How Juvenile Arthritis (JIA) is Diagnosis:

Diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis can be difficult because joint pain can be caused by many different types of problems. No single test can confirm a diagnosis, but tests can help rule out some other conditions that produce similar signs and symptoms.

1. Blood tests

Some of the most common blood tests for suspected cases include:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). The sedimentation rate is the speed at which your red blood cells settle to the bottom of a tube of blood. An elevated rate can indicate inflammation. Measuring the ESR is primarily used to determine the degree of inflammation.

- C-reactive protein. This blood test also measures levels of general inflammation in the body but on a different scale than the ESR.

- Antinuclear antibody. Antinuclear antibodies are proteins commonly produced by the immune systems of people with certain autoimmune diseases, including arthritis. They are a marker for an increased chance of eye inflammation.

- Rheumatoid factor. This antibody is occasionally found in the blood of children who have juvenile idiopathic arthritis and may mean there’s a higher risk of damage from arthritis.

- Cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP). Like the rheumatoid factor, the CCP is another antibody that may be found in the blood of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and may indicate a higher risk of damage.

In many children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, no significant abnormality will be found in these blood tests.

2. Imaging scans

X-rays or magnetic resonance imaging may be taken to exclude other conditions, such as fractures, tumors, infection or congenital defects.

Imaging may also be used from time to time after the diagnosis to monitor bone development and to detect joint damage.

Juvenile Arthritis (JIA) Treatment:

Treatment for juvenile idiopathic arthritis focuses on helping your child maintain a normal level of physical and social activity. To accomplish this, doctors may use a combination of strategies to relieve pain and swelling, maintain full movement and strength, and prevent complications.

1. Medications

The medications used to help children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis are chosen to decrease pain, improve function and minimize potential joint damage.

Typical medications include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These medications, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve), reduce pain and swelling. Side effects include stomach upset and, much less often, kidney and liver problems.

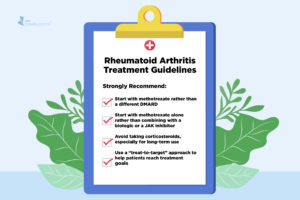

- Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Doctors use these medications when NSAIDs alone fail to relieve symptoms of joint pain and swelling or if there is a high risk of damage in the future.DMARDs may be taken in combination with NSAIDs and are used to slow the progress of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The most commonly used DMARD for children is methotrexate (Trexall, Xatmep, others). Side effects of methotrexate may include nausea, low blood counts, liver problems and a mild increased risk of infection.

- Biologic agents. Also known as biologic response modifiers, this newer class of drugs includes tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, such as etanercept (Enbrel, Erelzi, Eticovo), adalimumab (Humira), golimumab (Simponi) and infliximab (Remicade, Inflectra, others). These medications can help reduce systemic inflammation and prevent joint damage. They may be used with DMARDs and other medications.Other biologic agents work to suppress the immune system in slightly different ways, including abatacept (Orencia), rituximab (Rituxan, Truxima, Ruxience), anakinra (Kineret) and tocilizumab (Actemra). All biologics can increase the risk of infection.

- Corticosteroids. Medications such as prednisone may be used to control symptoms until another medication takes effect. They are also used to treat inflammation when it is not in the joints, such as inflammation of the sac around the heart.These drugs can interfere with normal growth and increase susceptibility to infection, so they generally should be used for the shortest possible duration.

2. Therapies

Your doctor may recommend that your child work with a physical therapist to help keep joints flexible and maintain range of motion and muscle tone.

A physical therapist or an occupational therapist may make additional recommendations regarding the best exercise and protective equipment for your child.

A physical or occupational therapist may also recommend that your child make use of joint supports or splints to help protect joints and keep them in a good functional position.

3. Surgery

In very severe cases, surgery may be needed to improve joint function.

***Parents or caregivers help limit the arthritis in your children by doing the following:

- Getting regular exercise. Exercise is important because it promotes both muscle strength and joint flexibility. Swimming is an excellent choice because it places minimal stress on joints.

- Applying cold or heat. Stiffness affects many children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, particularly in the morning. Some children respond well to cold packs, particularly after activity. However, most children prefer warmth, such as a hot pack or a hot bath or shower, especially in the morning

- Eating Well. Some children with arthritis have poor appetites. Others may gain excess weight due to medications or physical inactivity. A healthy diet can help maintain an appropriate body weight.Know adequate calcium in the diet is important because children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis are at risk of developing weak bones due to the disease, the use of corticosteroids, and decreased physical activity and weight bearing.