What is this condition?

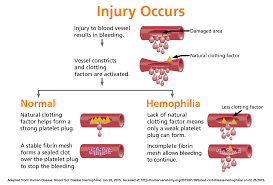

Hemophilia is a bleeding disorder characterized by low levels of clotting factor proteins. Correct diagnosis of Hemophilia is essential to providing effective treatment. Blood Center of Wisconsin offers one of the largest diagnostic menus to accurately and confidently diagnose Hemophilia.

The X and Y chromosomes are called sex chromosomes. The gene for hemophilia is carried on the X chromosome. Hemophilia is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner. Females inherit two X chromosomes, one from their mother and one from their father (XX). Males inherit an X chromosome from their mother and a Y chromosome from their father (XY). That means if a son inherits an X chromosome carrying hemophilia from his mother, he will have hemophilia. It also means that fathers cannot pass hemophilia on to their sons.

But because daughters have two X chromosomes, even if they inherit the hemophilia gene from their mother, most likely they will inherit a healthy X chromosome from their father and not have hemophilia. A daughter who inherits an X chromosome that contains the gene for hemophilia is called a carrier. She can pass the gene on to her children. Hemophilia can occur in daughters, but is rare.

For a female carrier, there are four possible outcomes for each pregnancy:

- A girl who is not a carrier

- A girl who is a carrier

- A boy without hemophilia

- A boy with hemophilia

Hemophilia is an X-linked inherited bleeding disorder caused by mutation of the F8 gene that encodes for coagulation factor VIII or the F9 gene that encodes for coagulation factor IX. The degree of plasma factor deficiency correlates with both the clinical severity of disease and genetic findings. Severe hemophilia is characterized by plasma factor VIII or factor IX levels of under 1 IU/dl. Moderate and mild hemophilia are characterized by factor VIII or factor IX levels of 1-5 IU/dL or 6 – 40 IU/dL, respectively. Genetic analysis is useful for identification of the underlying genetic defect in males with severe, moderate or mild hemophilia and for determination of carrier status in the female individuals within their families. Additionally, data is emerging regarding the correlation between a patients mutation status and the risk of that patient developing an inhibitor.

People with hemophilia A often, bleed longer than other people. Bleeds can occur internally, into joints and muscles, or externally, from minor cuts, dental procedures or trauma. How frequently a person bleeds and the severity of those bleeds depends on how much FVIII is in the plasma, the straw-colored fluid portion of blood.

Normal plasma levels of FVIII range from 50% to 150%. Levels below 50%, or half of what is needed to form a clot, determine a person’s symptoms.

Mild hemophilia A- 6% up to 49% of FVIII in the blood. People with mild hemophilia Agenerally experience bleeding only after serious injury, trauma or surgery. In many cases, mild hemophilia is not diagnosed until an injury, surgery or tooth extraction results in prolonged bleeding. The first episode may not occur until adulthood. Women with mild hemophilia often experience menorrhagia, heavy menstrual periods, and can hemorrhage after childbirth.

Moderate hemophilia A. 1% up to 5% of FVIII in the blood. People with moderate hemophilia A tend to have bleeding episodes after injuries. Bleeds that occur without obvious cause are called spontaneous bleeding episodes.

Severe hemophilia A. <1% of FVIII in the blood. People with severe hemophilia A experience bleeding following an injury and may have frequent spontaneous bleeding episodes, often into their joints and musclesHemophilia A and B are diagnosed by measuring factor clotting activity. Individuals who have hemophilia A have low factor VIII clotting activity. Individuals who have hemophilia B have low factor IX clotting activity.Genetic testing is usually used to identify women who are carriers of a FVIII or FIX gene mutation, and to diagnose hemophilia in a fetus during a pregnancy (prenatal diagnosis). It is sometimes used to diagnose individuals who have mild symptoms of hemophilia A or B.

For Diagnosing the condition:

Genetic testing is also available for the factor VIII gene and the factor IX gene. Genetic testing of the FVIII gene finds a disease-causing mutation in up to 98 percent of individuals who have hemophilia A. Genetic testing of the FIX gene finds disease-causing mutations in more than 99 percent of individuals who have hemophilia B.

For Treating the condition:

There is currently no cure for hemophilia. Treatment depends on the severity of hemophilia.People who have moderate to severe hemophilia A or B may need to have an infusion of clotting factor taken from donated human blood or from genetically engineered products called recombinant clotting factors to stop the bleeding. If the potential for bleeding is serious, a doctor may give infusions of clotting factor to avoid bleeding (preventive infusions) before the bleeding begins. Repeated infusions may be necessary if the internal bleeding is serious. When a person who has hemophilia has a small cut or scrape, using pressure and a bandage will take care of the wound. An ice pack can be used when there are small areas of bleeding under the skin.

When bleeding has damaged joints, physical therapy is used to help them function better. Physical therapy helps to keep the joints moving and prevents the joints from becoming frozen or badly deformed. Sometimes the bleeding into joints damages them or destroys them. In this situation, the individual may be given an artificial joint.

Treatment may involve slow injection of a medicine called desmopressin (DDAVP) by the doctor into one of the veins. DDAVP helps to release more clotting factor to stop the bleeding. Sometimes, DDAVP is given as a medication that can be breathed in through the nose (nasal spray).

Researchers have been working to develop a gene replacement treatment (gene therapy) for Hemophilia A. Research of gene therapy for hemophilia A is now taking place. The results are encouraging. Researchers continue to evaluate the long-term safety of gene therapies. The hope is that there will be a genetic cure for hemophilia in the future.