Part II What is Chron’s Disease actually?

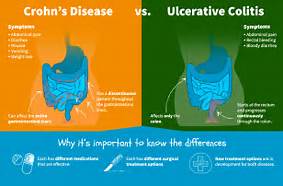

Crohn’s disease

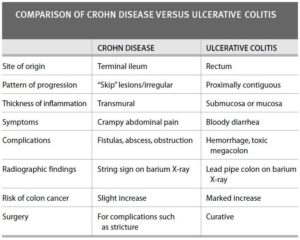

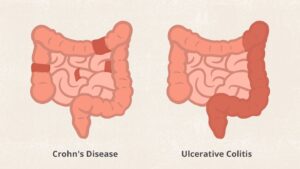

- Inflammation may develop anywhere in the GI tract from the mouth to the anus

- Most commonly occurs at the end of the small intestine

- May appear in patches

- May extend through entire thickness of bowel wall

- About 67% of people in remission will have at least 1 relapse over the next 5 years

(Review in Remember Ulcerative colitis is:

- Limited to the large intestine (colon and rectum)

- Occurs in the rectum and colon, involving a part or the entire colon

- Appears in a continuous pattern

- Inflammation occurs in innermost lining of the intestine

- About 30% of people in remission will experience a relapse in the next year)

Chron’s Disease can cause other parts of the body to become inflamed (due to chronic inflammatory activity) including the joints, eyes, mouth, and skin. In addition, gallstones and kidney stones may also develop as a result of Crohn’s disease.

Moreover, children with the disease may experience decreased growth or delayed sexual development.

Crohn’s Disease is far more common than a lot of people think, and it can be a serious disease with life-threatening complications if it is not properly treated. The best way to treat Crohn’s disease is to speak with your doctor regarding Crohn’s disease symptoms and diagnosis. The more you know about the issue, the more likely you will be to recognize it in your own body.

Crohn’s disease symptoms can include: Frequent and recurring diarrhea with,rectal bleeding,Unexplained weight loss, Fever, Abdominal pain and cramping, Fatigue and a feeling of low energy, & Reduced appetite.

Crohn’s can affect the entire GI tract — from the mouth to the anus — and can be progressive, so over time, your symptoms could get worse. That’s why it’s important that you have an open and honest conversation about your symptoms, since your doctor will use that information to help determine what treatment plan is best for you.

It might be helpful that you understand the differences between mild, moderate and severe symptoms, since your doctor may ask your similar questions in S/S your having to distinguish it you are in mild to very severe symptoms.

Crohn’s Disease Symptom Severity

Mild to Moderate

You may have symptoms such as:

- Frequent diarrhea

- Abdominal pain (but can walk and eat normally)

- No signs of:

- Dehydration

- High fever

- Abdominal tenderness

- Painful mass

- Intestinal obstruction

- Weight loss of more than 10%

Moderate to Severe

You may have symptoms such as:

- Frequent diarrhea

- Abdominal pain or tenderness

- Fever

- Significant weight loss

- Significant anemia (a few of these symptoms may include fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness and headache)

Very Severe

Persistent symptoms despite appropriate treatment for moderate to severe Crohn’s, and you may also experience:

- High fever

- Persistent vomiting

- Evidence of intestinal obstruction (blockage) or abscess (localized infection or collection of pus). A few of these symptoms may include abdominal pain that doesn’t go away or gets worse, swelling of the abdomen, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation.

- More severe weight loss

Once you and your doctor have discussed your symptoms and created a treatment plan, it’s important to follow directions and take your treatment as prescribed. If you ever have any questions or concerns about your treatment, you should contact your doctor before making any changes or adjustments.

Crohn’s disease is unpredictable. Over time, your symptoms may change in severity, or change altogether. You may go through periods of remission—when you have few or no symptoms. Or your symptoms may come on suddenly, without warning.

Complications:

Crohn’s disease may lead to one or more of the following complications:

- Bowel obstruction. Crohn’s disease can affect the entire thickness of the intestinal wall. Over time, parts of the bowel can scar and narrow, which may block the flow of digestive contents, often known as a stricture. You may require surgery to widen the stricture or sometimes to remove the diseased portion of your bowel.

- Ulcers. Chronic inflammation can lead to open sores (ulcers) anywhere in your digestive tract, including your mouth and anus, and in the genital area (perineum).

- Fistulas. Sometimes ulcers can extend completely through the intestinal wall, creating a fistula — an abnormal connection between different body parts. Fistulas can develop between your intestine and your skin, or between your intestine and another organ. Fistulas near or around the anal area (perianal) are the most common kind.When fistulas develop inside the abdomen, it may lead to infections and abscesses, which are collections of pus. These can be life-threatening if not treated. Fistulas may form between loops of bowel, in the bladder or vagina, or through the skin, causing continuous drainage of bowel contents to your skin.

- Anal fissure. This is a small tear in the tissue that lines the anus or in the skin around the anus where infections can occur. It’s often associated with painful bowel movements and may lead to a perianal fistula.

- Malnutrition. Diarrhea, abdominal pain and cramping may make it difficult for you to eat or for your intestine to absorb enough nutrients to keep you nourished. It’s also common to develop anemia due to low iron or vitamin B-12 caused by the disease.

- Colon cancer. Having Crohn’s disease that affects your colon increases your risk of colon cancer. General colon cancer screening guidelines for people without Crohn’s disease call for a colonoscopy at least every 10 years beginning at age 45. In people with Crohn’s disease affecting a large part of the colon, a colonoscopy to screen for colon cancer is recommended about 8 years after disease onset and generally is performed every 1 to 2 years afterward. Ask your doctor whether you need to have this test done sooner and more frequently.

