How is dumping syndrome diagnosed?

A health care provider will diagnose dumping syndrome primarily on the basis of symptoms. A scoring system helps differentiate dumping syndrome from other GI problems. The scoring system assigns points to each symptom and the total points result in a score. A person with a score above 7 likely has dumping syndrome.

The following tests may confirm dumping syndrome and exclude other conditions with similar symptoms:

- A modified oral glucose tolerance test checks how well insulin works with tissues to absorb glucose. A health care provider performs the test during an office visit or in a commercial facility and sends the blood samples to a lab for analysis. The person should fast—eat or drink nothing except water—for at least 8 hours before the test. The health care provider will measure blood glucose concentration, hematocrit—the amount of red blood cells in the blood—pulse rate, and blood pressure before the test begins. After the initial measurements, the person drinks a glucose solution. The health care provider repeats the initial measurements immediately and at 30-minute intervals for up to 180 minutes. A health care provider often confirms dumping syndrome in people with

- low blood sugar between 120 and 180 minutes after drinking the solution

- an increase in hematocrit of more than 3 percent at 30 minutes

- a rise in pulse rate of more than 10 beats per minute after 30 minutes

- A gastric emptying scintigraphy test involves eating a bland meal—such as eggs or an egg substitute—that contains a small amount of radioactive material. A specially trained technician performs this test in a radiology center or hospital, and a radiologist—a doctor who specializes in medical imaging—interprets the results. Anesthesia is not needed. An external camera scans the abdomen to locate the radioactive material. The radiologist measures the rate of gastric emptying at 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours after the meal. The test can help confirm a diagnosis of dumping syndrome.

The health care provider may also examine the structure of the esophagus, stomach, and upper small intestine with the following tests:

- An upper GI endoscopy involves using an endoscope—a small, flexible tube with a light—to see the upper GI tract. A gastroenterologist—a doctor who specializes in digestive diseases—performs the test at a hospital or an outpatient center. The gastroenterologist carefully feeds the endoscope down the esophagus and into the stomach and duodenum. A small camera mounted on the endoscope transmits a video image to a monitor, allowing close examination of the intestinal lining. A person may receive general anesthesia or a liquid anesthetic that is gargled or sprayed on the back of the throat. If the person receives general anesthesia, a health care provider will place an intravenous (IV) needle in a vein in the arm. The test may show ulcers, swelling of the stomach lining, or cancer.

- An upper GI series examines the small intestine. An x-ray technician performs the test at a hospital or an outpatient center and a radiologist interprets the images. Anesthesia is not needed. No eating or drinking is allowed before the procedure, as directed by the health care staff. During the procedure, the person will stand or sit in front of an x-ray machine and drink barium, a chalky liquid. Barium coats the small intestine, making signs of a blockage or other complications of gastric surgery show up more clearly on x rays.

A person may experience bloating and nausea for a short time after the test. For several days afterward, barium liquid in the GI tract causes white or light-colored stools. A health care provider will give the person specific instructions about eating and drinking after the test.

How is dumping syndrome treated?

Treatment for dumping syndrome includes changes in eating, diet, and nutrition; medication; and, in some cases, surgery. Many people with dumping syndrome have mild symptoms that improve over time with simple dietary changes.

Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

The first step to minimizing symptoms of dumping syndrome involves changes in eating, diet, and nutrition, and may include

- eating five or six small meals a day instead of three larger meals

- delaying liquid intake until at least 30 minutes after a meal

- increasing intake of protein, fiber, and complex carbohydrates—found in starchy foods such as oatmeal and rice

- avoiding simple sugars such as table sugar, which can be found in candy, syrup, sodas, and juice beverages

- increasing the thickness of food by adding pectin or guar gum—plant extracts used as thickening agents

Some people find that lying down for 30 minutes after meals also helps reduce symptoms.

Medication

A health care provider may prescribe octreotide acetate (Sandostatin) to treat dumping syndrome symptoms. The medication works by slowing gastric emptying and inhibiting the release of insulin and other GI hormones. Octreotide comes in short- and long-acting formulas. The short-acting formula is injected subcutaneously—under the skin—or intravenously—into a vein—two to four times a day. A health care provider may perform the injections or may train the patient or patient’s friend or relative to perform the injections. A health care provider injects the long-acting formula into the buttocks muscles once every 4 weeks. Complications of octreotide treatment include increased or decreased blood glucose levels, pain at the injection site, gallstones, and fatty, foul-smelling stools.

Surgery

A person may need surgery if dumping syndrome is caused by previous gastric surgery or if the condition is not responsive to other treatments. For most people, the type of surgery depends on the type of gastric surgery performed previously. However, surgery to correct dumping syndrome often has unsuccessful results.

Points to Remember

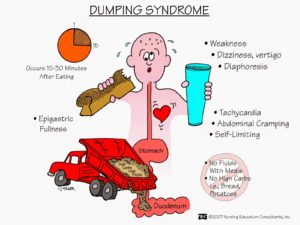

- Dumping syndrome occurs when food, especially sugar, moves too fast from the stomach to the duodenum—the first part of the small intestine—in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

- Dumping syndrome has two forms, based on when symptoms occur:

- early dumping syndrome—occurs 10 to 30 minutes after a meal

- late dumping syndrome—occurs 2 to 3 hours after a meal

- People who have had surgery to remove or bypass a significant part of the stomach are more likely to develop dumping syndrome. Other conditions that impair how the stomach stores and empties itself of food, such as nerve damage caused by esophageal surgery, can also cause dumping syndrome.

- Early dumping syndrome symptoms include

- nausea

- vomiting

- abdominal pain and cramping

- diarrhea

- feeling uncomfortably full or bloated after a meal

- sweating

- weakness

- dizziness

- flushing, or blushing of the face or skin

- rapid or irregular heartbeat

- The symptoms of late dumping syndrome include

- hypoglycemia

- sweating

- weakness

- rapid or irregular heartbeat

- flushing

- dizziness

- Treatment for dumping syndrome includes changes in eating, diet, and nutrition; medication; and, in some cases, surgery. Many people with dumping syndrome have mild symptoms that improve over time with simple dietary changes.