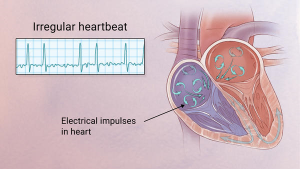

Atrial fibrillation, or AFib, is the most common type of arrhythmia.

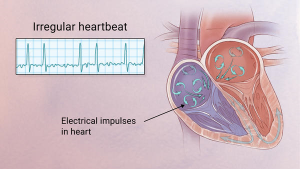

A heart arrhythmia is an abnormal rate or rhythm in your heartbeat. This can mean your heartbeat is too slow, too fast, or has an irregular rhythm.

Most arrhythmias are harmless, and may not cause symptoms. Some types, however, can have serious consequences and require treatment. Dangerous arrhythmias may cause heart failure, stroke, or low blood flow that results in organ damage. Most people with arrhythmias, even serious ones with treatment, live normal and healthy lives.

Working of the heart:

To easily identify atrial fibrillation with RVR=Rapid Ventricular Rate, it is vital to understand the working of the heart. The atrium or atria (plural) is the upper chamber of the heart, bigger in size compared to the lower chambers known as the ventricles. The atria function by gathering blood as it flows into the heart and shrinking to forward the blood into the ventricles. At the very moment, the smaller ventricle must shrink to forward the blood to all parts of the body. This rhythm of blood flow creates a heart signature voice referred to as the Sinus rhythm. It is important that the sinus rhythm is synchronized so that the atrium does not send blood into the ventricle out of cue. To achieve this, an electric signal is generated to ensure the atrium contracts. When this signal short circuits (bypasses) the atrium, atrial fibrillation with RVR occurs, and the atrium is seen to vibrate just like jelly on a flat surface.

Atrial fib with RVR refers to atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate. Usually the heart is like clockwork, the top (collecting) chambers beat then the bottom (main pumping) chambers sense this and also beat, and so on, in a nice regular fashion just like a clock ticking second after second. Usually the heart beats at about 60-80 beats per minute.

In atrial fibrillation the top chamber basically goes crazy often firing off over 400 beats per minute! Atrial fibrillation with RVR (Rapid Ventricular Response) is a heart condition caused by irregular electrical activity that results in irregular contractions of the 2 top heart chambers fibrillating. This means the heart (atriums), shakes with a rapid tremulous movement or makes fine irregular twitching movements, generally referred to as fibrillating causing little control in the heart output of blood by the heart but the lower chambers called the ventricles take over.

These bottom chambers don’t allow all those impulses through but it does let every second or third one through. This can give a heart rate of 100-180 beats per minute at rest, still too many beats, known as Afib with RVR, leading to symptoms and problems with heart function. Afib does not necessarily lead to Afib with RVR however, Afib can be rate controlled, sometimes naturally, sometimes using medications and sometimes requiring procedures as discussed below.

In most people with AFib although symptoms can sometimes be unpleasant it is generally not harmful as long as the afib is controlled, meaning the heart in the afib rhythm with the pulse under 100. The main concern is stroke, but that can be treated with the use of blood thinning medications in people at risk. In Afib with RVR, basically the heart is beating too fast. Of course palpitations are the most common symptom. Other symptoms of AFib with RVR may include dizziness, lack of energy, exercise intolerance and shortness of breath. If Afib with RVR goes on for too long then this may result in heart failure and of course worsening of existing heart failure. Control of the heart rate in patients with Afib with RVR often causes these symptoms to improve, again meaning the HR is under 100 with the heart rhythm in afib.

A major indication of atrial fibrillation with RVR is a very rapid heartbeat rate, although some patients are known to have the condition without showing symptoms. Atrial fibrillation with RVR may occur when cardiac muscle cells overcome their intrinsic pacemaker’s signals and fire rapidly differently from their normal pattern spreading the abnormal activity to the ventricles. The rapid heart rate can strain the heart, developing a situation referred to as Tachycardia (meaning a pulse greater than 100). Atrial fibrillation with RVR can be detected from the various symptoms though it is important to remember that some patients have experienced the condition without symptoms.

Symptoms:Some of the symptoms of this disease include heart palpitations (described as unnoticed skipped beats or skipped beats noticed from experienced dizziness or difficulty in breathing), shortness of breath when lying flat (orthopnea), shortness of breath (dyspnea after exertion) sudden onset of short breath during the night (also called paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea) and gradual swelling of lower extremities. As a result of inadequate blood flow, some patients complain of light headedness and may feel like they are about to faint, a condition referred to as presyncope and may actually lose consciousness (syncope). Some patients experience respiratory distress that results in them appearing blue. A close examination of jugular veins usually reveals elevated pressure in some patients (jugular venous distention). When some patients are subjected to lung examinations, crackles and rales may be observed pointing to possible lung edema.

