The environment

Take our environment, there’s a caustic substance common to our environment whose very presence turns iron into brittle rust, dramatically increases the risk of fire and explosion, and sometimes destroys the cells of the very organisms that depend on it for survival. This substance that makes up 21% of our atmosphere is Diatomic oxygen (O2), more widely know as just oxygen.

Oxygen picture————————————————

The appearance of free oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere led to the Great Oxidation Event. This was triggered by cyanobacteria producing oxygen that was used by multi-cellular forms as early as 2.3 billion years ago. As evolutionary biologists from the Universities of Zurich and Gothenburg have shown, this multiple cellularity was linked to the rise in oxygen and thus played a significant role for life on Earth as it is today.

Cyanobacteria belong to Earth’s oldest organisms. They are still present today in oceans and waters and even in hot springs. By producing oxygen and evolving into multicellular forms, they played a key role in the emergence of organisms that breathe oxygen. This has, now, been demonstrated by a team of scientists under the supervision and instruction of evolutionary biologists from the University of Zurich. According to their studies, cyanobacteria developed multicellularity around one billion years earlier than eukaryotes — cells with one true nucleus. At almost the same time as multi-cellular cyanobacteria appeared, a process of oxygenation began in the oceans and in Earth’s atmosphere.

Multi-cellularity as early as 2.3 billion years ago

The scientists analyzed the phylogenies of living cyanobacteria and combined their findings with data from fossil records for cyanobacteria. According to the results recorded by Bettina Schirrmeister and her colleagues, multi-cellular cyanobacteria emerged much earlier than previously assumed. “Multi-cellularity developed relatively early in the history of cyanobacteria, more than 2.3 billion years ago,” Schirrmeister explains in her doctoral thesis, written at the University of Zurich.

Link between multicellularity and the Great Oxidation Event

According to the scientists, multicellularity developed shortly before the rise in levels of free oxygen in the oceans and in the atmosphere. This accumulation of free oxygen is referred to as the Great Oxidation Event, and is seen as the most significant climate event in Earth’s history. Based on their data, Schirrmeister and her doctoral supervisor Homayoun Bagheri believe that there is a link between the emergence of multi-cellularity and the event. According to Bagheri, multi-cellular life forms often have a more efficient metabolism than unicellular forms. The researchers are thus proposing the theory that the newly developed multi-cellularity of the cyanobacteria played a role in triggering the Great Oxidation Event.

Cyanobacteria occupied free niches

The increased production of oxygen set Earth’s original atmosphere off balance. Because oxygen was poisonous for large numbers of anaerobic organisms, many anaerobic types of bacteria were eliminated, opening up ecological ‘niches’. The researchers have determined the existence of many new types of multi-cellular cyanobacteria subsequent to the fundamental climatic event, and are deducing that these occupied the newly developed habitats. “Morphological changes in microorganisms such as bacteria were able to impact the environment fundamentally and to an extent scarcely imaginable,” concludes Schirrmeister.

Water oxygenation:

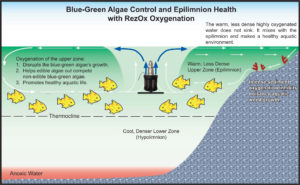

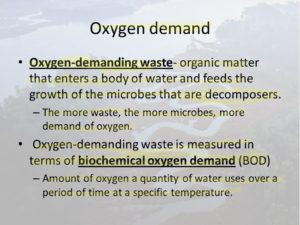

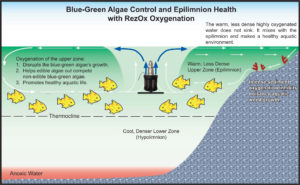

Water aeration is often required in water bodies that suffer from anoxic conditions, usually caused by adjacent human activities such as sewage discharges, agricultural run-off, or over-baiting a fishing lake. Aeration can be achieved through the infusion of air into the bottom of the lake, lagoon or pond or by surface agitation from a fountain or spray-like device to allow for oxygen exchange at the surface and the release of noxious gasses such as carbon dioxide, methane or hydrogen sulfide.

Dissolved oxygen (DO) is a major contributor to water quality. Not only do fish and other aquatic animals need it, but oxygen breathing aerobic bacteria decompose organic matter. When oxygen concentrations become low, anoxic conditions may develop which can decrease the ability of the water body to support life.

Surface aeration-Fountains aerate by pulling water from the surface of the water (usually the first 1–2 feet) and propelling it into the air. Some fountains incorporate the use of a draft tube, which extends deeper and is able to pull water from approximately six feet below the surface, so as to achieve more water circulation. Fountains are a popular method of surface aerators because of the aesthetic appearance that they offer. However, most fountains are unable to produce a large area of oxygenated water. Also, running electricity through the water to the fountain can be a safety hazard. Fountains help circulate water in oxygenation, of course to a limited degree.

Diffused aeration systems utilize bubbles to aerate as well as mix the water. Water displacement from the expulsion of bubbles can cause a mixing action to occur, and the contact between the water and the bubble will result in an oxygen transfer.

Coarse bubble aeration is a type of subsurface aeration wherein air is pumped from an on-shore air compressor, through a hose to a unit placed at the bottom of the water body. The unit expels coarse bubbles (more than 2mm in diameter), which release oxygen when they come into contact with the water, which also contributes to a mixing of the lake’s stratified layers.

