KNOW THE DIFFERENCE!

KNOW THE DIFFERENCE!

You’ve had stomach cramps for weeks, you’re exhausted and losing weight, and you keep having to run to the bathroom. What’s going on?

It could be an inflammatory bowel disease

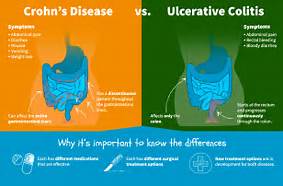

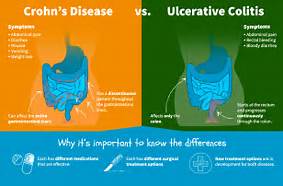

But which one? There are two: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. They have a lot in common, including long-term inflammation in your digestive system. But they also have some key differences that affect treatment.

The differences between both:

1.) The area of the intestines it effects:

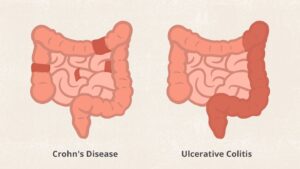

Ulcerative colitis affects only the inner lining of the colon, also called the large intestine. But in Crohn’s disease, inflammation can appear anywhere in the digestive tract, from the mouth to the anus. And it generally affects all the layers of the bowel walls, not just the inner lining.

By the way, if you hear some people just say “colitis ,” that’s not the same thing. It means inflammation of the colon. With “ulcerative colitis,” you have sores (ulcers) in the lining of your colon, as well as inflammation there.

2.) Where the inflammation is.

People with Crohn’s disease often have healthy areas in between inflamed spots. But with UC, the affected area isn’t interrupted.

Similar Features of Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are:

- Both diseases often develop in teenagers and young adults although the disease can occur at any age

- Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease affect men and women equally

- The symptoms of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are very similar

- The causes of both UC and Crohn’s disease are not known and both diseases have similar types of contributing factors such as environmental, genetic and an inappropriate response by the body’s immune system.

Colitis refers to inflammation of the inner lining of the colon. There are numerous causes of colitis including infection, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), ischemic colitis, allergic reactions, and microscopic colitis.

All colitis means in medical terminology is Col=colon with itis=swelling so put together colitis=inflammed colon. Now there are different causes for inflammed colon, one being Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) or Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)and don’t mix IBD with IBS.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an umbrella term used to describe disorders that involve chronic inflammation of your digestive tract. Types of IBD include:

- Ulcerative colitis. This condition causes long-lasting inflammation and sores (ulcers) in the innermost lining of your large intestine (colon) and rectum.

- Crohn’s disease. This type of IBD is characterized by inflammation of the lining of your digestive tract, which often spreads deep into affected tissues.

Both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease both usually involve severe diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue and weight loss.

Part I

What is ulcerative colitis actually?

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) distinguished by inflammation of the large intestine (rectum and colon). The innermost lining of the large intestine becomes inflamed, and ulcers may form on the surface. UC can also affect:

- Limited to the large intestine (colon and rectum)

- Occurs in the rectum and colon, involving a part or the entire colon

- Appears in a continuous pattern

- Inflammation occurs in innermost lining of the intestine

- About 30% of people in remission will experience a relapse in the next year

Ulcerative colitis usually affects only the innermost lining of your large intestine (colon) and rectum. It occurs only through continuous stretches of your colon, unlike Crohn’s disease which occurs in patches anywhere in the digestive tract and often spreads deep into the layers of affected tissues.

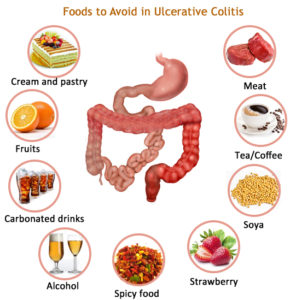

UC is like any other disease people may get…they may just get it. You don’t get it from eating something bad, like your friend but eating something bad may exacerbate the symptoms if you eat bad food. Eating bad food will not cause you to get the disease UC.

Ulcerative colitis symptoms can include: Abdominal pain/discomfort, Blood or pus in stool, Fever, Weight loss, Frequent recurring diarrhea. Fatigue, Reduced appetite, and Tenesmus: A sudden and constant feeling that you have to move your bowels.

Mild ulcerative colitis:

- Up to 4 loose stools per day

- Stools may be bloody

- Mild abdominal pain

Moderate ulcerative colitis:

- 4-6 loose stools per day

- Stools may be bloody

- Moderate abdominal pain

- Anemia

Severe ulcerative colitis:

- More than 6 bloody loose stools per day

- Fever, anemia, and rapid heart rate

Very Severe ulcerative colitis (Fulminant):

- More than 10 loose stools per day

- Constant blood in stools

- Abdominal tenderness/distention

- Blood transfusion may be a requirement

- Potentially fatal complications

When discussing your UC with your doctor, it is important that you have an open and honest conversation about your symptoms, since your doctor will use that information to help decide what treatment plan is appropriate for you.

