Archive | August 2015

QUOTE FOR THE WEEKEND:

“TUESDAY, June 25, 2013 (MedPage Today) — A detailed history of patients with arrhythmia or syncope might need to decrease their cola intake or the origin of the honey they consume, two case studies suggest.”

Chris Kaiser, Cardiology Editor, MedPage Today

What is syncope?

Syncope, also known as fainting, is a sudden, temporary loss of consciousness.

THE CAUSES:

Syncope is caused by a temporary decrease in the flow of blood to the brain. A large number of situations or conditions can cause this decrease in blood flow. They can include straining for a prolonged period of time, common mild illnesses like as simple as the cold or flu or sinusitis, standing up too quickly allowing the blood to drop from the brain in decreasing blood supply to that area, emotionally stressed, heart disease, standing rigidly for a long time, arrhythmias (abnormal heart beats = irregular heartbeats), pain, fright, drugs and alcohol.

Certain heart conditions can cause syncope. They include heart attacks, certain arrhythmia (like atrial fibrillation), hypertropic cardiomyopathy (A disease that involves thickening of the heart muscle which is greatest in size on the L side of the heart since that side of the heart has to pump blood to the feet up to the head and back to the right side of the heart; the Rt. side of the heart only pumps blood from the Rt side of the heart to lungs and back to the L side of the heart with oxygenated blood.) Other conditions causing syncope can be disorders of the heart valves, or heart blocks (a problem with the heart’s electrical system blocked due to the conduction system not going completely from the top to the bottom of the heart which can be slight (1st degree heart block to moderate=2 types of 2nd degree heart block to completely being 3rd degree heart block).

DIAGNOSIS:

Like any other condition in determining the cause we have to use diagnostic tools through certain tests to figure out the actual etiology of the syncope or any symptoms you’re experiencing.

The doctor will start with a thorough physical exam and review of your medical history with significant changes from your last physical or visit with the doctor. The doctor may recommend certain diagnostic tests to determine the cause of your fainting episodes. These tests could include: X-rays, use of a Holter monitor (a device that you wear during the day that records the electrical activity over a period of time), or other diagnostic or imaging testing procedures.

Our doctor might recommend a “tilt-table test”. This test involves a special table that tilts upright. Sometimes, medications are given during the test to help with the diagnosis. Your doctor may order a Stress Test where you walk to run on a treadmill with or without IV contrast to determine if this is possible cardiac situation and if it is than the doctor would further order other cardiac testing from Echocardiogram (soundwaves checking the heart) to microsurgery possibly like an angiogram (cardiac cath)=microsurgery if the situation was a blockage in an artery that needed to be declogged than a angioplasty would be performed if you were a candidate for this procedure, which a cardiologist would decide.

PREVENTION OF THIS PROBLEM:

If this was to prevent cardiac conditions from occurring to stop the syncope from occurring live a life with a healthy diet, balancing exercise and rest and if overweight start a program with both diet and exercise involved. To do it right first go to a cardiologist, if obese or overweight, to do it safe and correctly.

Already with some type of cardiac problem than be compliant in what your cardiologist provides you in your individual plan of care in treating this condition to prevent it worsening or causing other problems as well.

TREATMENT:

Treatment depends on the cause of the fainting spells. If the problems are related to medications the doctor may have to change the dosage or the type of medication. Medications are generally not required to treat syncope, but they might be required to treat the cause of syncope.

Most fainting spells are not dangerous. Individuals usually regain consciousness on their own in a few minutes.

QUOTE FOR FRIDAY:

“A Japanese legend says that if you can’t sleep at night it’s because you are awake in someone else’s dream (I must be in many others dreams.).”

Do you have trouble sleeping?

Insomnia is a sleeping disorder that is characterized by difficulty falling and/or staying asleep. People with Insomnia have one or more of the following symptoms:

- Difficulty falling asleep

- Waking up often during the night and having trouble going back to sleep

- Waking up too early in the morning

- Feeling tired upon waking

- There are noted to be 2 types: Primary and Secondary

- Primary insomnia: Primary insomnia means that a person is having sleep problems that are not directly associated with any other health condition or problem.

