Sleep isn’t just a time to rest and give your body and brain a break. It’s a critical biological function that restores and replenishes important body systems. Now, yet another study on shift workers shows that their unusual hours may be cutting their lives short—and that’s especially true for those who have rotating night shifts, rather than permanent graveyard duty.

You wake up, feel hungry, and fall asleep each day around repeating 24-hour “circadian” cycles controlled by your body’s internal clocks. These clocks are synchronized by a central pacemaker in the brain. Cycles of light and dark are important for the function of the brain’s master clock. Other cycles, such as the behavioral activities of eating and fasting or sleeping and waking, are important for peripheral clocks in the liver, gut, and other tissues.

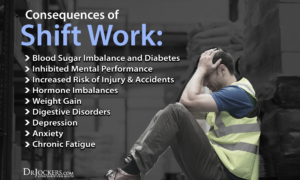

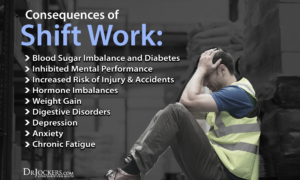

When you stay awake all night or otherwise go against natural light cycles, your health may suffer. Long-term disruption of circadian rhythms has been linked to obesity, diabetes, and other health problems related to the body’s metabolism.

In a study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, scientists led by Dr. Eva Schernhammer, an epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, studied 74,862 nurses enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study since 1976. The nurses were an ideal group for studying the effects of rotating night shifts on the body, since RNs tend to have changing night shift obligations over an average month rather than set schedules.

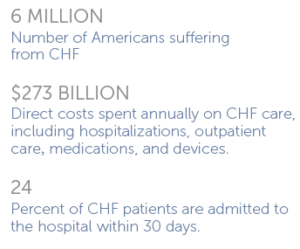

After 22 years, researchers found that the women who worked on rotating night shifts for more than five years were up to 11% more likely to have died early compared to those who never worked these shifts. In fact, those working for more than 15 years on rotating night shifts had a 38% higher risk of dying from heart disease than nurses who only worked during the day. Surprisingly, rotating night shifts were also linked to a 25% higher risk of dying from lung cancer and 33% greater risk of colon cancer death. The increased risk of lung cancer could be attributed to a higher rate of smoking among night shift workers, says Schernhammer.

The population of nurses with the longest rotating night shifts also shared risk factors that endangered their health: they were heavier on average than their day-working counterparts, more likely to smoke and have high blood pressure, and more likely to have diabetes and elevated cholesterol. But the connection between more rotating night shift hours and higher death rates remained strong after the scientists adjusted for them.

You wake up, feel hungry, and fall asleep each day around repeating 24-hour “circadian” cycles controlled by your body’s internal clocks. These clocks are synchronized by a central pacemaker in the brain. Cycles of light and dark are important for the function of the brain’s master clock. Other cycles, such as the behavioral activities of eating and fasting or sleeping and waking, are important for peripheral clocks in the liver, gut, and other tissues.

When you stay awake all night or otherwise go against natural light cycles, your health may suffer. Long-term disruption of circadian rhythms has been linked to obesity, diabetes, and other health problems related to the body’s metabolism.

Previous studies have shown that some metabolites—the products of metabolism—in blood can have daily rhythms. An international research team led by Drs. Hans P. A. Van Dongen and Shobhan Gaddameedhi at Washington State University investigated whether disruptions in these rhythms are influenced by the central pacemaker in the brain or reflect behavioral activities, such as working the night shift. The study was funded in part by NIH’s National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). Results were published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on July 10, 2018.

Ten men and four women, aged 22 to 34 years, stayed at a research lab for one week. Half had a night-shift sleep pattern for three days and half had a day-shift pattern. The night-shift pattern causes the central pacemaker and behavioral rhythms to be at odds. After three days, the volunteers were kept awake for one day in a constant routine with a constant level of temperature and light. They received identical snacks every hour and provided blood samples every three hours.

The research team found only small differences in the day-shift and night-shift patterns for melatonin and cortisol, which mark the activity of the brain’s master clock. This finding suggests that the master clock is resistant to influence from the night-shift pattern.

The team analyzed the levels of 132 metabolites during the 24-hour constant routine. About half (65) of the metabolites had a significant daily rhythm. Of these, 27 had a significant 24-hour rhythm for both sleep patterns. Only three of these metabolites (taurine, serotonin, and sarcosine) kept the same peak time, similar to the master clock markers melatonin and cortisol. The other 24 showed a 12-hour shift in rhythm for the night-shift pattern.

The researchers noted that the particular metabolites and pathways affected by the night-shift sleep pattern relate to the liver, pancreas, and digestive tract. These findings suggest that night-shift sleep patterns can disrupt certain metabolite rhythms and the peripheral clocks of the digestive system without affecting the brain’s master clock.

“No one knew that biological clocks in people’s digestive organs are so profoundly and quickly changed by shift work schedules, even though the brain’s master clock barely adapts to such schedules,” Van Dongen says. “As a result, some biological signals in shift workers’ bodies are saying it’s day while other signals are saying it’s night, which causes disruption of metabolism.”

Further research is needed to better understand the role of these metabolic pathways in obesity, diabetes, and other medical conditions for which shift workers are at increased risk.

Nearly 15 million Americans work a permanent night shift or regularly rotate in and out of night shifts, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That means a significant sector of the nation’s work force is exposed to the hazards of working nights, which include restlessness, sleepiness on the job, fatigue, decreased attention and disruption of the body’s metabolic process.

