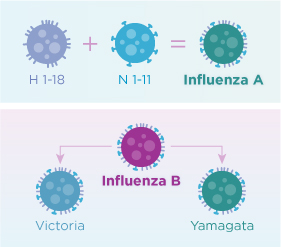

Influenza A (H1N1), Influenza A (H3N2), and one or two influenza B viruses (depending on the vaccine) are included in each year’s influenza vaccine now.

Learn how influenza got started:

The 20th century alone 3 influenza pandemics occurred:

Spanish influenza in 1918 (~50+ million deaths),

Asian influenza in 1957 (two million deaths) and

Hong Kong influenza in 1968 (one million deaths).

FLU Pandemics – The 5 worst FLU outbreaks:

1- “The Russian Flu” -1889

Known as the “Russian Flu,” this influenza outbreak is believed to have begun in St. Petersburg but it soon spread across Europe and the world. It was one of the first epidemics that was covered regularly by the developing daily press. Newspapers wrote about the local spread of the disease and also discussed the situation in other distant European cities thanks to telegraph reports. It is estimated that around 1 million people died of the Russian Flu.

2-“The Spanish Flu” 1918-1919

Influenza was discovered not by a direct study of the disease in humans, but rather from studies on animal diseases. In 1918, J.S. Koen, a veterinarian, observed a disease in pigs which was believed to be the same disease as the now famous “Spanish” influenza pandemic of 1918. If not the most severe pandemic than one of the most severe pandemics in history was the 1918 influenza virus, often called “the Spanish Flu.” The virus infected roughly 500 million people—one-third of the world’s population—and caused 50 million deaths worldwide (double the number of deaths in World War I). In the United States, a quarter of the population caught the virus, 675,000 died, and life expectancy dropped by 12 years. With no vaccine to protect against the virus, people were urged to isolate, quarantine, practice good personal hygiene, and limit social interaction. The World Health Organization declared an outbreak of a new type of influenza A/H1N1 to be a pandemic in June 2009=Swine Flu. Swine flu (H1N1) is a type of viral infection. Swine flu it resembles a respiratory infection that pigs can get. Influenza—more specifically the Spanish flu—left its devastating mark in both world and American history that year. The microscopic killer circled the entire globe in four months, claiming the lives of more than 21 million people. The United States lost 675,000 people to the Spanish flu in 1918-more casualties possibly compared to World War I, the Korean War and the Vietnam War combined not World War 2. Pharmaceutical companies worked around the clock to come up with a vaccine to fight the Spanish flu, but they were too late. The virus disappeared before they could even isolate it. It took 1/3 of the lives on earth.

Until February 2020, the 1918 epidemic was largely overlooked in the teaching of American history, despite the ample documentation at the National Archives and elsewhere of the disease and its devastation.

Over 100-years-old, from 1918, that just months ago seemed quaint and dated now seem oddly prescient. We make these records more widely available in hopes that they contain lessons about what to expect over the coming months and ideas about ways to avoid a repeat and prepare for what may follow. H1N1-RX=VACCINE is the answer!

3-“Asian Flu”1957-1958

In February 1957, a new influenza A (H2N2) virus emerged in East Asia, triggering a pandemic (“Asian Flu”). This H2N2 virus was comprised of three different genes from an H2N2 virus that originated from an avian influenza A virus, including the H2 hemagglutinin and the N2 neuraminidase genes. It was first reported in Singapore in February 1957, Hong Kong in April 1957, and in coastal cities in the United States in summer 1957. The estimated number of deaths was 1.1 million worldwide and 116,000 in the United States.

Asian flu pandemic was a global pandemic of influenza A virus subtype H2N2 that originated in Guizhou in Southern China. The number of excess deaths caused by the pandemic is estimated to be 1–4 million around the world (1957–1958 and probably beyond), making it one of the deadliest pandemics in history.

4-“Hong Kong H3N2 Flu” 1968

The Hong Kong flu, also known as the 1968 flu pandemic, was a flu pandemic that occurred in 1968 and 1969-70 which killed between one and four million people globally. It is among the deadliest pandemics in history, and was caused by an H3N2 strain of the influenza A virus. The virus was descended from H2N2 (which caused the Asian flu pandemic in 1957–1958) through antigenic shift, a genetic process in which genes from multiple subtypes are reassorted to form a new virus. The first recorded instance of the outbreak appeared on 13 July 1968 in British Hong Kong. It has been speculated that the outbreak began in mainland China before it spread to Hong Kong;[10] On 11 July, before the outbreak in the colony was first noted, the Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao reported an outbreak of respiratory illness in Guangdong Province, and the next day, The Times issued a similar report of an epidemic in southeastern China.[13] Later reporting suggested that the flu had spread from the central provinces of Sichuan, Gansu, Shaanxi, and Shanxi, which had experienced epidemics in the spring. However, due to a lack of etiological information on the outbreak and a strained relationship between Chinese health authorities and those in other countries at the time, it cannot be ascertained whether the Hong Kong virus was to blame. The outbreak lasted around six weeks, affecting about 15% of the population (some 500,000 people infected), but the mortality rate was low and the clinical symptoms were mild.

