controls reading, thinking, learning, speech, emotions and planned muscle movements like walking. It also controls vision, hearing and other senses. The cerebrum is divided two cerebral hemispheres (halves): left and right. The right half controls the left side of the body. The left half controls the right side of the body.

Each hemisphere has four sections, called lobes: frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital. A lobe simply means a part of an organ (earlobe for example). Each lobe controls specific functions. For example, the frontal lobe controls personality, decision-making and reasoning, while the temporal lobe controls, memory, speech, and sense of smell.

–The frontal lobe is the largest lobe of the brain. The frontal lobe are the last parts of the brain develop as a person ages and the part of the human brain that is most different from other mammals and primates. The last part to mature is the prefrontal lobe. This happens during adolescence. Many things affect brain development including genetics, individual and environmental factors. We learn to become adults in our frontal lobes. You choose between good and bad actions; override and suppress socially unacceptable responses; and determine similarities and differences between objects or situations. The frontal lobe is considered to be the moral center of the brain because it is responsible for advanced decision making processes. It also plays an important role in retaining emotional memories derived from the limbic system, and modifying those emotions to fit socially accepted norms. The frontal lobes are considered our emotional control center and home to our personality. There is no other part of the brain where lesions can cause such a wide variety of symptoms (Kolb & Wishaw, 1990). The frontal lobes are involved in motor function, problem solving, spontaneity, memory, language, initiation, judgment, impulse control, and social and sexual behavior. Frontal lobe damage effects one or more of these areas depending on the severity of the damage. The frontal lobes are extremely vulnerable to injury due to their location at the front of the cranium, proximity to the sphenoid wing and their large size. MRI studies have shown that the frontal area is the most common region of injury following mild to moderate traumatic brain injury.

–The parietal lobes can be divided into two functional regions. One involves sensation and perception and the other is concerned with integrating sensory input, primarily with the visual system. The first function integrates sensory information to form a single perception (cognition). The parietal lobes have an important role in integrating our senses. In most people the left side parietal lobe is thought of as dominant because of the way it structures information to allow us to read & write, make calculations, perceive objects normally and produce language. Damage to the dominant parietal lobe can lead to Gerstmann’s syndrome (e.g. can’t tell left from right, can’t point to named fingers), apraxia and sensory impairment (e.g. touch, pain). Damage to the non-dominant lobe, usually the right side of the brain, will result in different problems. This non-dominant lobe receives information from the occipital lobe and helps provide us with a ‘picture’ of the world around us. Damage may result in an inability to recognize faces, surroundings or objects (visual agnosia). So, someone may recognize your voice, but not your appearance (you sound like my daughter, but you’re not her). Damage to the parietal lobe depends on severity and location of the area. Because this lobe also has a role in helping us locate objects in our personal space, any damage can lead to problems in skilled movements (constructional apraxia) leading to difficulties in drawing or picking objects up.

–The temporal lobes they are in the section of the brain located on the sides of the head behind the temples and cheekbones. It’s responsible for processing auditory information from the ears (hearing). The temporal lobes play an important role in organizing sensory input, auditory perception, language and speech production, as well as short term memory association and formation. The Temporal Lobe mainly revolves around hearing and selective listening. It receives sensory information such as sounds and speech from the ears. It is also the key to being able to comprehend, or understand meaningful speech. In fact, we would not be able to understand someone talking to us, if it wasn’t for the temporal lobe. This lobe is special because it makes sense of the all the different sounds and pitches (different types of sound) being transmitted from the sensory receptors of the ears. Temporal Lobes Kolb & Wishaw (1990) have identified eight principle symptoms of temporal lobe damage: 1) disturbance of auditory sensation and perception, 2) disturbance of selective attention of auditory and visual input, 3) disorders of visual perception, 4) impaired organization and categorization of verbal material, 5) disturbance of language comprehension, 6) impaired long-term memory, 7) altered personality and affective behavior, 8) altered sexual behavior. These can be due to tumors on the right or left side of the temporal lobe, due to seizures in the temporal lobe and if seizures regularly happen to this individual in the temporal region, which causes lack of oxygen to that area of that area of the brain it will effect one or more of the functions of that lobe which we discussed earlier, listed above.

-The last region or lobe that makes up the cerebrum is the occipital lobe. The occipital lobe is important to being able to correctly understand what our eyes are seeing. These lobes have to be very fast to process the rapid information that our eyes are sending. This is similar to how the temporal lobe makes sense of auditory information, the occipital lobe makes sense of visual information so that we are able to understand it. If our occipital lobe was impaired or injured we would not be able to correctly process visual signals, thus visual confusion would result.

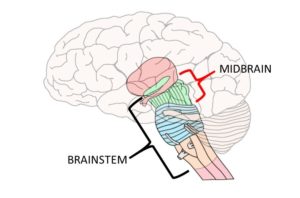

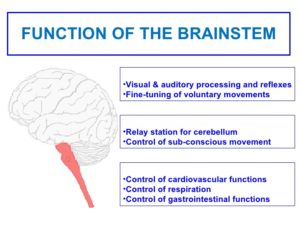

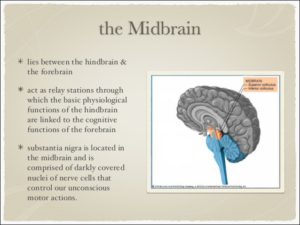

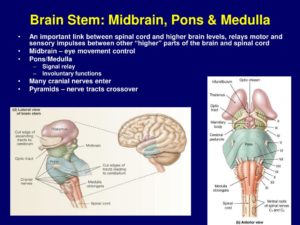

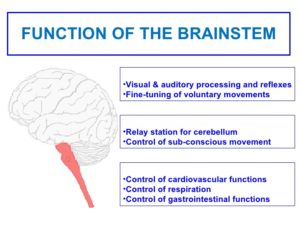

2-Midbrain – The uppermost part of the brainstem is the midbrain, which controls some reflex actions and is part of the circuit involved in the control of eye movements and other voluntary movements.

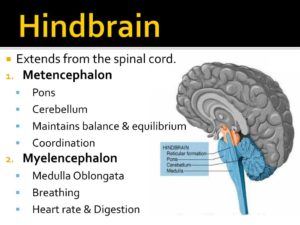

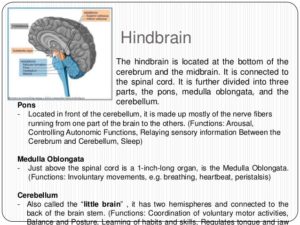

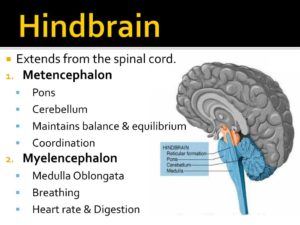

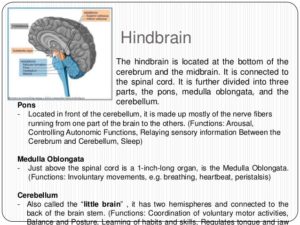

3-The hindbrain includes the upper part of the spinal cord, the brain stem, and a wrinkled ball of tissue called the cerebellum. The hindbrain controls the body’s vital functions such as respiration and heart rate. The cerebellum coordinates movement and is involved in learned rote movements. Rote means “mechanical or habitual repetition of something to be learned.”. Rote learning is flashcards, times tables, any kind of memorization-based learning. Rote movement applies to activities we do in a mechanical, repetitive way. Running, for example. When you play the piano or hit a tennis ball you are activating the cerebellum= balance/coordination.

Knowing how the brain functions to understand this month’s awareness Aphasia (which we will discuss tomorrow).