- Secondary insomnia: Secondary insomnia means that a person is having sleep problems because of something else, such as a health condition (like asthma, depression, arthritis, cancer or heartburn). Other conditions could be pain, medication they are taking or a substance they are using (like alcohol).Acu

- Causes of acute insomnia can include:

- Insomnia also varies in how long it lasts and how often it occurs. It can be short-term (acute insomnia) or can last a long time (chronic insomnia). It can also come and go, with periods of time when a person has no sleep problems. Acute insomnia can last from one night to a few weeks. Insomnia is called chronic when a person has insomnia at least three nights a week for a month or longer. Significant life stress (job loss or change, death of a loved one, divorce, moving)

- Illness

- Emotional or physical discomfort

- Environmental factors like noise, light, or extreme temperatures (hot or cold) that interfere with sleep

- Some medications (for example those used to treat colds, allergies, depression, high blood pressure and asthma) which may interfere with sleep

- Interferences in normal sleep schedule ( jet lag or switching from a day to night shift, for example)

- Causes of chronic insomnia include:

- Depression and/or anxiety

- Chronic stress

- Pain or discomfort at night

- Symptoms of insomnia can include:

- Sleepiness during the day

- General tiredness

- Irritability

- Problems with concentration or memory

- How Insomnia can be diagnosed: If you think you have insomnia, talk to your health care provider or a doctor who majors in Insomnia. An evaluation may include a physical, a medical history, and a sleep history. You may be asked to keep a sleep diary for a week or two, keeping track of your sleep patterns and how you feel during the day. Your health care provider may want to interview your bed partner about the quantity and quality of your sleep. In some cases, you may be referred to a sleep center for special tests.

- Treatment of InsomniaYou should seek help if your insomnia has become a pattern, or if you often feel fatigued or unrefreshed during the day and it interferes with your daily life. Many people have brief periods of difficulty sleeping (for example, a few days after starting a new job), but if insomnia lasts longer or has become a regular occurrence, you should ask for help.If you don’t feel satisfied after your conversation with your primary care physician, ask for a referral to a doctor who specializes in sleep medicine or consult other available resources. It’s important to find a doctor who has the proper knowledge and training to treat your insomnia.

- Non-Medical (Cognitive & Behavioral) Treatments for InsomniaSome of these techniques can be self-taught, while for others it’s better to enlist the help of a therapist or sleep specialist. Stimulus control helps to build an association between the bedroom and sleep by limiting the type of activities allowed in the bedroom. An example of stimulus control is going to bed only when you are sleepy, and getting out of bed if you’ve been awake for 20 minutes or more. This helps to break an unhealthy association between the bedroom and wakefulness. Sleep restriction involves a strict schedule of bedtimes and wake times and limits time in bed to only when a person is sleeping.

- Medical Treatments for InsomniaDetermining which medication may be right for you depends on your insomnia symptoms and many different health factors. This is why it’s important to consult with a doctor before taking a sleep aid.Alternative Medicine

- There are alternative medicines that may help certain people sleep. It’s important to know that these products are not required to pass through the same safety tests as medications, so their side effects and effectiveness are not as well understood.

- Major classes of prescription insomnia medications include benzodiazepine hypnotics, non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, and melatonin receptor agonists.

- There are many different types of sleep aids for insomnia, including over-the-counter (non-prescription) and prescription medications.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) includes behavioral changes (such as keeping a regular bedtime and wake up time, getting out of bed after being awake for 20 minutes or so, and eliminating afternoon naps) but it adds a cognitive or “thinking” component. CBT works to challenge unhealthy beliefs and fears around sleep and teach rational, positive thinking. There is a good amount of research supporting the use of CBT for insomnia. For example, in one study, patients with insomnia attended one CBT session via the internet per week for 6 weeks. After the treatment, these people had improved sleep quality.

- Relaxation training, or progressive muscle relaxation, teaches the person to systematically tense and relax muscles in different areas of the body. This helps to calm the body and induce sleep. Other relaxation techniques that help many people sleep involve breathing exercises, mindfulness, meditation techniques, and guided imagery. Many people listen to audio recordings to guide them in learning these techniques. They can work to help you fall asleep and also return to sleep in the middle of the night.

- There are psychological and behavioral techniques that can be helpful for treating insomnia. Relaxation training, stimulus control, sleep restriction, and cognitive behavioral therapy are some examples.

