Parkinson’s disease is the second most common progressive, neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer disease. Parkinson’s disease is named after James Parkinson, a 19th century general practitioner in London.

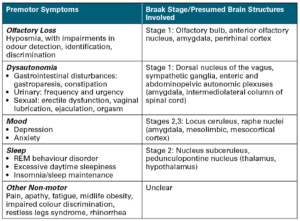

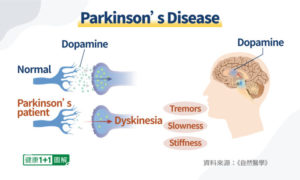

Parkinson’s disease is characterised by pathologic intra-neuronal α–synuclein-positive Lewy bodies and neuronal cell loss. Classically this process has been described as involving the dopaminergic cells of the substantia nigra pars compacta, later becoming more widespread in the CNS as the disease progresses. However, recently there has been a growing awareness that the disease process may involve more caudal portion of the CNS and the peripheral nervous system prior to the clinical onset of the disease.1 Parkinson’s disease affects movement, muscle control, balance, and numerous other functions.

TREATMENTS:

MEDS: The combination of levodopa and carbidopa (Brand names Sinemet, Parcopa, Duopa® (as a combination product containing Carbidopa, Levodopa=Rytary® (as a combination product containing Carbidopa, Levodopa).

Levodopa and carbidopa are used to treat the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s-like symptoms that may develop after encephalitis (swelling of the brain) or injury to the nervous system caused by carbon monoxide poisoning or manganese poisoning. Parkinson’s symptoms, including tremors (shaking), stiffness, and slowness of movement, are caused by a lack of dopamine, a natural substance usually found in the brain. Levodopa is in a class of medications called central nervous system agents. It works by being converted to dopamine in the brain. Carbidopa is in a class of medications called decarboxylase inhibitors. It works by preventing levodopa from being broken down before it reaches the brain. This allows for a lower dose of levodopa, which causes less nausea and vomiting.

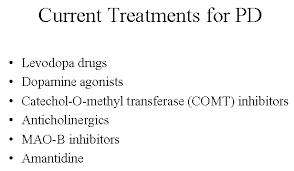

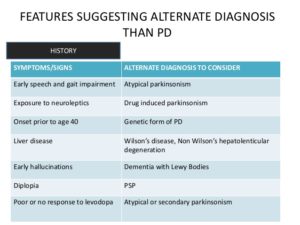

Medications are commonly used to increase the levels of dopamine in the brain of patients with Parkinson’s disease in an attempt to slow down the progression of the disease. Dopaminergic agents remain the principal treatments for patient with Parkinson’s disease, such as Levodopa and Dopaminergic agonist. In many patients, however, a combination of relatively resistant motor symptoms, motor complications such as dyskinesias or non-motor symptoms such as dysautonomia may lead to substantial disability in spite of dopaminergic therapy. In recent days, there has been an increasing interest in agents targeting non-motor symptoms, such as dementia and sleepiness.

As patients with Parkinson’s disease live longer and acquire additional comorbidities, addressing these non-motor symptoms has become increasingly important. Among anti-depressants, Amitriptiline and SSRI are commonly used, while Rivastigmine became the first FDA approved medication for the treatment of dementia associated with PD.

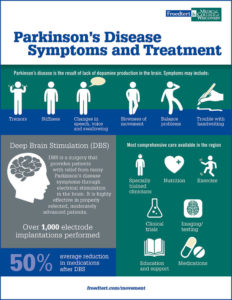

SURGERY: Surgery for Parkinson’s disease has come a long way since it was first developed more than 50 years ago. The newest version of this surgery, deep brain stimulation (DBS), was developed in the 1990s and is now a standard treatment. Worldwide, about 30,000 people have had deep brain stimulation.

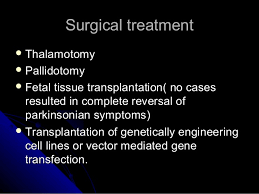

Lifestyle modifications have been shown to be effective for controlling motor symptoms in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease. The surgical treatment options available for Parkinson’s patients with severe motor symptoms are pallidotomy, thalamotomy and Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS).

The novel approaches for treatment of Parkinson’s disease that are currently under investigation include neuroprotective therapy, foetal cell transplantation, and gene therapy.

What is Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) as a treatment?

DBS was introduced two decades ago and has gained widespread popularity as a surgical treatment for medically refractory Parkinson’s disease. DBS is a reversible procedure that has advantage over surgical lesioning (pallidotomy) and unilateral brain stimulation. DBS is comparable in efficacy to unilateral surgical lesioning7 while bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation is superior to pallidotomy. DBS is FDA approved for the treatment of medically refractory Parkinson’s disease and ET. DBS has proven its efficacy in the treatment of cardinal motor features of Parkinson’s disease such as bradykinesia, tremor and rigidity and it is unresponsive for non-motor symptoms such as cognition, speech, gait disturbance, mood and behaviour. Long-term studies have demonstrated that many of these effects last for long as long as levodopa responsiveness in maintained

During deep brain stimulation surgery, electrodes are inserted into the targeted brain region using MRI and neurophysiological mapping to ensure that they are implanted in the right place. A device called an impulse generator or IPG (similar to a pacemaker) is implanted under the collarbone to provide an electrical impulse to a part of the brain involved in motor function. Those who undergo the surgery are given a controller, which allows them to check the battery and to turn the device on or off. An IPG battery lasts for about three to five years and is relatively easy to replace under local anesthesia.

Is DBS Right for Me?

Although DBS is certainly the most important therapeutic advancement since the development of levodopa, it is not for every person with Parkinson’s. It is most effective – sometimes, dramatically so – for individuals who experience disabling tremors, wearing-off spells and medication-induced dyskinesias.

Deep brain stimulation is not a cure for Parkinson’s, and it does not slow disease progression. Like all brain surgery, deep brain stimulation surgery carries a small risk of infection, stroke, or bleeding. A small number of people with Parkinson’s have experienced cognitive decline after this surgery. That said, for many people, it can dramatically relieve some symptoms and improve quality of life. Studies show benefits lasting at least five years.

Gamma Knife radiosurgery

Gamma Knife radiosurgery is a painless procedure that uses hundreds of highly focused radiation beams to target deep brain regions to create precise functional lesions within the brain, with no surgical incision. Gamma Knife may be a treatment option for patients with Parkinson’s tremor who are high risk for surgery due to medical conditions or advanced age.

As the nation’s leading provider of Gamma Knife procedures, UPMC has treated more than 12,000 patients with tumors, vascular malformations, pain, and other functional problems.

It is very important that a person with Parkinson’s who is thinking of treatment from meds to surgery to possiby Gamma Knife radiosurgery be well informed about the procedures and realistic in his or her expectations. This means there’s no standard treatment for the disease – the treatment for each person with Parkinson’s is based on his or her symptoms.

Advanced treatments

MRI-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) is a minimally invasive treatment that has helped some people with Parkinson’s disease manage tremors. Ultrasound is guided by an MRI to the area in the brain where the tremors start. The ultrasound waves are at a very high temperature and burn areas that are contributing to the tremors.

Remember Parkinson’s disease can’t be cured, but medications can help control the symptoms, often dramatically. In some more advanced cases, surgery may be advised.

Your health care provider may also recommend lifestyle changes, especially ongoing aerobic exercise.

In some cases, physical therapy that focuses on balance and stretching is important.

A speech-language pathologist may help improve speech problems.

There is always support groups for Parkinson’s Disease for patients diagnosed with it and the family involved also!