Suicide is a major public health problem and a leading cause of death in the United States. The effects of suicide go beyond the person who acts to take his or her life: it can have a lasting effect on family, friends, and communities. This fact sheet, developed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), can help you, a friend, or a family member learn about the signs and symptoms, risk factors and warning signs, and ongoing research about suicide and suicide prevention.

What Is Suicide?

Suicide is when people direct violence at themselves with the intent to end their lives, and they die because of their actions. It’s best to avoid the use of terms like “committing suicide” or a “successful suicide” when referring to a death by suicide as these terms often carry negative connotations.

A suicide attempt is when people harm themselves with the intent to end their lives, but they do not die because of their actions.

Who Is at Risk for Suicide?

Suicide does not discriminate. People of all genders, ages, and ethnicities can be at risk.

The main risk factors for suicide are:

- A prior suicide attempt

- Depression and other mental health disorders

- Substance abuse disorder

- Family history of a mental health or substance abuse disorder

- Family history of suicide

- Family violence, including physical or sexual abuse

- Having guns or other firearms in the home

- Being in prison or jail

- Being exposed to others’ suicidal behavior, such as a family member, peer, or media figure

- Medical illness

- Being between the ages of 15 and 24 years or over age 60

Even among people who have risk factors for suicide, most do not attempt suicide. It remains difficult to predict who will act on suicidal thoughts.

Are certain groups of people at higher risk than others?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), men are more likely to die by suicide than women, but women are more likely to attempt suicide. Men are more likely to use more lethal methods, such as firearms or suffocation. Women are more likely than men to attempt suicide by poisoning.

Also per the CDC, certain demographic subgroups are at higher risk. For example, American Indian and Alaska Native youth and middle-aged persons have the highest rate of suicide, followed by non-Hispanic White middle-aged and older adult males. African Americans have the lowest suicide rate, while Hispanics have the second lowest rate. The exception to this is younger children. African American children under the age of 12 have a higher rate of suicide than White children. While younger preteens and teens have a lower rate of suicide than older adolescents, there has been a significant rise in the suicide rate among youth ages 10 to 14. Suicide ranks as the second leading cause of death for this age group, accounting for 425 deaths per year and surpassing the death rate for traffic accidents, which is the most common cause of death for young people.

Why do some people become suicidal while others with similar risk factors do not?

Most people who have the risk factors for suicide will not kill themselves. However, the risk for suicidal behavior is complex. Research suggests that people who attempt suicide may react to events, think, and make decisions differently than those who do not attempt suicide. These differences happen more often if a person also has a disorder such as depression, substance abuse, anxiety, borderline personality disorder, and psychosis. Risk factors are important to keep in mind; however, someone who has warning signs of suicide may be in more danger and require immediate attention.

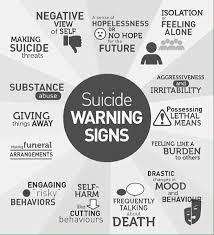

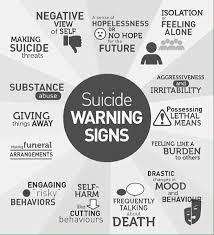

What Are the Warning Signs of Suicide?

The behaviors listed below may be signs that someone is thinking about suicide.

- Talking about wanting to die or wanting to kill themselves

- Talking about feeling empty, hopeless, or having no reason to live

- Planning or looking for a way to kill themselves, such as searching online, stockpiling pills, or newly acquiring potentially lethal items (e.g., firearms, ropes)

- Talking about great guilt or shame

- Talking about feeling trapped or feeling that there are no solutions

- Feeling unbearable pain, both physical or emotional

- Talking about being a burden to others

- Using alcohol or drugs more often

- Acting anxious or agitated

- Withdrawing from family and friends

- Changing eating and/or sleeping habits

- Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge

- Taking risks that could lead to death, such as reckless driving

- Talking or thinking about death often

- Displaying extreme mood swings, suddenly changing from very sad to very calm or happy

- Giving away important possessions

- Saying goodbye to friends and family

- Putting affairs in order, making a will

Do People Threaten Suicide to Get Attention?

Suicidal thoughts or actions are a sign of extreme distress and an alert that someone needs help. Any warning sign or symptom of suicide should not be ignored. All talk of suicide should be taken seriously and requires attention. Threatening to die by suicide is not a normal response to stress and should not be taken lightly.

If You Ask Someone About Suicide, Does It Put the Idea Into Their Head?

Asking someone about suicide is not harmful. There is a common myth that asking someone about suicide can put the idea into their head. This is not true. Several studies examining this concern have demonstrated that asking people about suicidal thoughts and behavior does not induce or increase such thoughts and experiences. In fact, asking someone directly, “Are you thinking of killing yourself,” can be the best way to identify someone at risk for suicide.

What Should I Do if I Am in Crisis or Someone I Know Is Considering Suicide?

If you or someone you know has warning signs or symptoms of suicide, particularly if there is a change in the behavior or a new behavior, get help as soon as possible.

Often, family and friends are the first to recognize the warning signs of suicide and can take the first step toward helping an at-risk individual find treatment with someone who specializes in diagnosing and treating mental health conditions. If someone is telling you that they are going to kill themselves, do not leave them alone. Do not promise anyone that you will keep their suicidal thoughts a secret. Make sure to tell a trusted friend or family member, or if you are a student, an adult with whom you feel comfortable. You can also contact the resources noted below.

Leading Cause of Death in the United States (2016)

Data Courtesy of CDC

|

Select Age Groups |

| Rank |

10-14 |

15-24 |

25-34 |

35-44 |

45-54 |

55-64 |

All Ages |

| 1 |

Unintentional

Injury

847 |

Unintentional

Injury

13,895 |

Unintentional

Injury

23,984 |

Unintentional

Injury

20,975 |

Malignant

Neoplasms

41,291 |

Malignant

Neoplasms

116,364 |

Heart

Disease

635,260 |

| 2 |

Suicide

436 |

Suicide

5,723 |

Suicide

7,366 |

Malignant

Neoplasms

10,903 |

Heart

Disease

34,027 |

Heart

Disease

78,610 |

Malignant

Neoplasms

598,038 |

| 3 |

Malignant

Neoplasms

431 |

Homicide

5,172 |

Homicide

5,376 |

Heart

Disease

10,477 |

Unintentional

Injury

23,377 |

Unintentional

Injury

21,860 |

Unintentional

Injury

161,374 |

| 4 |

Homicide

147 |

Malignant

Neoplasms

1,431 |

Malignant

Neoplasms

3,791 |

Suicide

7,030 |

Suicide

8,437 |

CLRD

17,810 |