Long-Term Care Facilities

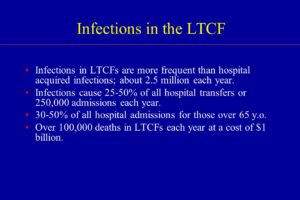

Long-term care facilities (LTCFs), including rehabilitation centers, psychiatric hospitals, and residences for the disabled, differ from acute care hospitals in many ways. They are essentially a home for their residents, but many residents are often transferred between the LTCF and acute treatment hospitals as health needs arise. Because of their nature, LTCFs pose some unique risks for HAIs.

Nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities for the care of the elderly are the most common type of LTCF. In the United States, about 1.5 million people reside in 16,100 nursing homes. It is estimated that 765,000 to 2.8 million of these residents suffer from infections each year. Risk factors for infection are specific in this vulnerable population and include advanced age, incontinence, immobility, lower immunity, dysphagia, age-related skin changes, frequent hospitalizations, malnutrition, and underlying chronic illness.

Because of the compromised nature of these patients, they suffer from a number of HAIs. Urinary tract infections are the most common type of infection reported in LTCFs and can arise due to patient illness or incontinence. Pneumonia, influenza, and lower respiratory tract infections account for significant morbidity and mortality in residents of LTCFs. C. difficile infection is of particular importance in this population as it is the primary cause of diarrhea in nursing homes. Skin, soft tissue, and wound infections are the third most common type of infection in LTCF residents and include infected pressure ulcers and cellulitis, often with group A Streptococci and MRSA. Other infections include viral hepatitis, tuberculosis (TB), and conjunctivitis.

LTCFs face a variety of challenges associated with HAIs. Compared to acute care facilities, nursing homes frequently lack properly trained infection control personnel, and many of these staff members work only part-time on infection control regardless of the size of the facility. Few have a certification in infection control. LTCFs may also have a limited staff, a high staff turnover, problems with funding, and limited information technology (IT) resources, including a computer system that is integrated with diagnostic labs and radiology centers. Nurses in LTCFs must be particularly vigilant in protecting their patients from HAIs.

Enlisting the Help of the Patient and Family

Don’t underestimate the importance of patients and their family members and visitors. With a little education, they can help facilities decrease the spread of infection.

- Educate patients and families on the type of infection diagnosed in the patient, proper hand hygiene, and appropriate precautions, such as contact, droplet, or airborne.

- Keep materials for precautions readily available to visitors, such as gowns, gloves, and masks.

- Encourage all visitors to wash their hands properly before and after visiting with the patient.

- Post instructions on proper handwashing where visitors can see them.

- Keep adequate supplies of hand sanitizer in hallways, near doors, and by elevators and encourage visitors to use them.

Prevention Is The Key=

The Joint Commission includes infection prevention as one of its National Patient Safety Goals in hospitals, behavioral care facilities, and ambulatory care facilities, as well as home health care. Specifically, the Joint Commission emphasizes handwashing as key to infection prevention. Although hand hygiene and transmission precautions are routine in healthcare facilities, a review of evidence-based practice can remind healthcare professionals of the process of and rationale for these procedures.

Proper Hand Hygiene

Handwashing is the single most effective way to prevent the transmission of infection. To understand the effects of handwashing, it is important to consider the environment on human skin. Microorganisms found on the skin are classified as either resident flora, colonizing flora (normal flora), or transient flora. Colonization is the presence of microorganisms in or on a host with growth and multiplication. A person who carries an organism with no clinical signs or symptoms of disease is said to be colonized with that organism. Resident organisms rarely cause infections unless they are introduced into deep tissues through invasive procedures or if the patient is severely immunocompromised. These organisms are usually aerobic, gram positive, and not easily removed by handwashing. Examples include Staphlococcus epidermidis and Corynebacterium spp.

Transient flora are organisms that are recent contaminants that survive only a short time, generally fewer than 24 hours on the skin. They readily cause infection and are most frequently associated with HAIs. These organisms are usually anaerobic, gram negative, and easily removed by handwashing. Examples include streptococci, E. coli, Candida spp., and Klebsiella pneumonia.

An overwhelming amount of literature cites inadequate handwashing in the transfer of organisms such as Staphylococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella in healthcare facilities. Inadequate handwashing also places healthcare workers at risk for viral diseases, such as hepatitis and HIV, and multiple bacterial infections, such as those caused by staphylococci and streptococci.

Various organizations are at work to promote consistent and effective hand hygiene in the healthcare workplace. One agency, the World Health Organization (WHO), created the Five Moments for Hand Hygiene to simplify the timing of handwashing. This handwashing protocol dictates times for hand hygiene within the sequence of patient care to yield the maximum opportunity for patient safety. According to the WHO, the healthcare workers should wash their hands at the following “moments”:

- Before touching a patient

- Before a clean or aseptic procedure is begun

- After exposure to a body fluid

- After touching a patient

- After touching patient surroundings

The theory behind this approach is that if handwashing occurs at the precise time it is needed, transmission of microbes will be halted and patient harm will be prevented. Proponents of the WHO approach hope that the methods taught will stick with healthcare workers and handwashing compliance will increase enough to become an unconscious habit.

