Auto brewery syndrome is a rare condition in which your body turns sugary and starchy foods into alcohol. This can cause symptoms as if you were drunk, even if you haven’t had any alcohol.

Auto-brewery syndrome or gut fermentation syndrome is a condition in which ethanol is produced through endogenous fermentation by fungi or bacteria in the gastrointestinal system, oral cavity, or urinary system. Patients with auto-brewery syndrome present with many of the signs and symptoms of alcohol intoxication while denying an intake of alcohol and often report a high-sugar, high-carbohydrate diet.

The production of endogenous ethanol occurs in minute quantities as part of normal digestion, but when fermenting yeast or bacteria become pathogenic, extreme blood alcohol levels may result. Auto-brewery syndrome is more prevalent in patients with co-morbidities such as diabetes, obesity, and Crohn disease but can occur in otherwise healthy individuals. Several strains of fermenting yeasts and rare bacteria are identified as pathogens. While auto-brewery syndrome is rarely diagnosed, it is probably underdiagnosed. Even rarer are two cases of auto-brewery syndrome identified, one in the oral cavity and one in the urinary bladder.

ETIOLOGY:

Various yeasts from the Candida and Saccharomyces families are commensals turned pathogenic that cause auto-brewery syndrome. Several strains of bacteria are also known to ferment ethanol.

-

Fermenting yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, S. boulardii, and various strains of Candida, including C. glabrata, C. albicans, C. kefyr, and C. parapsilosis are identified as causes of this condition.

-

The bacteria Klebsiella pneumonia, Enterococcus faecium, E. faecalis, and Citrobacter freundii are implicated in at least one case each.

-

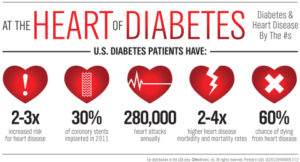

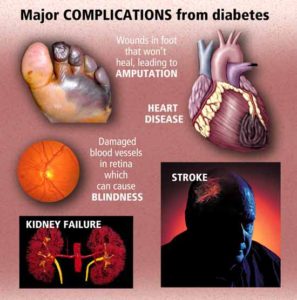

Existing conditions, such as diabetes or liver problems, can impact the diagnosis of ABS. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) or liver cirrhosis (LC) tested higher for endogenous ethanol (EnEth) levels than a control group without the disease. But the EnEth levels peaked highest in a group of patients with both type 2 DM and LC, where the blood alcohol concentration reached 22.3 mg/dL.

-

Four common yeasts (Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Torulopsis glabrata) were combined with infant formulas. Ethanol production was measured after 24 and 48 hours. The quantities of ethanol produced suggest an explanation for patients exhibiting auto-brewery syndrome.

-

Bacterial production of EnEth is involved in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Higher levels of EnEth are also detected in obese patients and those with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

SYMPTOMS:

Auto brewery syndrome can make you:

- drunk without drinking any alcohol

- very drunk after only drinking a small amount of alcohol (such as two beers)

Symptoms and side effects are similar to when you are slightly drunk or when you have a hangover from drinking too much:

- red or flushed skin

- dizziness

- disorientation

- headache pain

- nausea and vomiting

- dehydration

- dry mouth

- burping or belching

- fatigue

- memory and concentration problems

- mood changes

Auto brewery syndrome can also lead to or worsen other health conditions such as:

- chronic fatigue syndrome

- irritable bowel syndrome

- depression and anxiety

How does someone get this syndrome?

Adults and children can have auto brewery syndrome. Signs and symptoms are similar in both. Auto brewery syndrome is usually a complication of another disease, imbalance, or infection in the body.

You can’t be born with this rare syndrome. However, you may be born with or get another condition that triggers auto brewery syndrome. For example, in adults, too much yeast in the gut may be caused by Crohn’s disease. This can set off auto brewery syndrome.

In some people liver problems may cause auto brewery syndrome. In these cases, the liver isn’t able to clear out alcohol fast enough. Even a small amount of alcohol made by gut yeast leads to symptoms.

Toddlers and children with a condition called short bowel syndrome have a higher chance of getting auto brewery syndrome. A medical case reported that a 3-year-old girl Trusted Source with short bowel syndrome would get “drunk” after drinking fruit juice, which is naturally high in carbohydrates.

Other reasons you may have too much yeast in your body include:

- poor nutrition

- antibiotics

- inflammatory bowel disease

- diabetes

- low immune system

How its diagnosed:

There are no specific tests to diagnose auto brewery syndrome. This condition is still newly discovered and more research is needed. Symptoms alone are typically not enough for a diagnosis.

Your doctor will likely do a stool test to find out if you have too much yeast in your gut. This involves sending a tiny sample of a bowel movement to a lab to be tested. Another test that might be used by some doctors is the glucose challenge.

In the glucose challenge test, you’ll be given a glucose (sugar) capsule. You won’t be allowed to eat or drink anything else for a few hours before and after the test. After about an hour, your doctor will check your blood alcohol level. If you don’t have auto brewery syndrome your blood alcohol level will be zero. If you have auto brewery disease your blood alcohol level may range from 1.0 to 7.0 milligrams per deciliter.

If you suspect you have this auto brewery syndrome, you might try a similar test at home, though you shouldn’t use it to self-diagnose. Eat something sugary, like a cookie, on an empty stomach. After an hour use an at-home breathalyzer to see if your blood alcohol level has risen. Write down any symptoms.

This home test may not work because you may not have noticeable symptoms. At-home breathalyzers may also not be as accurate as the ones used by doctors and law enforcement. Regardless of what you observe, see a doctor for a diagnosis.