There were two waves of the flu in mainland China, one between July–September in 1968 and the other between June–December in 1970. The reported data were very limited due to the Cultural Revolution, but retrospective analysis of flu activity between 1968 and 1992 shows that flu infection was the most serious in 1968, implying that most areas in China were affected at the time.

The epidemic became widespread in December, involving all 50 states before the end of the year. Outbreaks occurred in colleges and hospitals, in some places the disease attacking upwards of 40% of their populations. Reports of absenteeism among students and nurses grew. Schools in Los Angeles, for example, reported rates ranging from 10 to 25%, compared to a typical 5 or 6%. The Greater New York Hospital Association reported absenteeism of 15 to 20% among staff and urged its members to impose visitor restrictions to safeguard patients. Economic activity was also hampered by high levels of industrial absenteeism.

Peak influenza activity for most states most likely occurred in the latter half of December or early January, but the exact week was impossible to determine due to the holiday season. Activity declined throughout January. Excess pneumonia-influenza mortality passed the epidemic threshold during the first week of December and increased rapidly over the next month, peaking in the first half of January. It took until late March for mortality to return to normal levels. There was no second wave during this season. Following the epidemic of influenza A, outbreaks of influenza B began in late January and continued until late March. Mostly elementary-school children were affected. This influenza B activity fit within the pattern of epidemics every three to six years, but the 1968–1969 flu season became the first documented instance of two major influenza A epidemics to occur in successive seasons. Given the widespread epidemic levels of influenza A activity in 1968–1969, the CDC in June 1969 predicted little more than “sporadic cases” of influenza A in the 1969–1970 season.

The Hong Kong flu was the first known outbreak of the H3N2 strain, but there is serologic evidence of H3N1 infections in the late 19th century. The virus was isolated in Queen Mary Hospital located in Poc Fu Lam on Hong Kong Island of Hong Kong.

The estimates of the total death toll due to Hong Kong flu (from its beginning in July 1968 until the outbreak faded during the winter of 1969–70 vary:

- The World Health Organization and Encyclopaedia Britannica estimated the number of deaths due to Hong Kong flu to be between 1 and 4 million globally.

- The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that, in total, the virus caused the deaths of 1 million people worldwide

However, the death rate from the Hong Kong flu was lower than most other 20th-century pandemics.

5-2009 H1N1 FLU

The 2009 swine flu pandemic, caused by the H1N1/swine flu/influenza virus and declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) from June 2009 to August 2010, was the third recent flu pandemic involving the H1N1 virus (the first being the 1918–1920 Spanish flu pandemic and the second being the 1977 Russian flu). The first identified human case was in La Gloria, Mexico, a rural town in Veracruz. The virus appeared to be a new strain of H1N1 that resulted from a previous triple reassortment of bird, swine, and human flu viruses which further combined with a Eurasian pig flu virus, leading to the term “swine flu” in this pandemic.

In 2009, an H1N1 pandemic infected millions of people worldwide.

Today, you can prevent H1N1 with an annual flu shot. You can treat it with rest, fluids and antiviral medications. The 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic, also known as the swine flu, was the first major influenza outbreak of the 21st century.

Swine flu first appeared in Mexico and the United States in March and April 2009 and has swept the globe with unprecedented speed as a result of airline travel.

On June 11, 2009, the World Health Organization raised its pandemic level to the highest level, Phase 6, indicating widespread community transmission on at least two continents. The 2009 H1N1 virus contains a unique combination of gene segments from human, swine and avian influenza. This new H1N1 virus contained a unique combination of influenza genes not previously identified in animals or people. This virus was designated as influenza A (H1N1) virus. Ten years later work continued to better understand influenza, prevent disease, and prepare for the next pandemic.

Influenza may also affect other wild life which are horses, chickens and birds along with the pigs. In late 1917, military pathologists reported the onset of a new disease with high mortality that they later recognized as the flu. The overcrowded camp and hospital — which treated thousands of victims of chemical attacks and other casualties of war — was an ideal site for the spreading of a respiratory virus; 100,000 soldiers were in transit every day. It also was home to a live piggery, and poultry were regularly brought in for food supplies from surrounding villages. Oxford and his team postulated that a significant precursor virus, harbored in birds, mutated so it could migrate to pigs that were kept near the front.

Influenza A virus subtype H5N1, also known as A(H5N1) or simply H5N1, is a subtype of the influenza A virus which can cause illness in humans and many other animal species. A bird-adapted strain of H5N1, called HPAI A(H5N1) for highly pathogenic avian influenza virus of type A of subtype H5N1, is the highly pathogenic causative agent of H5N1 flu, commonly known as avian influenza (“bird flu“). It is enzootic (maintained in the population) in many bird populations, especially in Southeast Asia.

