One pattern stood out pretty clearly: Lethal violence increased over the course of mammal evolution. While only about 0.3 percent of all mammals die in conflict with members of their own species, that rate is sixfold higher, or about 2 percent, for primates. Early humans likewise should have about a 2 percent rate—and that lines up with evidence of violence in Paleolithic human remains.

The medieval period was a particular killer, with human-on-human violence responsible for 12 percent of recorded deaths. But for the last century, we’ve been relatively peaceable, killing one another off at a rate of just 1.33 percent worldwide. And in the least violent parts of the world today, we enjoy homicide rates as low as 0.01 percent.

“Evolutionary history is not a total straitjacket on the human condition; humans have changed and will continue to change in surprising ways,” says study author José María Gómez of Spain’s Arid Zones Experimental Station. “No matter how violent or pacific we were in the origin, we can modulate the level of interpersonal violence by changing our social environment. We can build a more pacific society if we wish.”

Lethal Lemurs

What may be most surprising to some of us, though, isn’t how violent we are, but rather how we compare to our mammalian cousins.

It’s not easy to estimate how often animals kill each other in the wild, but Gómez and his team got a good overview of the species most and least likely to kill their own kind. The number of hyenas killed by other hyenas is around 8 percent. The yellow mongoose? Ten percent. And lemurs—cute, bug-eyed lemurs? As many as 17 percent of deaths in some lemur species result from lethal violence. (See “Prairie Dogs Are Serial Killers That Murder Their Competition.”)

Yet consider this: The study shows that 60 percent of mammal species are not known to kill one another at all, as far as anyone has seen. Very few bats (of more than 1,200 species) kill each other. And apparently pangolins and porcupines get along fine without offing members of their own species.

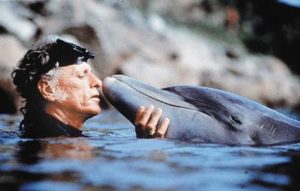

Whales are also generally thought not to kill their own kind. But dolphin biologist Richard Connor of the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth notes that a dolphin infanticide attempt was documented recently, and he cautions that whales, as their close relations, might also be more violent than we’ve thought.

“We could witness a lethal fight in dolphins but not know it, because the victim swims away apparently unimpaired, but is bleeding to death internally,” he says.

More often, though, people think animals are more violent than they really are, says animal behavior expert Marc Bekoff, an emeritus professor at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“Violence might be deep in the human lineage, but I think people should be very cautious in saying that when humans are violent, they’re behaving like nonhuman animals,” Bekoff says.

Bekoff has long contended that nonhumans are predominantly peaceful, and he points out that just as some roots of violence can be found in our animal past, so can roots of altruism and cooperation. He cites the work of the late anthropologist Robert Sussman, who found that even primates, some of the most aggressive mammals, spend less than one percent of their day fighting or otherwise competing.

After all, challenging another animal to a duel is risky, and for many animals the benefits don’t outweigh the risk of death. Highly social and territorial animals are the most likely to kill one another, the new study found. Many primates fit that killer profile, though as experts point out, not all of them. Bonobos have mostly peaceable, female-dominated social structures, while chimps are much more violent.

These differences among primates matter, says Richard Wrangham, a biological anthropologist at Harvard known for his study of the evolution of human warfare. In chimpanzees and other primates that kill each other, infanticide is the most common form of killing. But humans are different—they frequently kill each other as adults.

“That ‘adult-killing club’ is very small,” he says. “It includes a few social and territorial carnivores such as wolves, lions, and spotted hyenas.”

While humans may be expected to have some level of lethal violence based on their family tree, it would be wrong to conclude that there’s nothing surprising about human violence, Wrangham says.

When it comes to murderous tendencies, he says, “humans really are exceptional.” It appears expected with the reason irrational more for the human than animals. Animals primarily do it for protection, food but some animals do it just to kill at times, like Bamboon’s. Know most animals don’t kill for that reason.

Sad about this whole article is humans are considered the most intelligent creature on Earth, yet we kill our own species!