What is Lou Gehrig’s Disease (also called ALS or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) exactly?

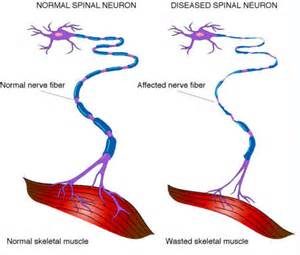

ALS, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and the spinal cord. A-myo-trophic comes from the Greek language. “A” means no. “Myo” refers to muscle, and “Trophic” means nourishment – “No muscle nourishment.” When a muscle has no nourishment, it “atrophies” or wastes away. “Lateral” identifies the areas in a person’s spinal cord where portions of the nerve cells that signal and control the muscles are located. As this area degenerates it leads to scarring or hardening (“sclerosis”) in the region.

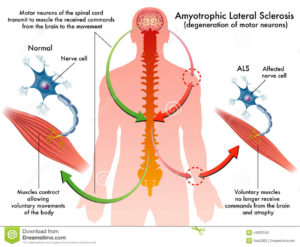

Motor neurons reach from the brain to the spinal cord and from the spinal cord to the muscles throughout the body. The progressive degeneration of the motor neurons in ALS eventually leads to their demise. When the motor neurons die, the ability of the brain to initiate and control muscle movement is lost. With voluntary muscle action progressively affected, people may lose the ability to speak, eat, move and breathe. The motor nerves that are affected when you have ALS are the motor neurons that provide voluntary movements and muscle control. Examples of voluntary movements are making the effort to reach for a smart phone or step off a curb. These actions are controlled by the muscles in the arms and legs. Motor neurons are nerve cells located in the brain, brain stem, and spinal cord that serve as controlling units and vital communication links between the nervous system and the voluntary muscles of the body. Messages from motor neurons in the brain called upper motor neurons are transmitted to motor neurons in the spinal cord which are lower motor neurons and from them to particular muscles. The problem with ACL, both the upper motor niurons and the ower motor niurons degenerate or die which causes stoppage of sending messages to muscles. Unable to function, the muscles gradually weaken, waste away (atrophy), and have very fine twitches (called fasciculations). Eventually, the ability of the brain to start voluntary movement with messages is unable to work anymore.

Symptoms:

The onset of ALS may be so subtle that the symptoms are overlooked. The earliest symptoms may include fasciculations, cramps, tight and stiff muscles (spasticity), muscle weakness affecting an arm or a leg, slurred and nasal speech, or difficulty chewing or swallowing. These general complaints then develop into more obvious weakness or atrophy that may cause a physician to suspect ALS. Regardless of the part of the body first affected by the disease, muscle weakness and atrophy spread to other parts of the body as the disease progresses.

The parts of the body showing early symptoms of ALS depend on which muscles in the body are affected. Many individuals first see the effects of the disease in a hand or arm as they experience difficulty with simple tasks requiring manual dexterity such as buttoning a shirt, writing, or turning a key in a lock. In other cases, symptoms initially affect one of the legs, and people experience awkwardness when walking or running or they notice that they are tripping or stumbling more often.

There are two different types of ALS, 1 sporadic and 2 familial.

Sporadic which is the most common form of the disease in the U.S., is 90 – 95 percent of all cases. It may affect anyone, anywhere.

Familial ALS (FALS) accounts for 5 to 10 percent of all cases in the U.S. Familial ALS means the disease is inherited. In those families, there is a 50% chance each offspring will inherit the gene mutation and may develop the disease. French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot discovered the disease in 1869.

Causes of ALS:

The cause of ALS is not known, and scientists do not yet know why ALS strikes some people and not others. An important step toward answering this question was made in 1993 when scientists supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) discovered that mutations in the gene that produces the SOD1 enzyme were associated with some cases of familial ALS.

ALS usually strikes people between the ages of 40 and 70, and approximately 20,000 Americans can have the disease at any given time (although this number fluctuates). For unknown reasons, military veterans are approximately twice as likely to be diagnosed with the disease than the general public. Notable individuals who have been diagnosed with ALS include baseball great Lou Gehrig, Hall of Fame pitcher Jim “Catfish” Hunter, Toto bassist Mike Porcaro, Senator Jacob Javits, actor David Niven, “Sesame Street” creator Jon Stone, boxing champion Ezzard Charles, NBA Hall of Fame basketball player George Yardley, golf caddie Bruce Edwards, , musician Lead Belly (Huddie Ledbetter), photographer Eddie Adams, entertainer Dennis Day, jazz musician Charles Mingus, former vice president of the United States Henry A. Wallace, U.S. Army General Maxwell Taylor, and NFL football players Steve Gleason, O.J. Brigance and Tim Shaw.

Who gets ALS?

More than 12,000 people in the U.S. have a definite diagnosis of ALS, for a prevalence of 3.9 cases per 100,000 persons in the U.S. general population, according to a report on data from the National ALS Registry. ALS is one of the most common neuromuscular diseases worldwide, and people of all races and ethnic backgrounds are affected. ALS is more common among white males, non-Hispanics, and persons aged 60–69 years, but younger and older people also can develop the disease. Men are affected more often than women.

In 90 to 95 percent of all ALS cases, the disease occurs apparently at random with no clearly associated risk factors. Individuals with this sporadic form of the disease do not have a family history of ALS, and their family members are not considered to be at increased risk for developing it.

About 5 to 10 percent of all ALS cases are inherited. The familial form of ALS usually results from a pattern of inheritance that requires only one parent to carry the gene responsible for the disease. Mutations in more than a dozen genes have been found to cause familial ALS.

About one-third of all familial cases (and a small percentage of sporadic cases) result from a defect in a gene known as “chromosome 9 open reading frame 72,” or C9orf72. The function of this gene is still unknown. Another 20 percent of familial cases result from mutations in the gene that encodes the enzyme copper-zinc superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1).

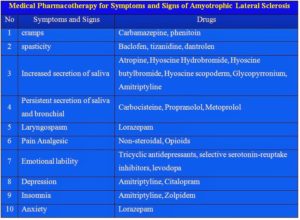

Treatments to this disease:

Recent years have brought a wealth of new scientific understanding regarding the physiology of this disease. There is currently one FDA approved drug, riluzole, that modestly slows the progression of ALS in some people. Although there is not yet a cure or treatment that halts or reverses ALS, scientists have made significant progress in learning more about this disease. In addition, people with ALS may experience a better quality of life in living with the disease by participating in support groups and attending an ALS Association Certified Treatment Center of Excellence or a Recognized Treatment Center. Such Centers provide a national standard of best-practice multidisciplinary care to help manage the symptoms of the disease and assist people living with ALS to maintain as much independence as possible for as long as possible. According to the American Academy of Neurology’s Practice Paramater Update, studies have shown that participation in a multidisciplinary ALS clinic may prolong survival and improve quality of life.

To find a Center near you, visit http://www.alsa.org/community/certified-centers/.

Remember there is no cure yet that has been found for ALS. However, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first drug treatment for the disease—riluzole (Rilutek)—in 1995. Riluzole is believed to reduce damage to motor neurons by decreasing the release of glutamate. Clinical trials with ALS patients showed that riluzole prolongs survival by several months, mainly in those with difficulty swallowing. The drug also extends the time before an individual needs ventilation support. Riluzole does not reverse the damage already done to motor neurons, and persons taking the drug must be monitored for liver damage and other possible side effects. However, this first disease-specific therapy offers hope that the progression of ALS may one day be slowed by new medications or combinations of drugs.