Those effects extend beyond the workers themselves, as many of us share the road with night-driving truckers, count on the precision of emergency-room workers and rely on the protection of police and national security personnel at all hours.

Now, psychologists are gaining a better understanding of how exactly night and shift work affect cognitive performance and which interventions and policies could keep shift workers and the public safer.

“The basic take-home is that fatigue decreases safety,” says Bryan Vila, PhD, a sleep expert and criminal justice researcher at Washington State University–Spokane. Learning healthy sleeping practices is “just as important as occupational training,” he says.

Poor scheduling, combined with unhealthy attitudes about the need for sleep, can cause major problems for night workers. That’s because working at night runs counter to the body’s natural circadian rhythm, says Charmane Eastman, PhD, a physiological psychologist at Rush University in Chicago. The circadian clock is essentially a timer that lets various glands know when to release hormones and also controls mood, alertness, body temperature and other aspects of the body’s daily cycle.

Possible solutions

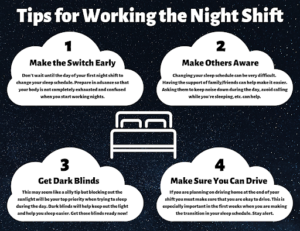

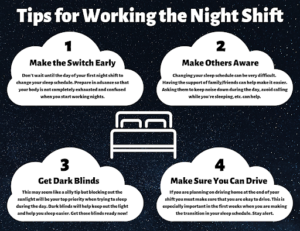

Of course, many workers can’t give up the night shift entirely. So the question is, how can night shift workers adapt to their schedules?

Charmane Eastman, PhD. Founding Director, Biological Rhythms Research Lab. Her education is PhD, University of Chicago / BS, State University of New York at Albany. Her Research Areas are: Shift work, jet lag, human circadian rhythms (especially effects of bright light and melatonin), social jet lag, circadian misalignment

There are two ways, says Rush University’s Eastman. One is through symptomatic relief by using such stimulants as coffee and caffeine pills to stay awake during the night, then taking sedatives to sleep in the morning. The other way is to shift the body’s circadian clock so that it better tolerates working at night and sleeping during the day.

Eastman and her team are exploring the latter approach. “The circadian clock is very stubborn and hard to push around,” she says.

Previous research has established that you can delay the circadian clock by about one or two hours per day. To determine that, researchers measure the body’s circadian rhythm by monitoring “dim-light melatonin onset,” or the time at which the pineal gland begins to secrete melatonin, which is triggered by the circadian clock. Normally, it kicks in a couple hours before people are ready to sleep. “It’s an output that’s a way of seeing what the circadian clock is doing,” Eastman says. “It’s a very good marker of the phase of the time of the clock.”

By exposing experimental subjects to intermittent bright light during their night shifts and having them wear sunglasses on their way home and sleeping in very dark bedrooms, Eastman and her team have found that within about a week, they can shift someone’s circadian rhythm to align perfectly with working a night shift and sleeping during the day.

Through WebMD.com it points out March 2010 the following: In terms of lifestyle, working odd hours leads to some obvious problems. People who do shift work tend to have sleep disturbances and sleep loss. They might feel isolated, since their jobs cut them off from their friends and families. They might find it harder to exercise regularly, and may be prone to eat junk food out of a handy vending machine, says Scheer.

Including in this note, I myself, being a RN 35 years basically, who has worked all shifts (mostly 12 hr shifts than driving home and for the past 4.5 years a 2 hr drive to and back to the hospital) disagree with this statement in that preventing junk food and of course exercise in your week you need discipline in obtaining right foods, exercise and habits. It is a challenge with no question but can be obtained if the right mind is set to it.

As WebMD points out, “The long-term effects of shift work are harder to measure. But researchers have found compelling connections between shift workers and an increased risk of serious health conditions and diseases.”. It really depends on what where you prior to going into night shift, is it 12 hr shifts or 8 hr shifts or part time or perdiem. It messes up the circadium cycle but you can bounce back depending on often you work night shift. ”

Remember, I point out night shift is not 3 to 11 pm but 11pm and on till am in long hours. Since many don’t fall asleep till after 10pm and on. Another major ingredient I would like to point out is, what is your medically history? Is this a worker with no medical history/in shape/ and great health habits? What is your age? Is this worker someone who is with diabetes?, cardiac disease?, overweight? etc… We need to look at the whole picture always!

Scheer backs my statement up with the following: “”There is strong evidence that shift work is related to a number of serious health conditions, like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity,” says Frank Scheer PhD,. “These differences we’re seeing can’t just be explained by lifestyle or socioeconomic status.”

Scheer in Web MD states “It’s important to keep the risks in perspective. Even if performing shift work is a risk factor for some diseases, it’s only one of many — just like not getting enough sleep or eating too many sweets. If you’re in good health to begin with, the overall risks to any given person performing shift work remain low. Scheer states he cautions that the implications of the study, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2009, are limited. A small laboratory experiment can’t fully reflect what’s happening to actual shift workers. It’s also possible that some of these health effects might improve as people get used to shift work. On the other hand, it’s also possible that these effects would just worsen over time. For now, we don’t know.

Keep in mind the things listed in books, internet and etc… are all based on experiments with including theory/principle based on knowing how the anatomy and physiology of the body works under stress or not stressed and how the body is taken care of by that individual is a major role in the turn out of night shift working.