When people languish on a wait-list for a kidney transplant, they may start to consider a desperate measure: Traveling to a country where they can buy a donor kidney on the black market.

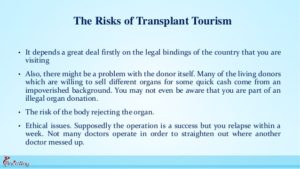

But beyond the legal and ethical pitfalls, experts say, the health risks are not worth it.

Most countries ban the practice, sometimes called “transplant tourism,” and it has been widely condemned on ethical ground. Now a new study highlights another issue: People who buy a donor kidney simply do not fare as well.

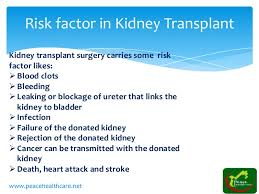

Researchers in Bahrain found that people who traveled abroad to buy a kidney — to countries like the Philippines, India, Pakistan, China and Iran — sometimes developed serious infections.

Those infections included the liver diseases hepatitis B and C, as well as cytomegalovirus, which can be life-threatening to transplant recipients, the investigators said.

Also, people who bought donor kidneys also faced higher rates of surgical complications and organ rejection, versus those who received a legal transplant in their home country.

Dr. Amgad El Agroudy, of Arabian Gulf University, was to present the findings Friday at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN), in San Diego.

It’s not clear how common it is for U.S. patients to take a chance on traveling abroad to buy a black-market kidney, according to Dr. Gabriel Danovitch, director of kidney transplantation at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We really have no way of knowing what the numbers are,” said Danovitch, who was not involved in the study.

“But,” he added, “my sense is that the numbers are fairly small, as the dangers of transplant tourism are becoming more and more clear.”

Why is it a risky proposition? According to Danovitch, there are a few broad reasons: The paid organ donors may not be properly screened, and the recipients may not be good candidates for a transplant, to name two.

“In a paid system, the prime focus is on making money,” Danovitch said. “Centers that are willing to do these don’t really care what happens to the donors or recipients after the transplant.”

For people with advanced chronic kidney failure, the treatment options are dialysis or a transplant. But there are not enough donor organs to meet the need. In the United States, nearly one million people have end-stage kidney disease, and there are roughly 102,000 people on the waiting list for a transplant, according to the National Kidney Foundation.

Kidney transplants can come from a living or deceased donor, but living-donor transplants are more likely to be successful, according to U.S. health officials.

It doesn’t take long to get tired of spending 12 hours a week on hemodialysis, or even more time on peritoneal dialysis (PD) —not to mention complications like line infections and access problems. But a new, healthy kidney would put an end to all that. A transplant sounds like it would be well worth the risk of surgery and the trouble of taking anti-rejection medicines, and Medicare statistics show that it actually costs less in the long run than continued dialysis. When can you check into the hospital, you ask?

Unfortunately over 80,000 people in the United States are already waiting for a new kidney and in 2008 only 16,517 got one. Maybe you don’t have a compatible donor in your family, or you’ve been told that you are “not a transplant candidate” for one of several reasons. You’re a resourceful person who knows that persistence pays off, and you start looking for ways to shorten the wait or get around the rules that say you don’t qualify for a transplant. Kidneys from living donors are almost always preferable to those from recently deceased donors. If you don’t have a friend or family member willing to donate, what about getting one where the laws against buying an organ are less strictly enforced? Medical tourism is booming these days. Maybe you know somebody who had surgery overseas, either to avoid a waiting list or just because the price is lower there. The same international pharmaceutical countries produce medicines for everybody these days, so how big a difference can there be? Nephrologists in the US say it’s a common story: a dialysis patient misses treatments or appointments for a few days or several weeks, then comes to their office asking for refills on anti-rejection medicines…with pill bottles labeled in Urdu, Chinese or Farsi as well as in English. Did they get a good deal or what? Unfortunately this may not be the bargain people hoped for.

At UCLA Jagbir Gill, MD, and associates studied 33 patients who had received transplants overseas, and found they had much worse results than patients who received transplants in this country. Screening of paid kidney donors was less thorough, with problems like hepatitis overlooked. Early organ rejection was twice as common and infections frequent; Dr. Gill recalls patients who went “directly from the airport to the emergency room” due to severe infections or transplant failure.

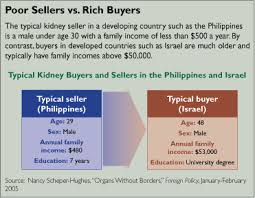

In a similar study in Canada, where waiting periods for transplants are even longer, experiences were similar. Jeffrey Zaltzman, MD, reports infections common in the countries where the transplant was done were a big problem in medical tourists. One 78-year-old gentleman returned from Pakistan with a surgical wound that reopened spontaneously; he died a few weeks later of cardiovascular problems that might have disqualified him for a transplant at home. The cost to paid organ donors can be even greater. Poor people who sell a kidney, sometimes for as little as $800 according to the World Health Organization, face health problems like hypertension and worsening of their own kidney functions—provided, of course, that their surgery goes well. Since most live in countries where even blood pressure checks are rare, complications that develop after they leave the hospital may go undetected until it is too late for the patient. Donors in the United States frequently can have kidneys removed with very small incisions. Third World donors, however, generally end up with wounds up to 14 inches long that may take months to heal, making them unable to do the manual labor most depend on. Chronic pain and disability are common, points out Nancy Scheper-Hughes, who has extensively studied and reported on transplant practices from Brazil to China. And reports of organs coming from executed prisoners in China are even more worrisome. Details of where donors come from and which hospitals and doctors will do the surgery are rarely available to “clients” and their families ahead of time. While paying a donor for an organ is illegal everywhere except Iran, “international transplant coordinators” have no laws banning what they do—bringing clients together with hospitals in other countries. And as the WHO’s Dr. Luc Noel points out, “None of the brokers ever mention the costs—long-term health issues, chronic pain, inability to perform manual labor—that are borne by these poor organ vendors.”

SO THINK TWICE BEFORE FALLING FOR TRANSPLANT TOURISM. HIGH PROBABILITY YOU WON’T LIKE THE RESULTS!