- Many cities also have sleep centers and clinics (sometimes connected to a hospital) that offer assessments, testing, and treatment. An Internet search will help you locate the nearest center.

- Start by calling your primary care physician or bringing up the topic of sleep at your next well visit if you have one scheduled. If your doctor is knowledgeable about sleep disorders, he or she will guide you through the next steps, which may involve an assessment and further testing, or a referral to a sleep specialist. Your doctor may also start by giving you some basic information and resources about healthy sleep habits—these behavioral tips may help certain people with insomnia—or discussing potential medical treatment options to consider. Your doctor could refer you to a psychotherapist if your sleep struggles seem connected to anxiety, depression, or a major life adjustment.

QUOTE FOR THURSDAY:

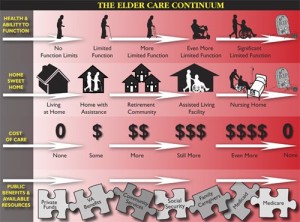

OPTIONS IN IN CARING FOR A PARENT WHEN IT IS UNMANAGABLE FOR YOU ALONE TO CARE FOR MOM OR DAD.

Deciding to move out of one’s home and into a different type of housing is often a difficult decision for elders or people with disabilities and their caregivers. Caregivers often struggle to care for loved ones so they are able to remain at home as long as possible. However, there often comes a time when moving someone to a residential care facility may become the most realistic way to provide the best care, and the only way to relieve a caregiver’s overwhelming burden.

If you or a loved one is considering a move to an out-of-home living situation, you might be confused by all the housing options. Will a board-and-care home, assisted living facility, or nursing home be the best choice? And what are the differences between these housing options?

This Fact Sheet provides an overview of residential options that offer some level of medical and/or personal care services for elders and others who need assistance in daily living. It does not cover housing options such as independent living and senior apartments, which do not include health services.

The Fact Sheet describes different types of housing, how much they cost, and how to choose a good facility. The goal is to help you decide which facility would be the most comfortable, safe, appropriate and affordable for your loved one.

Is It Time for a Move?

An increase in certain “special care needs” often triggers discussions about moving into residential care. These care needs might include: incontinence, wandering, sleeplessness, combative and other difficult dementia behavior, tube feeding, skin care treatment, and assistance with transferring (e.g., moving someone from bed to chair). It is common to find that the emotional well-being of the care receiver is also a factor: if the care receiver is suffering from depression, for example, it is more difficult for the caregiver to sustain long-term care.

Another turning point is when the person can no longer attend adult day care, requiring the family to provide care 24 hours a day. It is also common for a placement decision to be made after a crisis or hospitalization. A decline in the physical health of the caregiver is another major reason for placement.

Making the Transition from Home to Residential Facility

If you and your family have decided that it may be time for your loved one to move into a facility, the following tips may help towards a peaceful transition:

- Don’t wait for a crisis: plan ahead. Learning about your options can help reduce the confusion and trauma of a move and lessen the emotional ordeal for both you and your loved one. A thoughtful comparison of available choices will help all involved gain insight into finding the most appropriate setting and level of care for your loved one. The process will assist you in making informed decisions that will help you and your family regain a sense of control over what might feel like an unmanageable situation.

- Have a family meeting: Whenever possible, the decision to move into a facility should be discussed fully with your loved one. (When you are dealing with a cognitive disorder such as advanced Alzheimer’s disease, however, you may have to make the decisions without their participation.) In addition, you and your family members, a social worker, case manager, hospital discharge planner, financial planner and/or spiritual advisor can be helpful in making sure that your loved one’s needs will be met and that your family feels comfortable with the move.

- Determine your loved one’s particular housing needs: One of the most important steps in finding the right facility for your loved one is thinking about his or her particular needs.

- What level of care does she or he need?

- How much independence and privacy is the right level for your loved one?

- Does your loved one have any physical or cognitive impairment?

- What are your loved one’s likely future needs?

- Is a smaller or larger facility likely to work better?

- Get support for you: Many caregivers feel guilty about moving a loved one into a facility. If you are having these feelings, it may help to speak to a counselor or support group. And remember that putting your loved one in a residential facility may be the best choice for his or her health and safety as well as your own well-being.

Getting Started

One place to begin your search for elder housing (and caregiver support programs for you) is with your local Area Agency on Aging (AAA). You can find your local AAA by visiting the Eldercare Locator website or by calling (800) 677-1116.