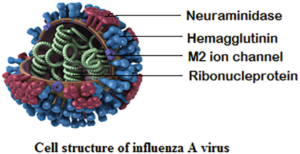

CDC Centers for Disease Control blog site states, “There are four types of influenza viruses: A, B, C and D. Human influenza A and B viruses cause seasonal epidemics of disease almost every winter in the United States. The emergence of a new and very different influenza A virus to infect people can cause an influenza pandemic. Influenza type C infections generally cause a mild respiratory illness and are not thought to cause epidemics. Influenza D viruses primarily affect cattle and are not known to infect or cause illness in people.

Influenza A viruses can be further broken down into different strains. Current subtypes of influenza A viruses found in people are influenza A (H1N1) and influenza A (H3N2) viruses. In the spring of 2009, a new influenza A (H1N1) virus (CDC 2009 H1N1 Flu website) emerged to cause illness in people. This virus was very different from the human influenza A (H1N1) viruses circulating at that time. The new virus caused the first influenza pandemic in more than 40 years. That virus (often called “2009 H1N1”) has now replaced the H1N1 virus that was previously circulating in humans.

Influenza B viruses are not divided into subtypes, but can be further broken down into lineages and strains. Currently circulating influenza B viruses belong to one of two lineages: B/Yamagata and B/Victoria. Unlike type A flu viruses, type B flu is found only in humans. Type B flu may cause a less severe reaction than type A flu virus, but occasionally, type B flu can still be extremely harmful. Influenza type B viruses are not classified by subtype. However, influenza B viruses do not cause pandemics.

CDC follows an internationally accepted naming convention for influenza viruses. This convention was accepted by WHO in 1979 and published in February 1980 in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 58(4):585-591 (1980) (see A revision of the system of nomenclature for influenza viruses: a WHO Memorandum[854 KB, 7 pages]). The approach uses the following components:

- The antigenic type (e.g., A, B, C)

- The host of origin (e.g., swine, equine, chicken, etc. For human-origin viruses, no host of origin designation is given.)

- Geographical origin (e.g., Denver, Taiwan, etc.)

- Strain number (e.g., 15, 7, etc.)

- Year of isolation (e.g., 57, 2009, etc.)

- For influenza A viruses, the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase antigen description in parentheses (e.g., (H1N1), (H5N1)

For example:

- A/duck/Alberta/35/76 (H1N1) for a virus from duck origin

- A/Perth/16/2009 (H3N2) for a virus from human origin

Getting a flu vaccine can protect against flu viruses that are the same or related to the viruses in the vaccine. Information about this season’s vaccine can be found at Preventing Seasonal Flu with Vaccination. The seasonal flu vaccine does not protect against influenza C viruses. Additionally, flu vaccines will NOT protect against infection and illness caused by other viruses that also can cause influenza-like symptoms. There are many other non-flu viruses that can result in influenza-like illness (ILI) that spread during flu season. If people got vaccines high odds there would be less influenza spreading throughout the country you live in or globally with travelers for both pleasure and business.

- Flu vaccines have been updated to better match circulating viruses [the B/Victoria component was changed and the influenza A(H3N2) component was updated].

- For the 2018-2019 season, the nasal spray flu vaccine (live attenuated influenza vaccine or “LAIV”) is again a recommended option for influenza vaccination of persons for whom it is otherwise appropriate. The nasal spray is approved for use in non-pregnant individuals, 2 to 49 years old. There is a precaution against the use of LAIV for people with certain underlying medical conditions. All LAIV will be quadrivalent (four-component).”

PMC U.S. National Library of Medicine (National Institutes of Health) states, “the announcement in 2005 that a virus causing fatal influenza during the great influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 had been sequenced in its entirety [1], in the laboratory of co-author JKT, has prompted renewed interest in the 1918 virus. The ongoing H5N1 avian influenza epizootic, and the possibility that it might also cause a pandemic [2], increase the importance of understanding what happened in 1918. However, in reviewing the scientific approach to unlocking an old puzzle, it is important to note that the sequencing of the 1918 virus took place after more than century of exhaustive and sometimes disheartening efforts to discover the cause of influenza (Figure 1). Indeed, the influenza search not only pre-dated the great pandemic of 1918, but also attracted the efforts of some of the greatest researchers of the 19th and 20th centuries. Along the way, the new fields of bacteriology and virology were advanced, and a productive marriage between microbiology, epidemiology and experimental science began. In describing here the 10-year effort (1995–2005) to sequence the genome of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus, we attempt also to place it within this important historical perspective.”

Influenza virus C is a genus in the virus family Orthomyxoviridae, which includes the viruses that cause influenza. Nearly all adults have been infected with influenza C virus, which causes mild upper respiratory infections. Cold-like symptoms are associated with the virus including fever (38-40ᵒC=100.4 to 104F), dry cough, rhinorrhea (nasal discharge), headache, muscle pain, and achiness. The virus may lead to more severe infections such as bronchitis and pneumonia. Lower tract complications are rare. There is no vaccine against influenza C virus.

The species in this genus is called Influenza C virus. Influenza C viruses are known to infect humans and pigs.

Influenza D viruses primarily affect cattle and are not known to infect or cause illness in people.