What are the signs and symptoms (s/s) of this disease?

The early signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease that are often overlooked by both patients and doctors because the symptoms are subtle and the progression of the disease is typically slow. S/S of parkinson’s disease are:

Parkinson’s disease does not affect everyone the same way. In some people the disease progresses quickly, in others it does not. Although some people become severely disabled, others experience only minor motor disruptions. Tremor is the major symptom for some patients, while for others tremor is only a minor complaint and different symptoms are more troublesome.

The Motor function symptoms associated with Parkinson’s Disease:

- The tremors associated with Parkinson’s disease has a characteristic appearance. Typically, the tremor takes the form of a rhythmic back-and-forth motion of the thumb and forefinger at three beats per second. This is sometimes called “pill rolling.” Tremor usually begins in a hand, although sometimes a foot or the jaw is affected first. It is most obvious when the hand is at rest or when a person is under stress. In three out of four patients, the tremor may affect only one part or side of the body, especially during the early stages of the disease. Later it may become more general. Tremor is rarely disabling and it usually disappears during sleep or improves with intentional movement.

- Rigidity, or a resistance to movement, affects most parkinsonian patients. A major principle of body movement is that all muscles have an opposing muscle. Movement is possible not just because one muscle becomes more active, but because the opposing muscle relaxes. In Parkinson’s disease, rigidity comes about when, in response to signals from the brain, the delicate balance of opposing muscles is disturbed. The muscles remain constantly tensed and contracted so that the person aches or feels stiff or weak. The rigidity becomes obvious when another person tries to move the patient’s arm, which will move only in ratchet-like or short, jerky movements known as “cogwheel” rigidity.

- Bradykinesia, or the slowing down and loss of spontaneous and automatic movement, is particularly frustrating because it is unpredictable. One moment the patient can move easily. The next moment he or she may need help. This may well be the most disabling and distressing symptom of the disease because the patient cannot rapidly perform routine movements. Activities once performed quickly and easily — such as washing or dressing — may take several hours.

- Postural instability, or impaired balance and coordination, causes patients to develop a forward or backward lean and to fall easily. When bumped from the front or when starting to walk, patients with a backward lean have a tendency to step backwards, which is known as retropulsion. Postural instability can cause patients to have a stooped posture in which the head is bowed and the shoulders are drooped.

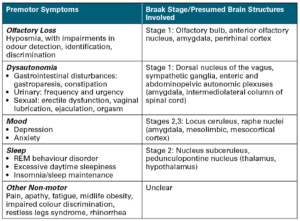

The Non-Motor function symptoms that are often associated with Parkinson’s Disease include:

-Cognitive impairment –Dementia –Psychosis –Depression –Fatigue -Sleep disturbances -Constipation -Sexual dysfunction -Vision disturbances.

As the disease progresses, walking may be affected. Patients may halt in mid-stride and “freeze” in place, possibly even toppling over. Patients may walk with a series of quick, small steps as if hurrying forward to keep balance. This is known as festination.

A detailed overview of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale that is used by doctors to follow the course of disease progression and evaluate the extent of impairment and disability.

Abstract

The Movement Disorder Society Task Force for Rating Scales for Parkinson’s Disease prepared a critique of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). Strengths of the UPDRS include its wide utilization, its application across the clinical spectrum of PD, its nearly comprehensive coverage of motor symptoms, and its clinimetric properties, including reliability and validity. Weaknesses include several ambiguities in the written text, inadequate instructions for raters, some metric flaws, and the absence of screening questions on several important non-motor aspects of PD. The Task Force recommends that the MDS sponsor the development of a new version of the UPDRS and encourage efforts to establish its clinimetric properties, especially addressing the need to define a Minimal Clinically Relevant Difference and a Minimal Clinically Relevant Incremental Difference, as well as testing its correlation with the current UPDRS. If developed, the new scale should be culturally unbiased and be tested in different racial, gender, and age-groups. Future goals should include the definition of UPDRS scores with confidence intervals that correlate with clinically pertinent designations, “minimal,” “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe” PD. Whereas the presence of non-motor components of PD can be identified with screening questions, a new version of the UPDRS should include an official appendix that includes other, more detailed, and optionally used scales to determine severity of these impairments.

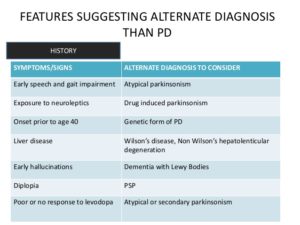

How Parkinson’s disease is diagnosed:

There isn’t a specific test to diagnose Parkinson’s disease; it is based on factors such as signs/symptoms, patient history, physical examination, and a thorough neurological evaluation.

A doctor trained in nervous system conditions (neurologist) will diagnose Parkinson’s disease based on your medical history, a review of your signs and symptoms, and a neurological and physical examination.

Your doctor may suggest a specific single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) scan called a dopamine transporter (DAT) scan. Although this can help support the suspicion that you have Parkinson’s disease, it is your symptoms and neurological examination that ultimately determine the correct diagnosis. Most people do not require a DAT scan.

Furthermore, making the diagnosis is even more difficult since there are currently no blood or lab tests available to diagnose the disease. Your health care provider may order lab tests, such as blood tests, to rule out other conditions that may be causing your symptoms. Some tests, such as a CT Scan (computed tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and PET Scans may be used to rule out other disorders that cause similar symptoms. Imaging tests aren’t particularly helpful for diagnosing Parkinson’s disease. Given these circumstances, a doctor may need to observe the patient over time to recognize signs of tremor and rigidity, and pair them with other characteristic symptoms.

The doctor will also compile a comprehensive history of the patient’s symptoms, activity, medications, other medical problems, and exposures to toxic chemicals. This will likely be followed up with a rigorous physical exam with concentration on the functions of the brain and nervous system. Tests are conducted on the patient’s reflexes, coordination, muscle strength, and mental function. Making a precise diagnosis is essential for prescribing the correct treatment regimen. The treatment decisions made early in the illness can have profound implications on the long-term success of treatment.

Recommended Related to Parkinson’s

Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Parkinson’s Disease:

Since you’ve recently been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, ask your doctor these questions at your next visit. 1.What stage is my illness in now?

2. How quickly do you think my disease will progress?

3. How will Parkinson’s disease affect my work?

4. What physical changes can I expect?

5. Will I be able to keep up the activities, hobbies, and sports I do now?

6. What treatments do you suggest now?

7.Will that change as the disease progresses?

8. What are the side effects of medication?…

Because the diagnosis is based on the doctor’s exam of the patient, it is very important that the doctor be experienced in evaluating and diagnosing patients with Parkinson’s disease. If Parkinson’s disease is suspected, you should see a specialist, preferably a movement disorders trained neurologist.