- Your AAA can provide the following:

- A list of licensed facilities in your area.

- Licensing regulations for your state.

- Contact information for your long-term care ombudsman.

- Contact information for Medicare and Medicaid in your state (Medi-Cal in California).

One helpful way to begin this process is to hire a geriatric care manager familiar with local facilities to help you find a new residence for your loved one. Care managers usually charge a fee for their services. To find a geriatric care manager near you, visit the National Association of Professional Geriatric Care Managers or call (520) 881-8008. Some community organizations may also provide this service at lower cost.

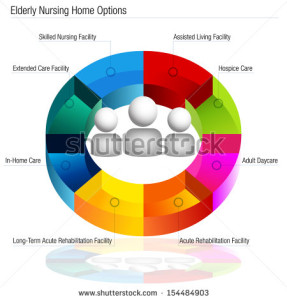

Types of Facilities: What’s in a Name?

To help you determine which type of housing might be right for your loved one, you must become familiar with what options exist and what services they provide. Housing options vary widely in terms of size, cost, services and facilities. Be aware also that the terms used to describe these options may vary from state to state. The following list describes the most common housing options and key features (please note that key features listed are normally, but not always, present).

Board and Care Homes

(Also known as: Residential Care for the Elderly [RCFE], Personal Care Homes, Sheltered Housing, Homes for Adults, Domiciliary Care, Adult Foster Care or Senior Group Homes.)

Board and care homes are smaller in scale than assisted living facilities, though many states consider them to be one form of assisted living. Some board and care facilities are specialized (e.g., serving only residents with Alzheimer’s disease). They provide a room, meals, and help with daily activities.

- Number of Residents: Usually up to six.

- Cost: Often lower than other facilities.

- Setting: Many of these are in traditional homes in residential neighborhoods. Residents may share bathrooms, bedrooms and living spaces.

- Services: Meals; help with daily activities (though some provide limited nursing level care, such as administering medications); and sometimes social activities.

- Medicare/Medicaid Reimbursable: Medicare does not cover; Medicaid 1915c waivers can be used in most states to pay for services. SSI may also be used for payments.

- Features: Personal, family-style care.

For more information:

Contact the Area Agency on Aging near you (see Getting Started) or visit their online Helpguide.

Assisted Living Facilities

(Also known as Residential Care Facilities or Adult Congregate Living.)

Assisted living communities are designed for individuals who have difficulty living alone, but do not need daily nursing care. Unfortunately, the definition of the term “assisted living” varies from state to state, as each state has its own licensing requirements and regulations. Families need to visit facilities and ask detailed questions to know what services each facility offers.

- Number of Residents: Varies widely; 40 to 100 rooms is typical.

- Cost: Midlevel; the national average in 2004 was $2,524 per month, but may be much higher in some communities. Costs depend on what level of service the person requires, and increase as the number of services increases. Most facilities charge a basic monthly rate that covers rent and utilities, and then charge separately for services. Many facilities also charge a one-time entrance fee.

- Setting: Facilities may only have bedrooms or they may have full apartments, with a large dining room and lounge for residents to come together.

- Services: Housekeeping services (as in a hotel); meals; help with daily activities; transportation to appointments; medication reminders and administration; social and recreational activities; 24-hour supervision.

- Medicare/Medicaid Reimbursable: Medicare does not cover; Medicaid 1915c waivers can be used in most states to pay for services.

- Features: Apartment-style living; privacy and independence with a menu of services to choose from.

For more information:

Choosing An Assisted Living Residence: A Consumer’s Guide

National Center for Assisted Living (NCAL) (202) 842-4444 http://www.ahcancal.org/ncal/Pages/index.aspx

Assisted Living Federation of America (703) 894-1805 http://www.alfa.org

Provider Magazine’s 2012 Top 40 Assisted Living Chains http://www.providermagazine.com/reports/pages/0612/2012-top-40-assisted-living-companies.aspx

Consumer Consortium on Assisted Living (703) 533-8121 http://www.ccal.org

Nursing Homes

(Also called Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF), Convalescent Hospitals or Rest Home).

Nursing homes provide care for individuals who need nursing care without being in a hospital, as well as recreation and help with daily activities.