How is Ulcerative Colitis Treated:

Ulcerative colitis treatment usually involves either medication therapy or surgery.

Several categories of medications may be effective in treating ulcerative colitis. The type you take will depend on the severity of your condition. The medications that work well for some people may not work for others. It may take time to find a medication that helps you.

In addition, because some medications have serious side effects, you’ll need to weigh the benefits and risks of any treatment.

There are anti-inflammatory medications involved and are often the first step in the treatment of ulcerative colitis and are appropriate for most people with this condition This would include:

- 5-aminosalicylates. Examples of this type of medication include sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), mesalamine (Delzicol, Rowasa, others), balsalazide (Colazal) and olsalazine (Dipentum). Which medication you take and how you take it — by mouth or as an enema or suppository — depends on the area of your colon that’s affected.

- Corticosteroids. These medications, which include prednisone and budesonide, are generally reserved for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis that doesn’t respond to other treatments. Corticosteroids suppress the immune system. Due to the side effects, they are not usually given long term.

Immune system suppressors

These medications also reduce inflammation, but they do so by suppressing the immune system response that starts the process of inflammation. For some people, a combination of these medications works better than one medication alone.

Immunosuppressant medications include:

- Azathioprine (Azasan, Imuran) and mercaptopurine (Purinethol, Purixan). These are commonly used immunosuppressants for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. They are often used in combination with medications known as biologics. Taking them requires that you follow up closely with your provider and have your blood checked regularly to look for side effects, including effects on the liver and pancreas.

- Cyclosporine (Gengraf, Neoral, Sandimmune). This medication is typically reserved for people who haven’t responded well to other medications. Cyclosporine has the potential for serious side effects and is not for long-term use.

- “Small molecule” medications. More recently, orally delivered agents, also known as “small molecules,” have become available for IBD treatment. These include tofacitinib (Xeljanz), upadacitinib (Rinvoq) and ozanimod (Zeposia). These medications may be effective when other therapies don’t work. Main side effects include the increased risk of shingles infection and blood clots.

Biologics

This class of therapies targets proteins made by the immune system. Types of biologics used to treat ulcerative colitis include:

- Infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira) and golimumab (Simponi). These medications, called tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, work by neutralizing a protein produced by your immune system. They are for people with severe ulcerative colitis who don’t respond to or can’t tolerate other treatments. TNF inhibitors are also called biologics.

- Vedolizumab (Entyvio). This medication is approved for treatment of ulcerative colitis for people who don’t respond to or can’t tolerate other treatments. It works by blocking inflammatory cells from getting to the site of inflammation.

- Ustekinumab (Stelara). This medication is approved for treatment of ulcerative colitis for people who don’t respond to or can’t tolerate other treatments. It works by blocking a different protein that causes inflammation.

Surgery

Surgery can eliminate ulcerative colitis and involves removing your entire colon and rectum (proctocolectomy).

In most cases, this involves a procedure called ileoanal anastomosis (J-pouch) surgery. This procedure eliminates the need to wear a bag to collect stool. Your surgeon constructs a pouch from the end of your small intestine. The pouch is then attached directly to your anus, allowing you to expel waste in the usual way. This surgery may require 2 to 3 steps to complete.

In some cases a pouch is not possible. Instead, surgeons create a permanent opening in your abdomen (ileal stoma) through which stool is passed for collection in an attached bag.

You will need more-frequent screening for colon cancer because of your increased risk. The recommended schedule will depend on the location of your disease and how long you have had it. People with inflammation of the rectum, also known as proctitis, are not at increased risk of colon cancer.

If your disease involves more than your rectum, you will require a surveillance colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years.

Who gets ulcerative colitis?

Up to 20% of people with UC have a blood relative who has IBD

Get it! It also affects men and women equally!

Learn about Chron’s Disease tomorrow with what it actually is, the symptoms, the symptoms based on the various intensities, with who is more prone to it with in what percentage!

KNOW THE DIFFERENCE!

KNOW THE DIFFERENCE!

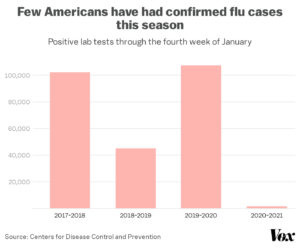

Consider the FLU VACCINE!

Consider the FLU VACCINE!