Importance of proper diagnosis:

A good diagnosis of the symptoms shown by patients is important to ascertain that the patient is suffering from atrial fibrillation with RVR. This is because some forms or irregular and rapid heart rates, tachyarrhythmia, are dangerous and must be ruled out as they are life threatening – such as ventricular tachycardia. Some patients are usually placed on continuous cardio respiratory monitoring, but an electrocardiogram ECG is vital for correct diagnosis.

How is it diagnosed?

Simple, a typical 12 lead electrocardiogram (ECG). This test shows cardiac rhythms which atrial fibrillation is. Rhythms are made up of types of waves that the ECG shows which are P waves, QRS waves, T waves and U waves.

The QRS complexes should be narrow, to signify that they are being initiated by normal conduction of atrial electrical activity through the Intra-ventricular conduction system, or heart conduction system. Wide QRS complexes could point to ventricular tachycardia, although wide complexes may also be an indication of disease processes in the Intra-ventricular conduction system. The R-R internal will also likely be irregular. Meaning measuring from each R section of the QRS rhythm. It is also important to find out if there are triggering causes for the tachycardia which include dehydration, Hypovolemia – a decrease in blood volume, and more specifically decrease in blood plasma volume. You can go ahead to eliminate Acute coronary syndrome – which refers to any diseases that are directly attributed to the obstruction of coronary arteries.

WHAT IS THE TREATMENT:

The cornerstones of atrial fibrillation (AF) management are rate control and anticoagulation and rhythm control for those symptomatically limited by AF. The clinical decision to use a rhythm-control or rate-control strategy requires an integrated consideration of several factors, including degree of symptoms, likelihood of successful cardioversion, presence of comorbidities, and candidacy for AF ablation (eg, catheter-based pulmonary vein electric isolation or surgical ablation.)

A Shock

This is known as cardioversion and is used typically either when an immediate result is required or used when the Afib is of relatively recent onset or only intermittent, and so has more chance of staying in normal rhythm. In cardioversion a small shock is given using defibrillation pads in sync mode. It is done under light anesthesia therefore it doesn’t hurt; pt is sedated if allowable. The Afib may or may not return however. Highier odds the afibrillation could turn back to normal sinus rhythm if this afibrillation is newly diagnosed not chronic.

Rate Control Drugs

The biggest problem in Afib with RVR is too fast a heart rate. In a rhythm control strategy we use drugs such as beta-blockers to slow the heart rate down. These drugs typically will leave the patient in AF. For many people with AF it turns out that a rate control strategy is preferred as it is considered less risky than the rhythm control drugs used to get rid of the AF while being just as effective. In Afib with RVR rate control drugs can often slow the heart rate down fairly quickly and improve symptoms.

In the ER with newly diagnosed with pt stable the MD will order medication to decrease the rate

Rhythm Control Drugs

These medications are generally more powerful than the rate control drugs and attempt to convert the Afib back in to a normal rhythm. They are often given after a shock treatment to try and help the heart stay in normal rhythm. These drugs are also commonly used in hospitalized Afib with RVR patients. The problem with these drugs is that they may have side effects and associated risks. Many patients simply cannot tolerate Afib even if the rate is controlled and therefore require rhythm control drugs. They may be safe and effective however if used in selected patients. In cases of Afib with RVR these medications may need to be used if patients cannot tolerate other rate control medications.

Ablation Procedures

Ablation is a minimally invasive procedures typically done through the groin. They are typically used in patients that have tried, or cannot tolerate medicines for control of AFib. Ablation is typically not used as an emergency treatment of Afib with RVR, rather it is used for stable patients in AF, or those with intermittent AFib that wish to remain in normal rhythm. In patients that have had persistent Afib for a long time these procedures are not likely to be successful in the long term.

Pacemaker

This is typically the last throw of the dice for AF control. In some patients, drugs can either not control the rate in AFib with RVR, or the drugs can simply not be tolerated. In these patients who have no other choice, and in whom it is determined the Afib is causing harmful effects, a procedure called AV node ablation and pacemaker is done. In a relatively minor procedure, a small burn is made to the connection that connects the top and bottom chambers of the heart. A pacemaker is then inserted. This prevents Afib with RVR as although the top chambers continue to fire at a fast rate, the pacemaker now controls the bottom chamber, in a nice regular way. The downside of course is that now although the patient cannot have Afib with RVR, they have a pacemaker rather than the SA Node, our natural pacemaker in the heart in the R upper atrium.

Acute afib RVR patients are more likely to be converted to Normal Sinus Rhythm (the best rhythm you could be in) as opposed to patients with chronic afib. There are complete resolutions for both kind of afib but atrial fibrillation in RVR the heart can handle for only so long and remembering the engine of our body is the heart so take good care of it for if you don’t it could allow you to die.