- Number of Residents: Average of 109 beds per nursing home nationally.

- Cost: High. The national average in 2004 was $5,070-5,760 per month; costs vary widely among geographic regions.

- Setting: Large facilities, often in a hospital- like setting.

- Services: Medical services and 24-hour nursing care; help with daily activities; recreation; rehabilitative care (e.g., physical therapy).

- Medicare/Medicaid Reimbursable: Medicare pays for up to 100 days of care, however, individuals must be referred by a physician upon hospital discharge and have the need for skilled nursing care. Often, Medicare will pay only for a few weeks of rehabilitation services after hospitalization. Medicaid is accepted by many homes for ongoing care, but a person’s eligibility must be established.

- Features: Provides the highest level of supervision and medical services for residents compared to other facilities. A more recent movement, spearheaded by such organizations as the Eden Alternative and Greenhouse Project, aims to provide more client-centered care than traditional nursing home models. However, these alternatives are not yet available in all areas of the country.

For more information:

National Citizens Coalition for Nursing Home Reform (202) 332-2275 http://www.nccnhr.org

Nursing Home Compare (800) MEDICARE http://www.medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare/search.html

For nationwide nursing home ratings and quality of care information: http://www.Memberofthefamily.net

National Long Term Care Ombudsman Resource Center (202)332-2275 http://www.ltcombudsman.org

Eden Alternative/Green House Project http://www.edenalt.com/

Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs)

(Also known as Life Care Facilities.)

CCRCs are usually large complexes that offer options ranging from independent living to skilled nursing home care. These facilities are specifically designed to provide lifetime care within one community, so residents often move there when still independent and then change residences within the community if medical and/or personal care services are needed. Residents cannot be made to leave because of a worsening condition.

- Number of Residents: Many.

- Cost: High. Most communities require a buy-in fee and monthly payments. These fees can range from lows of $20,000 to highs of $400,000 and more. Monthly payments can range from $200 to $2,500 or more.

- Setting: Large campuses with many buildings, usually including separate homes, assisted living facilities and nursing homes.

- Services: Depend on which type of facility person resides in. All levels of care are accommodated.

- Medicare/Medicaid Reimbursable: Medicare does not cover; Medicaid may pay for services in nursing home.

- Features: Ability to move to higher level of care if needed without having to relocate to a different community.

For more information:

Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) (866) 888-1122 CARF-CCAC offers an online search of accredited continuing care retirement communities. To request a printed list of accredited providers in your region call the number listed above.

QUOTE FOR WEDNESDAY:

Things not to say to your elderly parent for the best of both party’s.

“Seniors often know that their memory and cognitive and physical abilities are declining, and reminders are only hurtful,” says Francine Lederer, a psychotherapist in Los Angeles who works with “sandwich generation” patients and their parents. But even when we manage to hold our tongue, frustration lingers. That’s when we have to be doubly mindful, because by repressing those emotions, we’re more likely to have an emotional outburst. “You might be justifiably annoyed,” Lederer says, “but take a step back and consider how your parent must feel as she faces her diminished capacities.” When people first start “slipping,” they are aware of the loss, and they are often terrified, scared and saddened. Since forewarned is forearmed, here are eight common things we often catch ourselves saying plus suggestions for less hurtful ways to say them.

1. “How can you not remember that!?” That lengthy discussion you had last week with your dad about getting the car inspected might as well never have happened. Seniors often lose short-term memory before long-term and forget all kinds of things we think are monumentally important, like where they put their glasses or the keys — or when to take the car in to the shop. Say instead: “See this sticker? If the car isn’t inspected before the end of the month, a cop will give you a very expensive reminder.” Place a few Post-its notes around — on the dashboard, fridge and bathroom mirror. Add a smiley face to keep the tone light. And if you still think your parent might forget, make the appointment then call your mom that morning to remind her.

