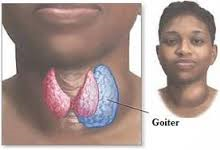

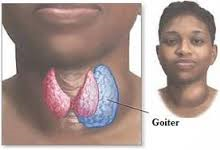

Goiter in the thyroid

A goiter is simply an enlarged thyroid gland. Multiple conditions can lead to goiter, including hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, excessive iodine intake, or thyroid tumors. Goiter is a non-specific finding that warrants medical evaluation.

History: The doctor will take a detailed history, evaluating both past and present medical problems. If the patient is younger than 20 or older than 70 years, there is increased likelihood that a nodule is cancerous. Similarly, the nodule is more likely to be cancerous if there is any history of radiation exposure, difficulty swallowing, or a change in the voice. It was actually customary to apply radiation to the head and neck in the 1950s to treat acne! Significant radiation exposures include the Chernobyl and Fukushima disasters. Although women tend to have more thyroid nodules than men, the nodules found in men are more likely to be cancerous. Despite its value, the history cannot differentiate benign from malignant nodules. Thus, many patients with risk factors uncovered in the history will have benign lesions. Others without risk factors for malignant nodules may still have thyroid cancer.

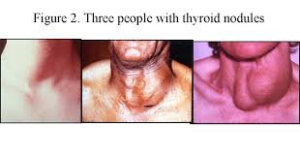

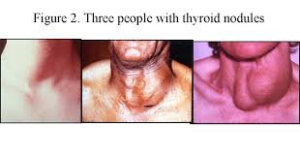

Physical examination: The physician should determine if there is one nodule or many nodules, and what the remainder of the gland feels like. The probability of cancer is higher if the nodule is fixed to the surrounding tissue (unmovable). In addition, the physical exam should search for any abnormal lymph nodes nearby that may suggest the spread of cancer. In addition to evaluating the thyroid, the physician should identify any signs of gland malfunction, such as thyroid hormone overproduction (hyperthyroidism) or underproduction (hypothyroidism).

Blood tests: Initially, blood tests should be done to assess thyroid function. These tests include:

- The free T4 and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels. Elevated levels of the thyroid hormones T4 or T3 in the context of suppressed TSH suggests hyperthyroidism

- Reduced T4 or T3 in the context of high TSH suggests hypothyroidism

- Antibody titers to thyroperoxidase or thyroglobulin may be useful to diagnose autoimmune thyroiditis

- (for example, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis).

- If surgery is likely to be considered for treatment, it is strongly recommended that the physician als determine the level of thyroglobin. Produced only in the thyroid hormone in the blood. Thyroglobulin carries thyroid hormone in the blood. Thyroglobulin levels should fall quickly within 48 hours in the thyroid gland is completely remobed. If thyroglobulin levels start to climb.

- Ultrasonography: A physician may order an ultrasound examination of the thyroid to:

- Detect nodules that are not easily felt

- Determine the number of nodules and their sizes

- Determine if a nodule is solid or cystic

- Assist obtaining tissue for diagnosis from the thyroid with a fine needle aspirate (FNA)Radionuclide scanning: Radionuclide scanning with radioactive chemicals is another imaging technique a physician may use to evaluate a thyroid nodule. The normal thyroid gland accumulates iodine from the blood and uses it to make thyroid hormones. Thus, when radioactive iodine (123-iodine) is administered orally or intravenously to an individual, it accumulates in the thyroid and causes the gland to “light up” when imaged by a nuclear camera (a type of Geiger counter). The rate of accumulation gives an indication of how the thyroid gland and any nodules are functioning. A “hot spot” appears if a part of the gland or a nodule is producing too much hormone. Non-functioning or hypo-functioning nodules appear as “cold spots” on scanning. A cold or non-functioning nodule carries a higher risk of cancer than a normal or hyper-functioning nodule. Cancerous nodules are more likely to be cold, because cancer cells are immature and don’t accumulate the iodine as well as normal thyroid tissue. However, cold spots can also be caused by cysts. This makes the ultrasound a much better tool for determining the need to do an FNA.

- Fine needle aspiration: Fine needle aspiration (FNA) of a nodule is a type of biopsy and the most common, direct way to determine what types of cells are present. The needle used is very thin. The procedure is simple and can be done in an outpatient office, and anesthetic is injected into tissues traversed by the needle. FNA is possible if the nodule is easily felt. If the nodule is more difficult to feel, fine needle aspiration can be performed with ultrasound guidance. The needle is inserted into the thyroid or nodule to withdraw cells. Usually, several samples are taken to maximize the chance of detecting abnormal cells. These cells are examined microscopically by a pathologist to determine if cancer cells are present. The value of FNA depends upon the experience of the physician performing the FNA and the pathologist reading the specimen. Diagnoses that can be made from FNA include:

- Despite its value, the ultrasound cannot determine whether a nodule is benign or cancerous.

- Benign thyroid tissue (non-cancerous) can be consistent with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, a colloid nodule, or a thyroid cyst. This result is reported from approximately 60% of biopsies.

- Cancerous tissue (malignant) can be consistent with diagnosis of papillary, follicular, or medullary cancer. This result is reported from approximately 5% of biopsies. The majority of these are papillary cancers.

- Suspicious biopsy can show a follicular adenoma. Though usually benign, up to 20% of these nodules are found ultimately to be cancerous.

- Non-diagnostic results usually arise because insufficient cells were obtained. Upon repeat biopsy, up to 50% of these cases can be distinguished as benign, cancerous, or suspicious.

One of the most difficult problems for the pathologist is to be confident that a follicular adenoma – usually a benign nodule – is not a follicular cell carcinoma or cancer. In these cases, it is up to the physician and the patient to weigh the option of surgery on a case-by-case basis, with less reliance on the pathologist’s interpretation of the biopsy. It is also important to remember that there is a small risk (3%) that a benign nodule diagnosed by FNA may still be cancerous. Thus, even benign nodules should be followed closely by the patient and physician. Another biopsy may be necessary, especially if the nodule is growing. Most thyroid cancers are not very aggressive; that is, they do not spread rapidly. The exception is poorly differentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma, which spreads rapidly and is difficult to treat.