Fine bubble aeration is an efficient way to transfer oxygen to a water body. A compressor on shore pumps air through a hose, which is connected to an underwater aeration unit.

Lake destratification Is using circulators that are commonly used to mix a pond or lake and thus reduce thermal stratification. Once circulated water reaches the surface, the air-water interface facilitates the transfer of oxygen to the lake water.

Oxygenation Barges During heavy rain, London’s sewage storm pipes overflow into the River Thames, sending dissolved oxygen levels plummeting and threatening the species it supports.[14] Two dedicated McTay Marine vessels, oxygenation barges Thames Bubbler and Thames Vitality are used to replenish oxygen levels, as part of an ongoing battle to clean up the river, which now supports 115 species of fish and hundreds more invertebrates, plants and birds.

The Smithsonian states the Earth has a surprising new player in the climate game: oxygen. Even though oxygen is not a heat-trapping greenhouse gas, its concentration in our atmosphere can affect how much sunlight reaches the ground, and new models suggest that effect has altered climate in the past. Greenhouse gases = too much of one thing. Human activity increases the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere—mainly carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas). The extra greenhouse gas may be trapping much heat, abnormally raising Earth’s temperatures. Human activity increases the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere—mainly carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). The extra greenhouse gas may be trapping too much heat, abnormally raising Earth’s temperatures. Human activity increases the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere—mainly carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). The extra greenhouse gas may be trapping too much heat, abnormally raising Earth’s temperatures. Human activity increases the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere—mainly carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). The extra greenhouse gas may be trapping too much heat, abnormally raising Earth’s temperatures. Human activity increases the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere—mainly carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). The extra greenhouse gas may be trapping too much heat, abnormally raising Earth’s temperatures.

Oxygen currently makes up about 21 percent of the gases in the planet’s atmosphere, but that level hasn’t been steady over Earth’s history. For the first couple of billion years, there was the little oxygen in the atmosphere. Then, about 2.5 billion years ago, oxygen started getting added to the atmosphere by photosynthetic cyanobacteria. That waste product sparked the mass extinction known as the Great Oxygenation Event (explained above). But over time, new forms of life evolved that use or expel oxygen in respiration, and atmospheric oxygen levels continued to increase. “The production and burial of plant matter over long periods causes oxygen levels to rise,” explains Poulsen.

Levels can fall again when that trapped ancient organic matter becomes exposed on land, and elements such as iron react with oxygen from the atmosphere, a reaction called oxidative weathering. As a result of these processes, atmospheric oxygen levels have varied from a low of 10 percent to a high of 35 percent over the last 540 million years or so.

Poulsen and his colleagues were studying the climate and plants of the late Paleozoic, and during a meeting they started talking about whether oxygen levels might somehow have affected climate in the past. Studies have shown that atmospheric carbon dioxide has been the main climate driver through deep time, so most thought oxygen’s role has been negligible but we have to live which is breathing 02 and the ending result CO2 when we expire and surely need oil & natural gas to some extent even if we went on energy for all our electricity and cars. Remember everything has a beginning and an ending, with wear and tear done to it at the end.

Highly concentrated sources of oxygen promote rapid combustion and therefore are fire and explosion hazards in the presence of fuels. The fire that killed the Apollo 1 crew on a test launchpad spread so rapidly because the pure oxygen atmosphere was at normal atmospheric pressure instead of the one third pressure that would be used during an actual launch.

Oxygen regarding metals:

Rust is another name for iron oxide, which occurs when iron or an alloy that contains iron, like steel, is exposed to oxygen and moisture for a long period of time. Over time, the oxygen combines with the metal at an atomic level, forming a new compound called an oxide and weakening the bonds of the metal itself. Although some people refer to rust generally as “oxidation,” that term is much more general; although rust forms when iron undergoes oxidation, not all oxidation forms rust. Only iron or alloys that contain iron can rust, but other metals can corrode in similar ways.

The main catalyst for the rusting process is water. Iron or steel structures might appear to be solid, but water molecules can penetrate the microscopic pits and cracks in any exposed metal. The hydrogen atoms present in water molecules can combine with other elements to form acids, which will eventually cause more metal to be exposed.

If sodium is present, as is the case with saltwater, the corrosion is likely to occur more quickly. Meanwhile, the oxygen atoms combine with metallic atoms to form the destructive oxide compound. As the atoms combine, they weaken the metal, making the structure brittle and crumbly.

Some pieces of iron or steel are thick enough to maintain their integrity even if iron oxide forms on the surface. The thinner the metal, the better the chance that rusting will occur. Placing a steel wool pad in water and exposing it to air will cause rusting to begin almost immediately because the steel filaments are so thin. Eventually, the individual iron bonds will be destroyed, and the entire pad will disintegrate.

Rust formation cannot be stopped easily, but metals can be treated to resist the most damaging effects. Some are protected by water-resistant paints, preventative coatings or other chemical barriers, such as oil. It also is possible for one to reduce the chances of rust forming by using a dehumidifier or desiccant to help remove moisture from the air, but this usually is effective only in relatively small areas.

Steel is often galvanized to prevent iron oxide from forming; this process usually involves a very thin layer of zinc being applied to the surface. Another process, called plating, can be used to add a layer of zinc, tin or chrome to the metal. Cathodic protection involves using an electrical charge to suppress or prevent the chemical reaction that causes rust from occurring.

Quite interesting about oxygen and its interaction capabilities!