We are in winter now with the sports this season that can be very dangerous. Football with hockey and boxing already started and yet they maybe very exciting they unfortunately can still can be severely dangerous. One of the reasons when a football quaterback catches after hiked the ball or in a kick off to the other team the player who catches the ball and not running it out starts no longer at the 20 but the 25 yard line, is done all for more safety even though some of us football fanatics think how wimpy.

The NFL now even takes action. Through Fall and Winter Sports TBI Awareness Month, The Johnny OTM Foundation (Johnny O) is hoping to raise awareness regarding the health risks athletes face when they participate in winter sports, specifically traumatic brain injuries and concussions. September is a great time to put a spotlight on fall/winter sports safety and preventive measures athlete can take to avoid TBIs and concussions.

The mission of Johnny O “is to educate the American public to the growing seriousness of Alzheimer’s, Dementia and Traumatic Brain Injuries in the American population by raising the necessary donations through strategic research initiatives and heightened public awareness to accomplish our objectives.”1 Fall and Winter Sports TBI Awareness Month is one of many initiatives Johnny O is undertaking to not only raise public awareness, but also improve safety and reduce TBIs in Americans of all ages.

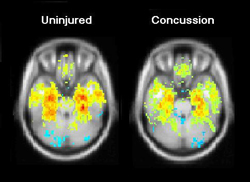

A concussion is a traumatic brain injury that alters the way your brain functions. Effects are usually temporary but can include headaches and problems with concentration, memory, balance and coordination.

Although concussions usually are caused by a blow to the head, they can also occur when the head and upper body are violently shaken. These injuries can cause a loss of consciousness, but most concussions do not. Because of this, some people have concussions and don’t realize it.

Concussions are common, particularly if you play a contact sport, such as football. But every concussion injures your brain to some extent. This injury needs time and rest to heal properly. Most concussive traumatic brain injuries are mild, and people usually recover fully.

Remember the key to a brain concussion fully recovering is not to have impact to the head happening over and over again. Based on the same concept if you get hit in the same spot over and over again anywhere in the body bruising to actual injury will happen whether it be muscle or bone. Well get hit in the head over and over again like in sports especially boxing but now the big conversation with football even with a helmet on you will cause a permanent damage to the brain. A perfect example of this is a boxer that gets hit over an over again to the head in a boxing ring. The head is just another area of the body and no different than other areas of our body.

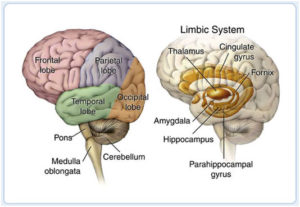

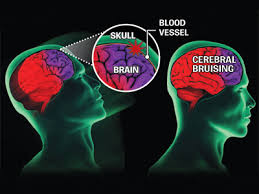

What actually happens is the concussion is most often caused by a sudden direct blow or bump to the head. The brain is made of soft tissue. It’s cushioned by spinal fluid and encased in the protective shell of the skull. When you sustain a concussion, the impact can jolt your brain. Sometimes, it literally causes it to move around in your head. Traumatic brain injuries can cause bruising, damage to the blood vessels, and injury to the nerves.

The result? Your brain doesn’t function normally. If you’ve suffered a concussion, vision may be disturbed, you may lose equilibrium, or you may fall unconscious. In short, the brain is confused. That’s why Bugs Bunny often saw stars after getting whacked in the head in his cartoon by some other character.

The new uptake with football is being concerned with players getting concussions from getting hit by their opponent players whether it be defense or offense while playing the game. Concussions have become big business in the football world. With 1,700 players in the NFL, 66,000 in the college game, 1.1 million in high school and 250,000 more in Pop Warner, athletes and families across the country are eager to find ways to cut the risks of brain injury, whose terrifying consequences regularly tear across the sports pages. And a wave of companies offering diagnostic tools and concussion treatments are just as eager to sell them peace of mind.

That’s actually a slogan for one company. ImPACT, the maker of the world’s most popular concussion evaluation system, offers a 20-minute computerized test that players can take via software or online to measure verbal and visual memory, processing speed, reaction time and impulse control. The idea behind ImPACT (Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing) and similar batteries is that doctors or athletic trainers can give a baseline test to a healthy athlete, conduct follow-up tests after an injury and then compare the results to help figure out when it’s OK to return the athlete to play. Selling itself as “Valid. Reliable. Safe,” ImPACT dominates the testing market and has spread throughout the sports world: Most NFL clubs use the test, as do all MLB, MLS and NHL clubs, the national associations for boxing, hockey and soccer in the U.S., and nine auto racing circuits.

A total of 87 out of 91 former NFL players have tested positive for the brain disease at the center of the debate over concussions in football, according to new figures from the nation’s largest brain bank focused on the study of traumatic head injury.

Researchers with the Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University have now identified the degenerative disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, in 96 percent of NFL players that they’ve examined and in 79 percent of all football players. The disease is widely believed to stem from repetitive trauma to the head, and can lead to conditions such as memory loss, depression and dementia.

In total, the lab has found CTE in the brain tissue in 131 out of 165 individuals who, before their deaths, played football either professionally, semi-professionally, in college or in high school.

Forty percent of those who tested positive were the offensive and defensive linemen who come into contact with one another on every play of a game, according to numbers shared by the brain bank with FRONTLINE. That finding supports past research suggesting that it’s the repeat, more minor head trauma that occurs regularly in football that may pose the greatest risk to players, as opposed to just the sometimes violent collisions that cause concussions.

But the figures come with several important caveats, as testing for the disease can be an imperfect process. Brain scans have been used to identify signs of CTE in living players, but the disease can only be definitively identified posthumously. As such, many of the players who have donated their brains for testing suspected that they had the disease while still alive, leaving researchers with a skewed population to work with.

Even with those caveats, the latest numbers are “remarkably consistent” with past research from the center suggesting a link between football and long-term brain disease, said Dr. Ann McKee, the facility’s director and chief of neuropathology at the VA Boston Healthcare System.

“People think that we’re blowing this out of proportion, that this is a very rare disease and that we’re sensationalizing it,” said McKee, who runs the lab as part of a collaboration between the VA and BU. “My response is that where I sit, this is a very real disease. We have had no problem identifying it in hundreds of players.”

In a statement, a spokesman for the NFL said, “We are dedicated to making football safer and continue to take steps to protect players, including rule changes, advanced sideline technology, and expanded medical resources. We continue to make significant investments in independent research through our gifts to Boston University, the [National Institutes of Health] and other efforts to accelerate the science and understanding of these issues.”

The latest update from the brain bank, which in 2010 received a $1 million research grant from the NFL, comes at a time when the league is able to boast measurable progress in reducing head injuries. In its 2015 Health & Safety Report, the NFL said that concussions in regular season games fell 35 percent over the past two seasons, from 173 in 2012 to 112 last season. A separate analysis by FRONTLINE that factors in concussions reported by teams during the preseason and the playoffs shows a smaller decrease of 28 percent.