2. “You could do that if you really tried.” How hard is it to change the light bulb in the table lamp? Well, if your hands shake a lot or you can’t reach the shelf where you keep spare bulbs — or you’ve grown wary of electrical outlets — very hard. Simple tasks, like tying shoes, can become next-to-impossible if you have arthritis in your fingers or your back doesn’t bend easily. And being shamed into trying something doesn’t help. Say instead: “Let me watch and see where you’re having trouble so we can figure out how this can get done.” Or if you live out of town: “Ask (So-and-so) for help.” Seniors, like everyone else, want to maintain their independence. But if a project is truly beyond their capabilities and they either don’t know anyone who could help (or won’t ask), you might want to try to find someone who can lend a hand. (MORE: Is How to Be a Loving Advocate for Your Parents)

3. “I just showed you how to use the DVR yesterday.” Learning new technology is tough for any adult, but gadgets with lots of buttons and options pose a special challenge for someone whose cognition or eyesight is failing. Even those of us with nimble fingers and well-functioning frontal lobes can be stymied by a new device that labels the controls differently from the one we are used to. Say instead: “The blue button on top turns the TV on, and there’s one set of arrows for changing the channel and another for the volume. I’ll show you again.” Better yet — ask your parents’ cable or satellite provider to recommend a senior-friendly remote control with a simple design. Some companies give these to seniors for a nominal charge. If not, purchase one at a local electronics store. Or if they’re okay following instructions, you could write or print out step-by-step directions in large, legible type and leave it near the remote or listings guide. (MORE: Technology Buying Guide for First-Time Users)

4. “What does that have to do with what we’re talking about?” One minute you and your dad are discussing summer vegetables and the next he’s talking about a problem with the sprinkler system. What happened? Conversations with elderly parents often “go rogue” — either because they can’t keep their mind on the thread or they are simply bored and want to change the subject. Say instead: “I was telling you about my garden. You love my fresh lettuce!” If the subject is important to you, try to bring the conversation back on track without pointing a finger at the senior’s slipping powers of conversation. And to avoid suppressing genuine anger or sadness, gently explain why the conversation was important to you. Another option: Say nothing and just listen.

5. “You already told me that.” And you don’t ever repeat yourself? We all say things more than once — but because elderly parents seem to do it all the time, we lose our patience with them. Say instead: “No kidding?! And don’t tell me that the next thing you did was . . . .” Yes, you can make a joke out of it — but only if your parent won’t feel hurt. Best-case scenario: Your mom or dad will feel amused and relaxed enough to join in.

6. “I want your silver tea service when you die.” This is wrong on so many levels. Even worse than casually referencing their death is the fact that you come off like a circling vulture. Say instead: “I have been reading how it’s helpful for everyone if parents leave a list specifying what will be left to whom.” Stress that unless they make their wishes known, there may be conflict among siblings and other relatives. I know one woman who gave her children and grandchildren stickers which they could use to mark items they desired (by placing them in the back or on the bottom).

7. “Wake up! (Or shhhh!) I thought you wanted to see this.” The darkened halls of concerts, movies, plays and religious services (or even the TV room at home) cue our elderly parents that it’s time for a quick snooze — which might be OK if there aren’t people around you trying to hear the show. There’s no need to remind older people that they’re committing a faux pas. And if their hearing is diminished, they may not realize that everyone can hear them “whisper.” Say instead: “Mom, I know you don’t want to miss this.” Most likely she’ll fall asleep again. Then it’s up to you how many times you want to bother with the nudges — and not take it personally that your parent fell asleep on you.

8. “Hel-lo?! Your grandson’s name is Ryan.” How many times have you called your husband by the dog’s name? Mixing up appellations can be a sign of cognitive impairment — or just a normal problem with word recall. The more it happens, though, the more likely it is that your parent is moving into a stage where he needs medical intervention. Say instead: “It’s Ryan, Dad. Your first grandson’s name is Ryan.” There aren’t a lot of different ways to say this: The difference here is how you say it. Don’t sound critical or angry; say it gently and with a friendly smile. If your father is truly confused, he’ll probably be relieved that you’re not offended. If it’s just a slip of the tongue, he’ll be glad you’re not annoyed. If he really truly can’t remember your children’s names, you have larger issues to deal with. The most important thing, Lederer stresses, is that as our parents age, we go out of our way to maintain good relationships. “When dealing with elderly people, let your motto be, ‘Reframe, don’t blame,’” she says. A slip of the tongue can unleash a world of hurt and ill will. As exasperating as elderly parents can be, spouting off without thinking will only make them — and you — feel bad.

QUOTE FOR TUESDAY

Lillian Carter (August 15, 1898 – October 30, 1983) was the mother of former President of the United States, Jimmy Carter.