1-MRSA Infection

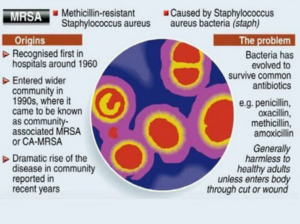

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), also known as multidrug resistant S. aureus, includes any strain of S. aureus that has become resistant to the group of antibiotics known as beta-lactam antibiotics. Included in this group are the penicillins (methicillin, amoxicillin, oxacillin) and cephalosporins. Staphylococcus aureus includes gram-positive, nonmotile, non-spore-forming cocci that can be found alone, in pairs, or in grapelike clusters.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

When penicillin was first introduced in the early 1940s, it was considered to be a wonder drug because it reduced the death rate from Staphylococcus infection from 70% to 25%. Unfortunately, by 1944, drug resistance was beginning to occur, so methicillin was synthesized, and, in 1959, it became the world’s first semisynthetic penicillin. Shortly thereafter in 1961, staphylococcal resistance to methicillin began as well, and the name “methicillin-resistant S. aureus” and the acronym MRSA were coined. Although methicillin was discontinued in 1993, the name and acronym have remained because of MRSA history.

MRSA is now the most common drug-resistant infection acquired in healthcare facilities. In addition to becoming more problematic as a top HAI in recent years, transmission of MRSA has also become more common in children, prison inmates, and sports participants. Community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) most often presents in the form of skin infections (see Figure 5). Hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA) infections manifest in various forms, including bloodstream infections, surgical site infections, and pneumonia. Although approximately 25–30% of persons are colonized in the nasal passages with Staphylococcus, less than 2% are colonized with MRSA.

MRSA are extremely resistant and can survive for weeks on environmental surfaces. Transfer of the pathogen can occur directly from patient contact with a contaminated surface or indirectly as healthcare workers touch contaminated surfaces with gloves or hands and then touch a patient.

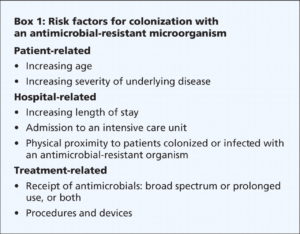

Risk factors for healthcare-acquired MRSA infection include advanced age, young age, use of quinolone antibiotics, and extended stay in a healthcare facility. Those with diabetes, cancer, or a compromised immune system are also at increased risk of infection.

Symptoms of MRSA infection vary depending on the type and stage of infection and the susceptibility of the organism. Skin infections may appear as painful, red, swollen pustules or boils; as cellulitis; or as a spider bite or bump. They can be found in areas where visible skin trauma has occurred or in areas covered by hair. Patients may also have fever, headaches, hypotension, and joint pain. Complications of MRSA-related skin infections include endocarditis, necrotizing fasciitis, osteomyelitis, and sepsis.

Patient history of admission to a healthcare facility is useful in diagnosing HA-MRSA. Definitive diagnosis of MRSA is made by oxacillin/methicillin resistance that is shown by lab culture and susceptibility testing. Specimens submitted for testing vary depending on the site of suspected infection and may include tissue, wound drainage, sputum, respiratory secretions, and blood or urine cultures.

Treatment for MRSA infections varies based on site of infection, stage of infection, and age of the individual. Treatment includes drainage of abscesses, surgical debridement, decolonization strategies, and antimicrobial therapy with antibiotics such as vancomycin #1 in alot of cases, clindamycin, daptomycin, linezolid, rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), quinupristin-dalfopristin, telavancin, and tetracyclines (limited use). MRSA is rapidly becoming resistant to rifampin; therefore, this drug should not be used alone in the treatment of MRSA infections. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is recommended for treatment of severe MRSA infections.

The CDC recommends healthcare personnel follow these guidelines to help prevent MRSA infections:

- Follow procedures to recognize previously colonized and infected patients.

- Follow appropriate hand hygiene practices and isolation precautions (see discussion on hand hygiene and isolation precautions later in this course). The CDC has not made a recommendation on when to discontinue contact precautions. Healthcare workers should check with their individual institution’s infection control policies.

- Place patients in single rooms, or, if a single room is not available, cohort patients with the same MRSA in the same room or in the same patient care area. If cohorting patients with the same MRSA is not possible, place MRSA patients in rooms with patients who are at low risk for acquisition of MRSA and are likely to have short lengths of stay.

- Keep skin wounds of MRSA patients clean and covered until healed.

- Handle equipment and instruments/devices used for MRSA patients appropriately, with care and attention to disinfection according to institution infection control policy. Ensure that equipment is properly cleaned and disinfected before being used with another patient.

2-VancoResistantEnterococci

Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Infection (VRE)

Enterococci (formerly known as Group D streptococci) are non-spore-forming, gram-positive cocci that exist in either pairs or short chains. They are commonly found in the human intestine or the female genital tract. The most common organism associated with vancomycin-ressistant enterococci (VRE) infection in hospitals is Enterococcus faecium. Enterococcus faecalis is also a cause of human disease. VRE infections can occur in the urinary tract, in wounds associated with catheters, in the bloodstream, and in surgical sites. Enterococci are a common cause of endocarditis, intra-abdominal infections, and pelvic infections.

VRE was first reported in Europe in 1986, followed in 1989 by the first report in the United States. Since then it has spread rapidly. Between 1990 and 1997, the prevalence of VRE in hospital patients increased from less than 1% to 15%.

VRE, which is found predominantly in hospitalized or recently hospitalized patients, are difficult to eliminate because they are able to withstand extreme temperatures, can survive for long periods on environmental surfaces, and are resistant to vancomycin. Transmission of VRE occurs most commonly in the form of person-to-person contact by the hands of healthcare workers after contact with the blood, urine, or feces an infected individual. VRE is also spread from contact with environmental surfaces, or through contact with the open wound of an infected person.

People most at risk for infection with VRE include the elderly and those with diabetes, those with compromised immune systems, and those who are already colonized with the bacteria. Prolonged hospitalization, catheterization (urinary and intravenous), and long-term use of vancomycin or other antibiotics also increase a person’s risk of infection.

Symptoms of VRE infection vary depending on the site of infection and may include erythema, warmth, edema, fever, abdominal pain, pelvic pain, and organ pain. Definitive diagnosis is made by culture and susceptibility testing with specimens obtained from suspected sites of infection. Treatment of VRE infection may include drainage of abscesses; removal of prosthetic devices, IV lines, or catheters; and antibiotic therapy with one or more appropriate antibiotics that show activity against VRE. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is recommended for treatment of patients with serious infections or VRE that is resistant to other antibiotics.

To prevent infection from VRE, the CDC recommends healthcare professionals use vancomycin prudently and promptly detect and report VRE infections. Healthcare providers in direct contact with patients should follow steps for proper hand hygiene and contact precautions.