- Skin disorders. Many people with Crohn’s disease may also develop a condition called hidradenitis suppurativa. This skin disorder involves deep nodules, tunnels and abscesses in the armpits, groin, under the breasts, and in the perianal or genital area.

- Other health problems. Crohn’s disease can also cause problems in other parts of the body. Among these problems are low iron (anemia), osteoporosis, arthritis, and gallbladder or liver disease.

- Medication risks. Certain Crohn’s disease drugs that act by blocking functions of the immune system are associated with a small risk of developing cancers such as lymphoma and skin cancers. They also increase the risk of infections.Corticosteroids can be associated with a risk of osteoporosis, bone fractures, cataracts, glaucoma, diabetes and high blood pressure, among other conditions. Work with your doctor to determine risks and benefits of medications.

- Blood clots.

Treatment:

There is currently no cure for Crohn’s disease, and there is no single treatment that works for everyone. One goal of medical treatment is to reduce the inflammation that triggers your signs and symptoms. Another goal is to improve long-term prognosis by limiting complications. In the best cases, this may lead not only to symptom relief but also to long-term remission.

Anti-inflammatory drugs

Anti-inflammatory drugs are often the first step in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. They include:

- Corticosteroids. Corticosteroids such as prednisone and budesonide (Entocort EC) can help reduce inflammation in your body, but they don’t work for everyone with Crohn’s disease.Corticosteroids may be used for short-term (3 to 4 months) symptom improvement and to induce remission. Corticosteroids may also be used in combination with an immune system suppressor to induce the benefit from other medications. They are then eventually tapered off.

- Oral 5-aminosalicylates. These drugs are generally not beneficial in Crohn’s disease. They include sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), which contains sulfa, and mesalamine (Delzicol, Pentasa, others). Oral 5-aminosalicylates were widely used in the past but now are generally considered of very limited benefit.

Immune system suppressors

These drugs also reduce inflammation, but they target your immune system, which produces the substances that cause inflammation. For some people, a combination of these drugs works better than one drug alone.

Immune system suppressors include:

- Azathioprine (Azasan, Imuran) and mercaptopurine (Purinethol, Purixan). These are the most widely used immunosuppressants for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Taking them requires that you follow up closely with your doctor and have your blood checked regularly to look for side effects, such as a lowered resistance to infection and inflammation of the liver. They may also cause nausea and vomiting.

- Methotrexate (Trexall). This drug is sometimes used for people with Crohn’s disease who don’t respond well to other medications. You will need to be followed closely for side effects.

Biologics

This class of therapies targets proteins made by the immune system. Types of biologics used to treat Crohn’s disease include:

- Vedolizumab (Entyvio). This drug works by stopping certain immune cell molecules — integrins — from binding to other cells in your intestinal lining. Vedolizumab is a gut-specific agent and is approved for Crohn’s disease. A similar medication to vedolizumab known as natalizumab was previously used for Crohn’s disease but is no longer used due to side effect concerns, including a fatal brain disease.

- Infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira) and certolizumab pegol (Cimzia). Also known as TNF inhibitors, these drugs work by neutralizing an immune system protein known as tumor necrosis factor (TNF).

- Ustekinumab (Stelara). This was recently approved to treat Crohn’s disease by interfering with the action of an interleukin, which is a protein involved in inflammation.

- Risankizumab (Skyrizi). This medication acts against a molecule known as interleukin-23 and was recently approved for treatment of Crohn’s disease.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics can reduce the amount of drainage from fistulas and abscesses and sometimes heal them in people with Crohn’s disease. Some researchers also think that antibiotics help reduce harmful bacteria that may be causing inflammation in the intestine. Frequently prescribed antibiotics include ciprofloxacin (Cipro) and metronidazole (Flagyl).

Other medications

In addition to controlling inflammation, some medications may help relieve your signs and symptoms. But always talk to your doctor before taking any nonprescription medications. Depending on the severity of your Crohn’s disease, your doctor may recommend one or more of the following:

- Anti-diarrheals. A fiber supplement, such as psyllium powder (Metamucil) or methylcellulose (Citrucel), can help relieve mild to moderate diarrhea by adding bulk to your stool. For more severe diarrhea, loperamide (Imodium A-D) may be effective.These medications could be ineffective or even harmful in some people with strictures or certain infections. Please consult your health care provider before you take these medications.

- Pain relievers. For mild pain, your doctor may recommend acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) — but not other common pain relievers, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve). These drugs are likely to make your symptoms worse and can make your disease worse as well.

- Vitamins and supplements. If you’re not absorbing enough nutrients, your doctor may recommend vitamins and nutritional supplements.

Surgery

If diet and lifestyle changes, drug therapy, or other treatments don’t relieve your signs and symptoms, your doctor may recommend surgery. Nearly half of those with Crohn’s disease will require at least one surgery. However, surgery does not cure Crohn’s disease.

During surgery, your surgeon removes a damaged portion of your digestive tract and then reconnects the healthy sections. Surgery may also be used to close fistulas and drain abscesses.

The benefits of surgery for Crohn’s disease are usually temporary. The disease often recurs, frequently near the reconnected tissue. The best approach is to follow surgery with medication to minimize the risk of recurrence.

KNOW THE DIFFERENCE!

KNOW THE DIFFERENCE!