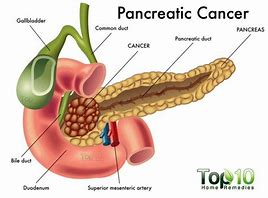

Pancreatic Cancer, its incidence cuts across all racial and socio-economic barriers and is nearly always fatal. 90% die within the 1st yr of diagnosis.

STAGING OF PANCREATIC CANCER

Stage is a term used in cancer treatment to describe the extent of the cancer’s spread. The stages of pancreatic cancer are from 0 to IV.

The best treatment for pancreatic cancer depends on how far it has spread, or its stage. The stages of pancreatic cancer are easy to understand. What is difficult is attempting to stage pancreatic cancer without resorting to major surgery. In practice, doctors choose pancreatic cancer treatments based upon imaging studies, surgical findings, and an individual’s general state of well being.

Stages of Pancreatic Cancer

Stage is a term used in cancer treatment to describe the extent of the cancer’s spread. The stages of pancreatic cancer are used to guide treatment and to classify patients for clinical trials. The stages of pancreatic cancer are:

- Stage 0: No spread. Pancreatic cancer is limited to top layers of cells in the ducts of the pancreas. The pancreatic cancer is not visible on imaging tests or even to the naked eye.

- Stage I: Local growth. Pancreatic cancer is limited to the pancreas, but has grown to less than 2 centimeters across (stage IA) or greater than 2 but no more than 4 centimeters (stage IB).

- Stage II: Local spread. Pancreatic cancer is over 4 centimeters and is either limited to the pancreas or there is local spread where the cancer has grown outside of the pancreas, or has spread to nearby lymph nodes. It has not spread to distant sites.

- Stage III: Wider spread. The tumor may have expanded into nearby major blood vessels or nerves, but has not metastasized to distant sites.

- Stage IV: Confirmed spread. Pancreatic cancer has spread to distant organs.

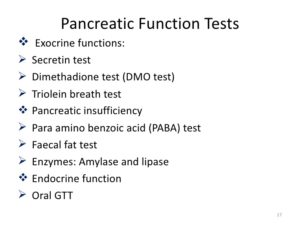

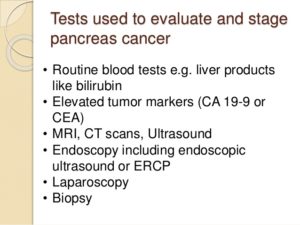

Determining pancreatic cancer’s stage is often tricky. Imaging tests like CT scans and ultrasound provide some information, but knowing exactly how far pancreatic cancer has spread usually requires surgery.

Since surgery has risks, doctors first determine whether pancreatic cancer appears to be removable by surgery (resectable). Pancreatic cancer is then described as follows:

- Resectable: On imaging tests, pancreatic cancer hasn’t spread (or at least not far), and a surgeon feels it might all be removable. About 10% of pancreatic cancers are considered resectable when first diagnosed.

- Locally advanced (unresectable): Pancreatic cancer has grown into major blood vessels on imaging tests, so the tumor can’t safely be removed by surgery.

- Metastatic: Pancreatic cancer has clearly spread to other organs, so surgery cannot remove the cancer.

If pancreatic cancer is resectable, surgery followed by chemotherapy or radiation or both may extend survival.

Treating Resectable Pancreatic Cancer

People whose pancreatic cancer is considered resectable may undergo one of three surgeries:

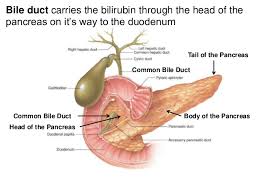

Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy): A surgeon removes the head of the pancreas and sometimes the body of the pancreas, parts of the stomach and small intestine, some lymph nodes, the gallbladder, and the common bile duct. The remaining organs are reconnected in a new way to allow digestion. The Whipple procedure is a difficult and complicated surgery. Surgeons and hospitals that do the most operations have the best results.

About half the time, once a surgeon sees inside the abdomen, pancreatic cancer that was thought to be resectable turns out to have spread, and thus be unresectable. The Whipple procedure is not completed in these cases.

Distal pancreatectomy: The tail and/or portion of the body of the pancreas are removed, but not the head. This surgery is uncommon for pancreatic cancer, because most tumors arising outside the head of the pancreas within the body or tail are unresectable.

Total pancreatectomy: The entire pancreas and the spleen is surgically removed. Although once considered useful, this operation is uncommon today.

Chemotherapy or radiation therapy or both can also be used in conjunction with surgery for resectable and unresectable pancreatic cancer in order to:

- Shrink pancreatic cancer before surgery, improving the chances of resection (neoadjuvant therapy)

- Prevent or delay pancreatic cancer from returning after surgery (adjuvant therapy)

Chemotherapy includes cancer drugs that travel through the whole body. Chemotherapy (“chemo”) kills pancreatic cancer cells in the main tumor as well as those that have spread widely. These chemotherapy drugs can be used for pancreatic cancer:

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or capecitabine

- Gemcitabine

Both 5-FU and gemcitabine are given into the veins during regular visits to an oncologist (cancer doctor). An oral drug, capecitabine, may be substituted for 5-FU, especially with radiation.

In radiation therapy, a machine beams high-energy X-rays to the pancreas to kill pancreatic cancer cells. Radiation therapy is done during a series of daily treatments, usually over a period of weeks.

Both radiation therapy and chemotherapy damage some normal cells, along with cancer cells. Side effects can include nausea, vomiting, appetite loss, weight loss, and fatigue as well as toxicity to the blood cells. Symptoms usually cease within a few weeks after radiation therapy is complete.

The best treatment for pancreatic cancer depends on how far it has spread, or its stage. The stages of pancreatic cancer are easy to understand. What is difficult is attempting to stage pancreatic cancer without resorting to major surgery. In practice, doctors choose pancreatic cancer treatments based upon imaging studies, surgical findings, and an individual’s general state of well being.

Treating Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer

In metastatic pancreatic cancer, surgery is used only for symptom control, such as for pain, jaundice, or gastric outlet obstruction. Radiation may be used for symptom relief, as well.

Chemotherapy can also help improve pancreatic cancer symptoms and survival. Gemcitabine has been the most wildly used chemotherapy drug for treating metastatic pancreas cancer. Other drug combinations include gemcitabine with erlotinib, gemcitabine with capecitabine, gemcitabine with cisplatin, and gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel. If you’re in fairly good health you may receive FOLFIRINOX (5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin/irinotecan). Other combinations include gemcitabine alone or with another agent like (nab)-paclitaxel or capecitabine. Next line drug combinations to treat pancreatic cancer include oxaliplatin/fluoropyrimidine, or irinotecan liposome (Onivyde) in combination with fluorouracil plus leucovorin.

Palliative Treatment for Pancreatic Cancer

As pancreatic cancer progresses, the No. 1 priority of treatment will shift from extending life to alleviating symptoms, especially pain. Numerous treatments can help protect against the discomfort from advanced pancreatic cancer:

- Procedures like bile duct stents can relieve jaundice, thus reducing itching and loss of appetite associated with bile obstruction.

- Opioid analgesics and a nerve block called a celiac plexus block can help relieve pain.

- Antidepressants and counseling can help treat depression common in advanced pancreatic cancer.

Clinical Trials for Pancreatic Cancer

New pancreatic cancer treatments are constantly being tested in clinical trials. You can find out about clinical trials for the latest treatments for pancreatic cancer on the websites of the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute