The purpose of this article is to help broaden the public in knowing about HAIs including how their family or friend should be cared for when in a hospital with what they can do when visiting a loved one in a health facility for both the patient’s and visitor’s benefit.

History of HAIs

Let us start with some history. In England in the 1830s, the term hospitalism was coined by Sir James Simpson to describe HAIs. In those days, it was believed that infection was spread because of inadequate ventilation and stagnant air. To prevent infection, windows were opened, and whenever possible care was taken to prevent overcrowding of hospital rooms. Little was known about microbes and their pathogenicity, and consequently little was done about personal hygiene. In Victorian society, the idea of one’s personal hygiene being connected to infection was taken personally and was met with great resistance.

Despite the efforts of medical personnel, many patients died of overwhelming sepsis following preventable infections. In the late 1860s after much persistence, Joseph Lister, a British surgeon, introduced the concept of antisepsis, which significantly decreased death from postoperative infection. After penicillin was introduced in 1941, postsurgical infection rates and deaths from postsurgical pneumonia were both dramatically decreased.

Today, modern medicine has brought a more thorough understanding of pathogens and the epidemiology of the diseases they cause. Unfortunately, in spite of the vast amounts of medical advances that have occurred over the years, the healthcare industry is still faced with the enormous task of preventing and reducing the risk of HAIs.

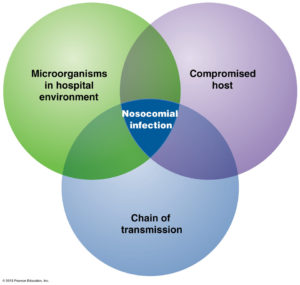

Today HAIs are defined as nosocomial infections which are infections that are acquired in hospitals and other healthcare facilities (like a nursing home or sub-acute rehab facility). To be classified as a nosocomial infection the patient must have been admitted for reasons other than an infection. He or she must also have shown no signs of active or incubating infection upon admission.

On average, nosocomial patients stay in the hospital 2.5 times longer than patients without infection. An estimated 40 percent of nosocomial infections are caused by poor hand hygiene (WHO). Hospital staff can significantly reduce the number of cases with regular hand washing. They should also wear protective garments and gloves when working with patients.

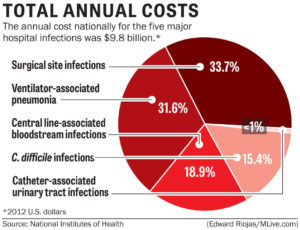

Invasive procedures increase the risk of nosocomial infections. Noninvasive procedures are recommended when possible. Most nosocomial infections are due to bacteria. Since antibiotics are frequently used within hospitals, the types of bacteria and their resistance to antibiotics is different than bacteria outside of the hospital. Nosocomial infections can be serious and difficult to treat, especially if it’s a multi-resistant bacteria.

How do infections even occur?

Harmful microbes are all around us, and although infection poses a threat to everyone, certain people are more at a potential of infection. For example, people in healthcare facilities are more at risk than those in the community simply because they are exposed to others who are infected with disease-causing organisms. These people are exposed to so many other peoples germs and bacteria as opposed to a private home simply puts you at potential for picking up them if not proper prevention is carried out by all that come in contact with you, starting simply with hand washing by the patient and those that see the patient (medical staff to visitors).

Even more at risk are special populations or conditions of patients, such as those with compromised immune systems, those who have undergone recent surgery, those with poor nutritional status, and those with open wounds. Patients undergoing certain medical procedures, such as intubations and central lines, are also at increased risk. Medical devices also carry a risk of infection. Urinary catheters, central lines, mechanical ventilation equipment, and surgical drains all put patients at risk for infection. Any foreign object in the body or any unnatural opening of the body (Ex. surgical wounds or trauma wounds) puts that individual at risk for local infection to that area and if left untreated goes to general infection (temp greater than 100.5 or 101 F). We will go into more detail on risk factors tomorrow in Part 2.

Further, certain medications and various chemotherapies weaken patients’ immune systems, leaving patients more vulnerable to infection. The length of time spent in a healthcare facility also affects the risk of infection: The longer the stay, the longer that person is at potential for exposure of bacteria. A person in a hospital versus in a home puts greater risk for that person’s chances of acquiring a HAI since there is more bacteria and germs exposure in a hospital compared to a home due to the population. Over 25 years ago and further back the doctors kept patients in the hospital longer than needed; they were thinking this was the best care for the patient but now it’s get the patient out as soon as possible when clearance from the MD’s for discharge is reached. The logic behind this is to get that patient back at home exposed to less bacteria or germs where they can reach their optimal level of functioning since they no longer need a hospital care but follow up with their MD at their office.

How does infection travel from one object to another or even person to person?

The most common method of transmission is by direct contact with an infectious microorganism. Sputum, blood, and feces are common vehicles for microbe transmission. Healthcare workers and patients spread microbes via droplets generated by talking, sneezing, or coughing. Small particles of evaporated droplets (droplet nuclei) and dust particles carry microorganisms and spread infection over long distances.

Infection can also be spread through inanimate objects known as fomites; which are any object or substance capable of carrying infectious organisms, such as germs or parasites, and hence transferring them from one individual to another. Fomites can be skin cells, hair, clothing, and bedding which are common hospital sources of contamination including improperly sterilized medical equipment that is used on more than one patient. Healthcare workers who move from patient to patient carry infectious organisms on their clothes, stethoscopes, and phones. Other modes of transmission include the spread of infectious agents through food and water or through vectors, such as mosquitoes, flies, and rats.

Though hospitals throughout America have this problem to face but so do hospitals elsewhere; it’s a worldwide problem. Know these facilities in most places have developed infection control people who continuously make policies/procedures in their facilities to prevent the spread of infection through all routes with the knowledge we know today as opposed to 25 years ago and further back regarding infection spreading in the hospital.

Turn into Part 2 and read about what puts people at risk for health acquired infections HAIs.