The CDC recommends appropriate timing and effective materials for handwashing in the following guidelines for hand hygiene during the delivery of healthcare:

- Hands should be washed with either a nonmicrobial soap and water or, in the following situations, with an antimicrobial soap and water:

- When hands are visibly dirty

- When hands are contaminated with blood or body fluids

- When hands are contaminated with protein-based substances

- When there has been contact with spore-forming bacteria, such as Clostridium difficile (The physical action of handwashing using friction and running water is more likely to remove the spores. Alcohols, chlorhexidine, and other antimicrobial agents used in antiseptic hand rubs have virtually no activity against spores. It should also be noted that alcohol-based hand sanitizers have virtually no effect on reducing the number of genomic copies of Norovirus spp. Hands should be vigorously washed with soap and water when outbreaks of infectious diarrhea or gastrointestinal illness have occurred and Norovirus is the known or suspected agent.)

- When hands are not visibly soiled, or after soil is removed with soap and water, the preferred method of handwashing, or more specifically hand decontamination, is with an alcohol-based hand rub. Hand decontamination with antimicrobial agents (hand asepsis) is indicated for removing or destroying transient organisms. Antibacterial soap and water can also be used. Hands should be decontaminated at the following times:

- Before direct contact with all patients and before donning gloves and performing invasive procedures

- After contact with blood, body fluids, excretions, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, or wound dressings

- After contact with patient intact skin (e.g., when taking blood pressure)

- During patient care, if hands are moving from a contaminated body site to a clean body site

- After contact with inanimate objects and medical equipment near the patient (e.g., bedrails, IV pumps, computer keyboards)

- After removing gloves and other personal protective equipment (PPE)

- Before preparing or eating food

- After contact with one’s own body fluids (e.g., nose blowing, sneezing, using the bathroom)

The use of antiseptic hand rub has brought into question the effectiveness of soap and water. Studies show that when hands of healthcare workers are heavily contaminated with pathogens, alcohol-based antiseptic hand rub prevents transmission of the pathogen much more effectively than plain soap and water handwashing. In a study of the transfer of gram-negative bacilli from the hands of nurses to a piece of catheter material, transfer of the bacilli occurred 2 out of 12 times (17%) when an alcohol-based hand rub was used for hand hygiene, compared to 11 out of 12 times (92%) when plain soap and water were used for hand hygiene. For standard handwashing or hand asepsis, the CDC recommends healthcare workers use alcohol-based products over plain soap or antimicrobial soap, except in the cases listed in the guidelines outlined earlier.

How you wash your hands also matters. Proper handwashing technique must be used to decrease the transmission of infection-causing organisms. Simply rinsing one’s hands with cool water and briefly wiping them dry will not reduce the rate of transmission. To reduce the number of transient organisms, hands must be washed with a sufficient amount of product, with the correct technique, and for a sufficient length of time. The following steps should be taken to ensure proper handwashing:

- When using soap and water:

- Wet hands and apply a sufficient amount of soap (3 ml).

- Rub hands vigorously to create a lather, scrubbing all surfaces of both hands, including backs of hands, wrists, between fingers, and, especially, thumbs and under fingernails. Continue for at least 20 to 30 seconds.

- Rinse hands well under running water.

- Dry hands with a paper towel, and if possible use the paper towel to turn off the faucet on sinks that do not have foot controls or automatic shut-off sensors.

- When using an alcohol-based hand rub:

- Apply the rub to the palm of one hand.

- Rub hands together, wetting all surfaces and focusing on fingernails and fingertips.

- Continue until hands are dry. Drying time should take a minimum of 15–20 seconds if a sufficient amount of rub was applied. If hands are dry in less than 15 seconds, an insufficient amount of product was used.

In addition to maintaining, monitoring, and promoting correct hand hygiene, it is also important for healthcare facilities to perform self-assessments on hand hygiene. The Joint Commission (the accrediting agency for more than 19,000 healthcare organizations) in collaboration with the CDC and other organizations outlined the rationale for self-assessment of handwashing in healthcare facilities:

- To assess the performance of staff members and educate them in real time

- To assess an institution’s level and quality of practice for regulatory or accreditation purposes

- To measure an institution’s performance within high-risk patient populations or units

- To assess the impact of a quality improvement program that increases adherence to hand hygiene guidelines

- To compare the performance of an institution to that of other healthcare facilities

- To investigate an outbreak of infection

- To conduct a research project

- To improve patient and family perception of quality of care

Facilities that assess their effectiveness at prevention can analyze their strengths and weaknesses in prevention efforts and revise their practice to reduce infection rates and thus keep patients safe.