Today, many children who are born deaf or blind have access to amazing support to help them navigate the world. Similarly, those who suffer loss of hearing or sight later in life have numerous resources to help them overcome communication barriers introduced by their new reality. It’s unlikely that those in this situation would be cut off completely from communicating with others. In the 1880s, Helen Keller wasn’t so fortunate. Despite all of the barriers that she faced because of her deafness, her blindness and her gender, she was able to do impressive work with Anne Sullivan to move care of the deaf-blind population forward

Those unfortunately born with no sight and hearing face many challenges.

It may seem that deaf-blindness refers to a total inability to see or hear. However, in reality deaf-blindness is a condition in which the combination of hearing and visual losses in children cause “such severe communication and other developmental and educational needs that they cannot be accommodated in special education programs solely for children with deafness or children with blindness” ( 34 CFR 300.8 ( c ) ( 2 ), 2006) or multiple disabilities. Children who are called deaf-blind are singled out educationally because impairments of sight and hearing require thoughtful and unique educational approaches in order to ensure that children with this disability have the opportunity to reach their full potential.

A person who is deaf-blind has a unique experience of the world. For people who can see and hear, the world extends outward as far as his or her eyes and ears can reach. For the young child who is deaf-blind, the world is initially much narrower. If the child is profoundly deaf and totally blind, his or her experience of the world extends only as far as the fingertips can reach. Such children are effectively alone if no one is touching them. Their concepts of the world depend upon what or whom they have had the opportunity to physically contact.

If a child who is deaf-blind has some usable vision and/or hearing, as many do, her or his world will be enlarged. Many children called deaf-blind have enough vision to be able to move about in their environments, recognize familiar people, see sign language at close distances, and perhaps read large print. Others have sufficient hearing to recognize familiar sounds, understand some speech, or develop speech themselves. The range of sensory impairments included in the term “deaf-blindness” is great.

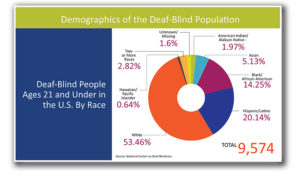

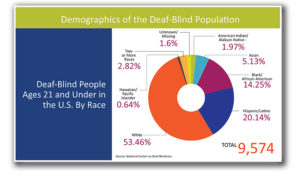

As far as it has been possible to count them, there are over 10,000 children (ages birth to 22 years) in the United States who have been classified as deaf-blind (NCDB, 2008). It has been estimated that the adult deaf-blind population numbers 35-40,000 (Watson, 1993). The causes of deaf-blindness are many. Below is a list of many of the possible etiologies of deaf-blindness.

Major Causes of Deaf-Blindness

Syndromes-Like Down Syndrome, Trisomy13 Syndrome & Usher

Multiple Congenital Anomalies- Like CHARGE Association, Fetal alcohol syndrome, Hydrocephaly, Maternal drug abuse and Microcephaly.

Prematurity=Congenital Prenatal Dysfunction. Like AIDS, Herpes, Rubella, Syphilis and Toxoplasmosis.

Post-natal Causes- Like Asphyxia, Encephalitis, Head injury/trauma, Meningitis and Stroke.

The one major CHALLENGE these patients face:

Communication

The disability of deaf-blindness presents unique challenges to families, teachers, and caregivers, who must make sure that the person who is deaf-blind has access to the world beyond the limited reach of his or her eyes, ears, and fingertips. The people in the environment of children or adults who are deaf-blind must seek to include them—moment-by-moment—in the flow of life and in the physical environments that surround them. If they do not, the child will be isolated and will not have the opportunity to grow and to learn. If they do, the child will be afforded the opportunity to develop to his or her fullest potential.

The most important challenge for parents, caregivers, and teachers is to communicate meaningfully with the child who is deaf-blind. Continual good communication will help foster his or her healthy development. Communication involves much more than mere language. Good communication can best be thought of as conversation. Conversations employ body language and gestures, as well as both signed and spoken words. A conversation with a child who is deaf-blind can begin with a partner who simply notices what the child is paying attention to at the moment and finds a way to let the child know that his or her interest is shared.

This shared interest, once established, can become a topic around which a conversation can be built. Mutual conversational topics are typically established between a parent and a sighted or hearing child by making eye contact and by gestures such as pointing or nodding, or by exchanges of sounds and facial expressions. Lacking significant amounts of sight and hearing, children who are deaf-blind will often need touch in order for them to be sure that their partner shares their focus of attention. The parent or teacher may, for example, touch an interesting object along with the child in a nondirective way. Or, the mother may imitate a child’s movements, allowing the child tactual access to that imitation, if necessary. (This is the tactual equivalent of the actions of a mother who instinctively imitates her child’s babbling sounds.) Establishing a mutual interest like this will open up the possibility for conversational interaction.

Teachers, parents, siblings, and peers can continue conversations with children who are deaf-blind by learning to pause after each turn in the interaction to allow time for response. These children frequently have very slow response times. Respecting the child’s own timing is crucial to establishing successful interactions. Pausing long enough to allow the child to take another turn in the interaction, then responding to that turn, pausing again, and so on—this back-and-forth exchange becomes a conversation. Such conversations, repeated consistently, build relationships and become the eventual basis for language learning.

As the child who is deaf-blind becomes comfortable interacting nonverbally with others, she or he becomes ready to receive some form of symbolic communication as part of those interactions. Often it is helpful to accompany the introduction of words (spoken or signed) with the use of simple gestures and/or objects which serve as symbols or representations for activities. Doing so may help a child develop the understanding that one thing can stand for another, and will also enable him or her to anticipate events.

Think of the many thousands of words and sentences that most children hear before they speak their own first words. A child who is deaf-blind needs comparable language stimulation, adjusted to his or her ability to receive and make sense of it. Parents, caregivers, and teachers face the challenge of providing an environment rich in language that is meaningful and accessible to the child who is deaf-blind. Only with such a rich language environment will the child have the opportunity to acquire language herself or himself. Those around the child can create a rich language environment by continually commenting on the child’s own experience using sign language, speech, or whatever symbol system is accessible to the child. These comments are best made during conversational interactions. A teacher or a parent may, for example, use gesture or sign language to name the object that he or she and the child are both touching, or name the movement that they share. This naming of objects and actions, done many, many times, may begin to give the child who is deaf-blind a similar opportunity afforded to the hearing child—that of making meaningful connections between words and the things for which they stand.

Principal communication systems for persons who are deaf-blind are these:

- touch cues

- gestures

- object symbols

- picture symbols

- sign language

- fingerspelling

- Signed English

- Pidgin Signed English

- braille writing and reading

- Tadoma method of speech reading

- American Sign Language

- large print writing and reading

- lip-reading speech

Along with nonverbal and verbal conversations, a child who is deaf-blind needs a reliable routine of meaningful activities, and some way or ways that this routine can be communicated to her or him. Touch cues, gestures, and use of object symbols are some typical ways in which to let a child who is deaf-blind know what is about to happen to her or him. Each time before the child is picked up, for example, the caregiver may gently lift his or her arms a bit, and then pause, giving the child time to ready herself or himself for being handled. Such consistency will help the child to feel secure and to begin to make the world predictable, thus allowing the child to develop expectations. Children and adults who are deaf-blind and are able to use symbolic communication may also be more reliant on predictable routine than people who are sighted and hearing. Predictable routine may help to ease the anxiety which is often caused by the lack of sensory information.

Stay tune for Part II tomorrow on other challenges.